Aussie adoptee gains Swiss citizenship at 54 thanks to old envelope

For decades, Swiss authorities wrongly denied her citizenship. But Cate Riley, daughter of Swiss parents and adopted by an Australian couple, finally won her Swiss citizenship.

She had almost given up. But now, Australian Cate Riley’s long fight now has a happy ending. The Administrative Court of the Canton of Zurich has granted her the right to Swiss citizenship. “I have to pinch myself to believe it,” says Riley on the phone from Australia. But what happened?

Riley’s story began in Sydney in 1970, where she was born to Swiss parents and given the name Margrith. She was conceived during the short-lived relationship between her biological parents, at a time when authorities were urging unmarried women to give up their children for adoption. The practice was booming in Australia at the time – there were 10,000 adoptions in 1970 alone, and societal pressures were denying women the ability to care for their children alone.

Her birth mother, who was a Swiss woman living on her own in Australia, had no choice but to give her daughter away. “At the time, these mothers were expected to forget about their child and carry on living as if nothing had happened,” Riley told SWI swissinfo.ch in 2023.

In winter 2023, Riley travelled to Switzerland with her family to seek out her roots, but it was also the starting point for the fulfilment of a dream come true. Riley wanted to become a Swiss citizen.

>>> Cate Riley was in Switzerland with her family in 2023. We met her:

It was a seemingly impossible endeavour. By this point, Riley had faced multiple rejections from Swiss authorities. In 2017, for example, the Swiss Consulate General in Sydney wrote that, because she had been adopted, she would not be able to obtain Swiss citizenship.

In 1971, when Riley came to live with her adoptive Australian parents, they christened her Catherine Nicole. Although Cate learnt early on that her biological parents were not from Australia, she wasn’t able to see her adoption files until 1991.

At that point, Riley immediately set out to find her biological parents. First, she sent a letter to the Swiss National Tourist Office, requesting information about her heritage with a copy of her birth certificate enclosed. She was 20 years old at the time. It took her five years to find her biological mother. Another year later, she was able to find her biological father.

