Vocational baccalaureate system struggles to grow

Getting a qualification that allows you to study after an apprenticeship is a hallmark of Switzerland’s vocational training system, but the number of young people taking this route is stagnating. Why?

It used to be the case that you either did an apprenticeship or studied at university in Switzerland. But the vocational baccalaureate, introduced in the 1990s, enabled apprentices to go on to study for a Bachelors or Masters degree at one of the country’s Universities of Applied Sciences, where the emphasis is on practical applications and industry.

Since then international studiesExternal link – and domestic expertsExternal link – have singled out this permeability in the Swiss training system as one of the keys to the country’s success in keeping youth unemployment low, as well as its competitiveness and innovation.

More

Why Switzerland’s dual-track education system is unique

Most countries with an emphasis on vocational training provide some way into higher education afterwards. “But the Swiss vocational baccalaureate stands out because it is not a small, exceptional path, but a large bridge: two-thirds of all Swiss youngsters attend apprenticeship programmes, and around one-quarter of these also earn a vocational baccalaureate,” explained Jürg SchweriExternal link, a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (SFIVETExternal link).

An electrician can therefore easily go on to study electrical engineering at a University of Applied Sciences (UAS) – where students are mostly qualified apprentices. (An extra exam is needed to attend an academic university).

This flexible approach is designed to ensure a highly qualified workforce for the modern economy, Schweri said.

The emphasis on VET means that only around 25% of young people attend academic university in Switzerland, which is a low proportion compared with other OECD countries such as Australia and the United States.

No growth

But a recent SFIVET study has found that uptake of the vocational baccalaureate (VB) is stagnating, having increased just 7% over the past eight years. Some 13% of apprentices take the qualification during their vocational training and around 10% opt for a year-long course afterwards (this option is becoming more popular and mainly accounts for the 7% rise). It is the first model that is tailing off, statistics show, because it can be difficult for apprentices to juggle training and school.

“The schedule is tough for apprentices,” Schweri said.

