Face time: the terrifying Swiss tradition of Tschäggättä

When night falls, ancient, eerie figures roam the villages of a mountain valley in southwestern Switzerland. They are the Tschäggättä. Two young carvers explain how they keep the tradition of wooden masks alive.

The floor of Elia Imseng’s workshop is covered with wood splinters and shavings; the air smells of stone pine. On the workbench, locked in a vice, is the study of a mask. The eyes, nose and mouth have already taken shape. “I started carving it yesterday,” Imseng says, explaining that it will take him about 20 hours to finish. “I hardly ever follow a precise plan. I let myself be inspired by the piece of wood.”

Imseng, 26, has creativity in his blood. His great-grandfather, then his grandfather and finally his father were mask carvers in Kippel, in the Lötschental valley in Upper Valais. He started carving as a child. With his brother, Andrea, he followed his father’s creative process in the family workshop and made his first sketches of masks on a wooden board, then asked his father to turn them into reality.

Today, Imseng, a forester by profession, and his brother are the guardians of this family tradition. “I’ve made around 20 masks so far, each with unique characteristics,” he says. “Sometimes I draw inspiration from characters in horror or science fiction films, but mostly I make primitive-style masks, faithful to tradition.”

Some of them – the ones dearest to the Imseng family, made by his grandfather – are hanging on the walls. They are the few that remain because, in the 1950s and 1960s, they represented an important source of income – costing CHF50-CHF100 ($55-$110) each – for a family economy based mainly on farming. “Each mask has a special meaning or evokes a special memory, which is why I never sell them,” Imseng says, explaining that when a mask is well made, its facial expression must be able to tell a thousand stories.

The transformation

While the masks take shape in the workshop below the house, about 200 metres away, in a room in the underground car park in Kippel, Elia and Andrea turn into Tschäggättä (pronounced “cheggerter”). More than a hundred masks, made by three generations of Imseng sculptors, line the walls. This room has everything necessary to become the ancestral figure who, roaming the streets of the valley, triggers fear in young and old alike. There are around 15 carvers and 12 so-called Maskenkeller (mask cellars) in the Lötschental.

With his brother’s help, Andrea begins his metamorphosis. He first wears rough jute trousers and an old jacket that has been turned inside out. On his shoulders he places a padding that makes him appear more imposing. Then he slips his head into a poncho of Valais goat fur with a black collar, secured at the waist by a strong belt with a large bell, called “Triichla”. To protect his hands from the cold, he wears the typical “Triämhändsche”, woollen gloves worn inside out. And finally, the main element: the wooden mask, whose size can vary from 30 to 50 centimetres. Elia Imseng chooses one of his creations: a brightly coloured mask with intellectual spectacles and a pronounced chin.