Denied time and again

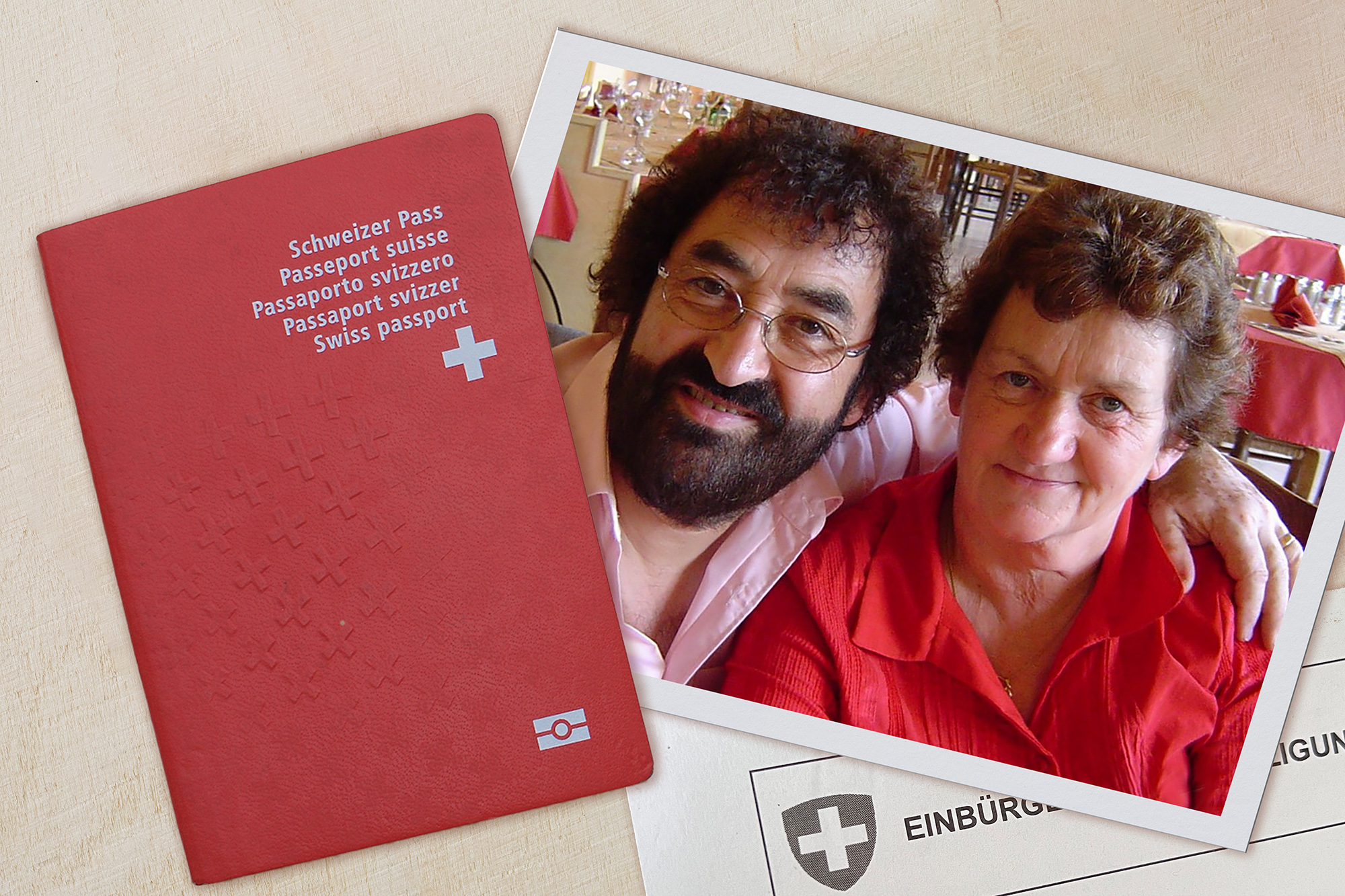

Riley’s biological family welcomed her with open arms. Her biological mother was still living in Australia, while her biological father, who had returned to Switzerland, travelled back down under to meet her.

At a reunion of her Swiss family in Australia, Riley realised that her half-sisters – who are only half Swiss, had Swiss passports, while she did not. This realisation sparked Riley’s determination to become a Swiss citizen so she could fully feel like part of the family.

Her enquiries and efforts just led to rejections. After her experience with the Swiss consulate in 2017, Riley tried the Civil Status and Citizenship Service of Canton Bern in 2022. They forwarded the request to the municipal office of canton Zurich because the birth mother’s hometown was in Zurich. Here, too, the answer was negative, this time with a different reason: “Swiss citizenship was forfeited in autumn 1992”. At the time, Swiss citizens abroad had to register with a Swiss representation or authority by the age of 22 (now 25) in order to retain their nationality. In the fall of 1992, Riley turned 22.

Riley nearly resigned herself to failure but, over the years, her sense of injustice only deepened. “I’m Swiss after all, my blood wasn’t exchanged when I was adopted,” she points out.

Giving up was out of the question.

All the authorities had been mistaken

Swiss lawyer Marad Widmer finally took up her case. The authorities had often rejected his client on the grounds that Riley had been adopted in Australia and had therefore lost her Swiss citizenship. “However, my first realisation was that the adoption in Australia had no legal relevance to this case. All the authorities had been mistaken,” he explained.

This is because, at the time of Riley’s birth in 1970, adoption did not result in the acquisition or loss of Swiss citizenship. Riley therefore remained Swiss despite having been adopted. The reason? According to Swiss citizenship law, the link to the family of origin remained intact in the event of an adoption, the person retained their citizenship, and even remained entitled to an inheritance. This was called a “simple adoption.” Only after 1973 did the law change, when so-called, “full adoption” was created, which made an adopted child’s legal status the same as a biological one.

However, the authorities did not take this legislative development into account. “We had to prove that Riley had never lost her Swiss citizenship,” says Widmer. And although Riley’s application for Swiss citizenship was rejected by the municipal authorities in Zurich, the authorities recognised that Riley was Swiss until her 22nd birthday. “That was a small consolation for my client,” said Widmer.

Successful appeal

Riley, now 54 years old, filed an appeal, but Canton Zurich’s Department of Justice also rejected the request. So, Riley lodged an appeal with the Administrative Court. And this is where a once seemingly negligible document came into play. Riley had held onto the old envelope from the Swiss National Tourist Office, which was part of the Swiss Consulate General in Edgecliff. Inside was a map of Switzerland with her biological mother’s hometown of Zurich clearly marked.

This was the key document proving that Riley had registered with the Swiss authorities in good time. While the lower courts had ruled that this contact did not fulfil the requirements for a notification, the Administrative Court of the Canton of Zurich decided in Riley’s favour in August 2024.

The court ruled that the law at the time didn’t clearly define what qualified as “sufficient notification.” The Administrative Court decided on a more flexible and broad reaching interpretation, stating that, in cases of doubt, citizenship should be presumed to be valid. Consequently, the court ruled that Riley retained her Swiss citizenship, and the ruling is now set into law.

Riley is very happy about it. “But I don’t think it will feel real until I hold the passport in my hand,” she says of this latest step in a long-running search for her roots and her identity. “Now I’m no longer just a tourist when I come to Switzerland, I’m part of it now.”

The crucial piece of evidence?

According to Widmer, the envelope from the tourist office was “a crucial piece of evidence.” Ultimately, the correct legal argument was what clinched her victory.”

“Riley has made consistent efforts over the years to build and maintain connections with both her Swiss family and with Switzerland itself,” says Widmer. “The decision of the Zurich Administrative Court is therefore correct not only in legal terms, but on a human level.”

Edited by Balz Rigendinger/me. Adapted from German by David Kelso Kaufher/ds

More

Going on a quest for a Swiss passport – as a Swiss national

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.