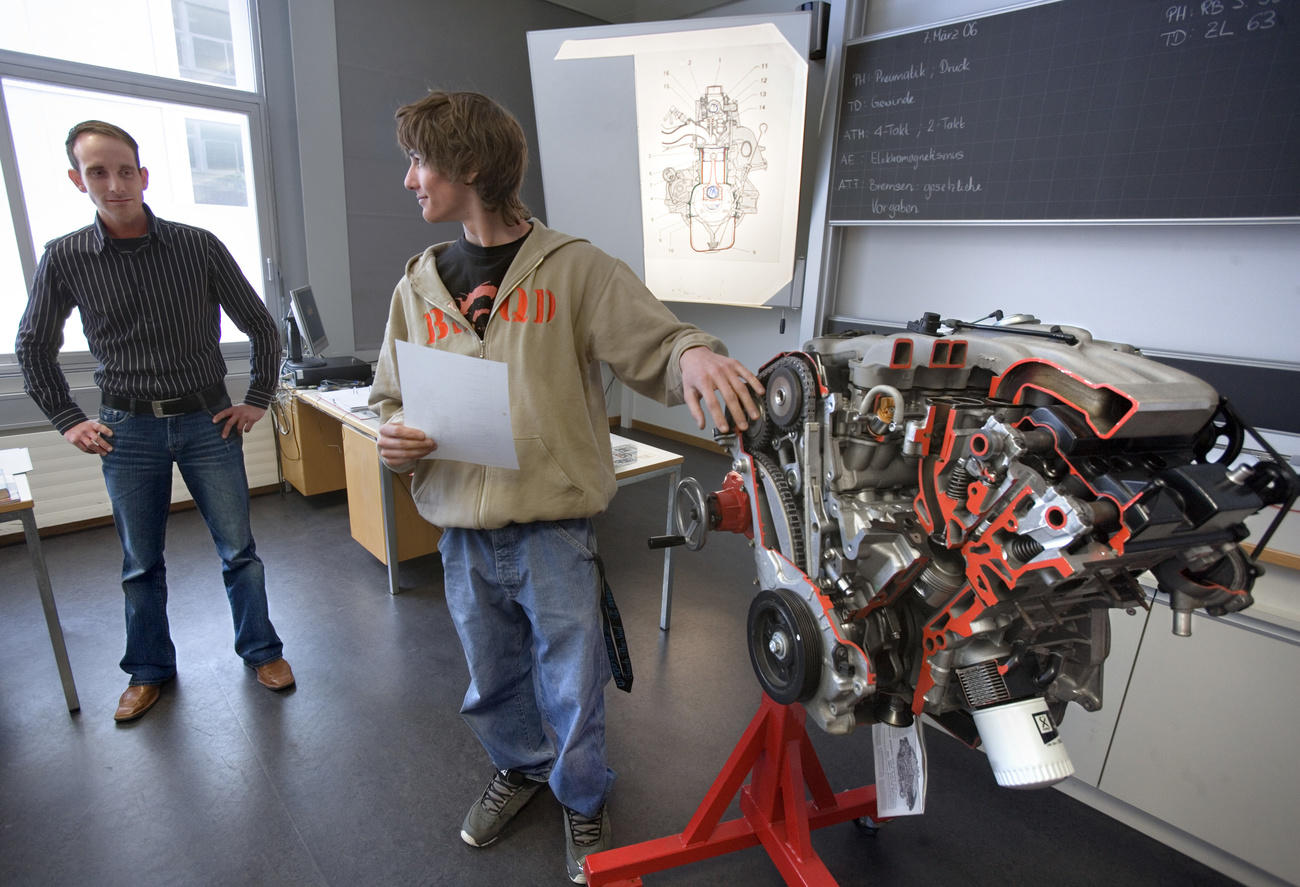

Under Switzerland’s dual-track apprenticeship systemExternal link, young people combine on-the-job training with lessons in a vocational school during their apprenticeships. Vocational baccalaureate lessons come on top of this, meaning an apprentice must be very motivated and well-organised.

Plus, some firms don’t like their apprentices to be absent too much.

In addition, some parents – who are key in influencing their kids’ career choices which are made early, around age 14 or 15 – are still not aware of the vocational baccalaureate, he added.

More

Are 14-year-olds ready to make a career choice?

Stamina, being challenged

A young dental assistant who opted for the vocational baccalaureate said in a recent online SFVET conference that it was important to “keep your career goal in mind” and find a balance between work and play when pursuing the certification.

Young people need and want to be challenged, added Oskar Egli, head of vocational training at HunkelerExternal link, a paper processing firm where all apprentice polytechnical specialists (involved in high-tech development/production) do the vocational baccalaureate in parallel to their apprenticeships. “Otherwise these young people will simply go to baccalaureate schools [the schools that lead to regular university],” he told the conference.

Indeed, the qualification is generally taken by apprentices in a few, more academically demanding professions – three-quarters of those who participate are in just eight professions, the most popular being electronics engineer, laboratory worker and design engineer.

The success rate is around two-thirds for the parallel qualification and four-fifths for the post-apprenticeship model.

Of those who pass the VB, two-thirds go on to higher education, with most opting for a university of applied sciences, the study found. A third changed career altogether.

Is the VB needed?

Could it be that the Swiss VET system already offers young people enough perspective on the labour market without the vocational baccalaureate? There are already higher education programmes for apprentices that do not require the VB, such as the Advanced Federal Diploma of Higher EducationExternal link, which involves the acquisition of managerial and deeper practical skills.

This is likely part of the explanation for the stagnation, according to Schweri.

But that’s not to say there isn’t a place for it. A Hunkeler apprentice said at the online conference that his apprenticeship gave him “the experience in the company” but that the VB secured him the possibility of studying later on at a University of Applied Sciences, which adds more theory into the practical side.

“The vocational baccalaureate will become even more important if the economy continues to ask for ever more highly-educated workers,” Schweri pointed out.

There is a debate in Switzerland over whether more young people should attend baccalaureate schools and go to university. But so far Switzerland has kept to its ‘vocational training first’ approach.

“[This] means that the pool of students in the different types of universities has to increase via the VB path,” Schweri said.

In the meantime, the vocational baccalaureate could be boosted by several measures, such as splitting the work between during and after the apprenticeship. “We should also focus on pedagogical issues and support for learners, as there is a significant group of apprentices that starts these courses and then drops out,” Schweri said.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.