‘That mummy is my great-grandfather’

Every family has mysteries, but few involve an ancestor who was mummified. The anecdote of Claudio Mazzucchelli’s “Pasha great-grandfather” circulated for decades among the former diplomat’s family. But while Mazzucchelli was in Egypt on behalf of the Swiss foreign ministry, the unlikely-sounding story was confirmed.

Cairo, 1992. Claudio Mazzucchelli had been Swiss consul to Egypt, a country to which he is particularly attached, for two years. Mazzucchelli, whose mother was born in Egypt, tells SWI swissinfo.ch that his duties included travelling to Alexandria once a month to bring pensions, in cash, to a handful of elderly Swiss living in the city. His contact in Alexandria was a lady who knew his family well.

One day the phone rings. The lady in Alexandria has disturbing news: “The body of a Swiss man is in the morgue.”

Maybe a tourist has had an accident, Mazzucchelli thinks. Maybe he’ll have to take one fewer pension to Alexandria. His doubts turn to disbelief when the lady tells him: “It’s the mummy of your great-grandfather.”

The Appenzell Pasha

Herisau, Appenzell Outer Rhodes, 1837. A baby boy, Johannes, was born in the home of the Schiess family. No one in the small village in northeastern Switzerland could have imagined the child’s peculiar fate.

A medical student in Basel and later in Bern, Johannes Schiess practised his profession in Paris and Berlin and then travelled to Crete with an “Italian-Swiss committee that lavished care on the insurgents” of the Cretan uprising of 1867-1869, reads a document on the back of a photograph of Schiess, dated 1907. It is a brief biography of the doctor, “a man for whom the city of Alexandria has just celebrated a solemn funeral”.