Aura of mystery

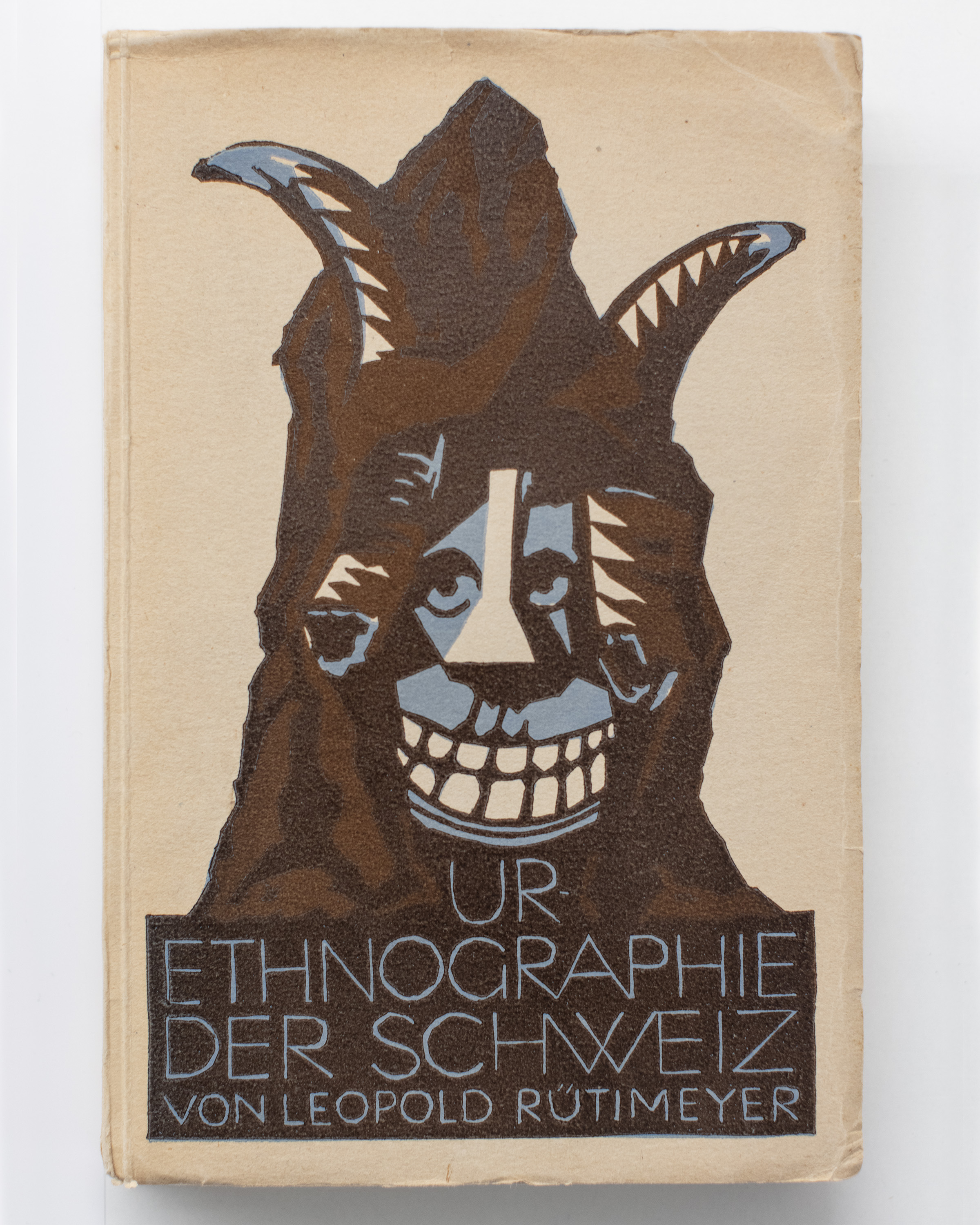

“There are numerous legends and theories circulating about the origin of the wooden masks from the Lötschental, but none of them has a solid scientific basis,” says Rita Kalbermatten, curator of the Lötschental Museum in Kippel.

According to Thomas Antonietti, ethnologist and co-curator of the museum, the fascination of this tradition lies in the aura of mystery that surrounds it. “The first written record dates back to 1860, when prior Johann Baptist Gibsten banned the use of masks during carnival, describing the Tschäggättä as eerie figures with faces covered in wooden masks, adorned with horns and wrapped in animal skins,” he says.

Antonietti then outlines the two most reliable theories. The first suggests that the tradition arose from the thefts committed by the “Schurten-Diebe”, thieves who lived on the shady side of the valley and disguised themselves to plunder farms on the sunny side of the valley. The second theory links the Tschäggättä to the demonic figures that appeared in ecclesiastical Baroque theatre.

Discovery and commercialisation

Friedrich Gottlieb Stebler, professor at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, was among the first to study and document the Lötschental masks. In 1907 he published a monograph on the valley. In 1916 he invited the American film producer Frederick Burlingham to make a documentary entitled La Suisse inconnue: La vallée de Lötschental (Unknown Switzerland: the Lötschental Valley). “In the film, a group of young people wearing wooden masks and furs perform a ritual dance in Blatten, curiously in the middle of summer,” Antonietti says.

The first important appearance of the Tschäggättä outside the valley dates back to 1939, on the occasion of the National Exhibition in Zurich. “In the context of spiritual defence, Alpine traditions, including the Lötschental masks, became symbols of Alpine culture,” Antonietti points out. In just a few decades, what was once a local tradition was thus transformed into an element of cantonal and national identity.

This growing notoriety captured the attention of the urban population. Tourists staying in the Lötschental want to take home a souvenir: a wooden mask. “To satisfy this demand, between the 1950s and 1970s, craftsmen began to make and sell less elaborate masks to hang on walls,” Kalbermatten explains.

Changing to survive

According to tradition, the Tschäggättä were only allowed to make their raids in the village lanes between noon and 7pm, until the Ave Maria bells rang. Their aim was to instil fear and respect, especially in children and young women. “It was a custom reserved for unmarried men,” Antonietti says. “It was almost their only opportunity to meet unmarried women without the supervision of parents or the parish priest.”

With the economic and social development of the valley, since the 1970s the tradition has undergone major changes: the Tschäggättä also appear at night and the masks are also donned by married men, women and children. Events such as the Tschäggättu-LoifExternal link on “Fat Thursday” and the parade in Wiler on Carnival Saturday are also organised.

For Elia and Andrea Imseng, the tradition is also perpetuated in a more spontaneous way. “With friends we go around Kippel and its restaurants. We then finish the evening in the Maskenkeller, where we remember the funniest moments of the evening.”

We leave the brothers in their room packed with family heirlooms, as they look at the masks made by their father and grandfather, imagining the stories they could tell.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Adapted from Italian by Thomas Stephens

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.