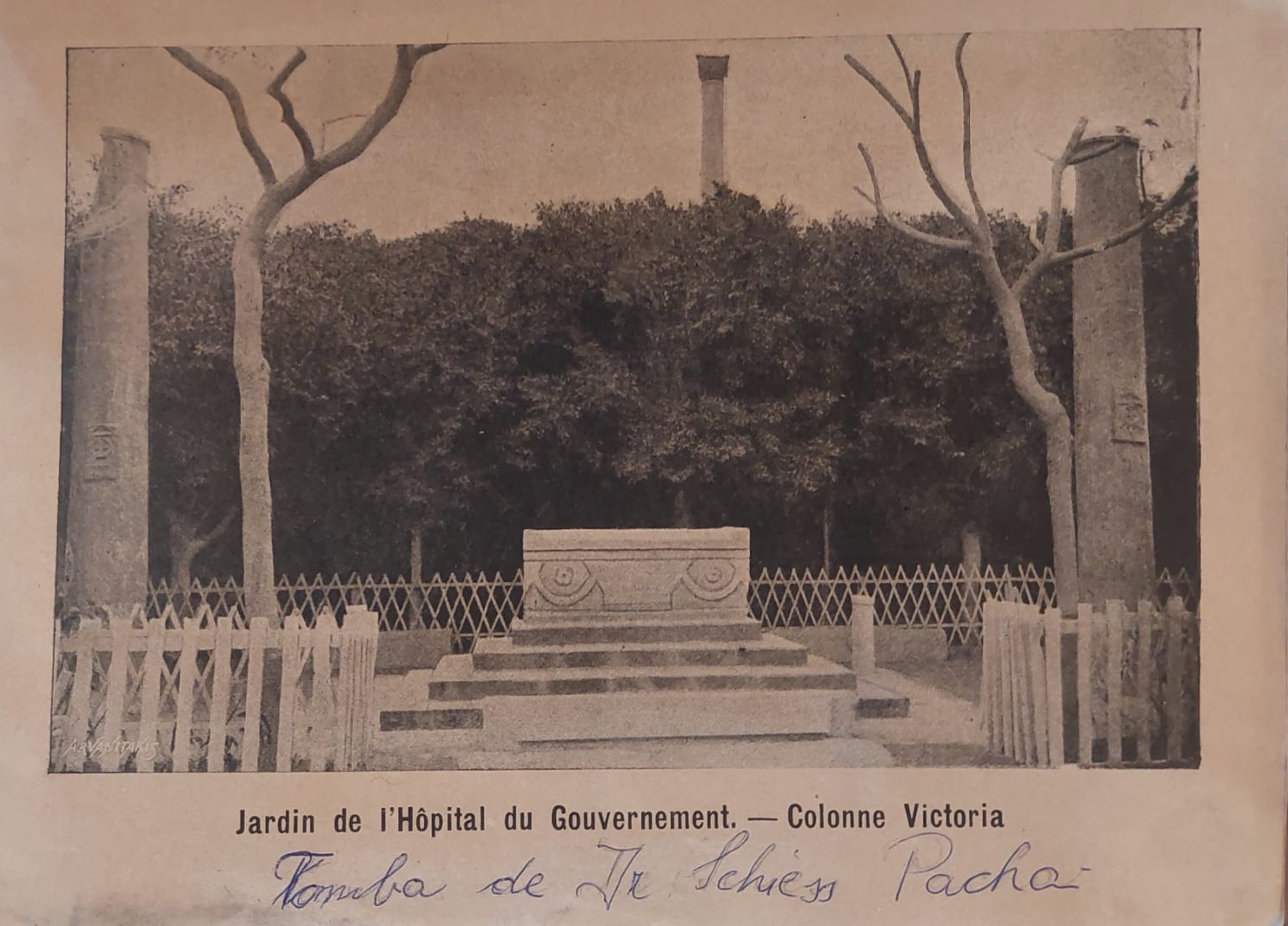

It is not known how, but in Crete Schiess came into contact with members of Egyptian high society. In 1869 he was invited by Isma’il Pasha, the Khedive of Egypt and ruler of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, to the inauguration of the Suez Canal. For Schiess this was a turning point, a thunderbolt. He liked the region so much that he decided to move to Alexandria. He made a career at the State Hospital, of which he became director, expanding it and creating a laboratory where illustrious names came to study.

He collaborated intensively with, among others, the German doctor Robert Koch, considered, with Louis Pasteur, to be the father of modern bacteriology. Claudio’s niece Martina Mazzucchelli points out that the website of the Robert Koch Institute has, among other things, several letters that Schiess sent to Koch. In recent years Martina has collected an enormous amount of documents – newspaper articles, postcards, photographs – concerning her ancestor.

Schiess also became a prominent figure in city politics. The caption of a photo held by Claudio Mazzucchelli reads: “His Excellency Dr. Med. Johannes Schiess Pasha, Mayor of Alexandria”.

It is not clear whether he actually held the office of mayor, but the back of the photograph specifies that he was vice-president of the city council.

Schiess’s great passion, however, was archaeology. The document says that the State Hospital stands on the site of the Ptolemaic dynasty palace, and Schiess organised fruitful excavations there. Later, thanks to his support, numerous other expeditions were carried out throughout Egypt.

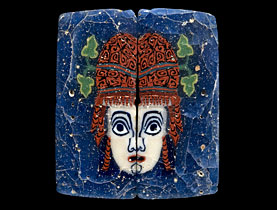

“He was one of the founding members of the Archaeological Museum of Alexandria,” Mazzucchelli says, referring to the Greco-Roman museum, which still exists today. Johannes Schiess specified in his will that he wanted to be embalmed “like a mummy”. “He must have been a bit of a peculiar chap,” his great-grandson adds.

The mystery of the sarcophagus

Schiess’s granddaughter, Claudio Mazzucchelli’s mother, left Egypt with her parents in the 1950s, after the coup d’état led by Gamal Abdel Nasser – as did many other foreigners. The destination is Ticino, home of her father.

“When I was a child, I often heard the story of my great-grandfather, the Pasha,” Claudio Mazzucchelli says. Pasha is a high-ranking title in the Ottoman Empire. It was known that Schiess had himself mummified and placed in a large granite sarcophagus in the gardens of the State Hospital in Alexandria. In the 1960s, however, the sarcophagus vanished, possibly stolen. Traces of its tenant were also lost – until a phone call in 1992.

The mummy re-emerged while the University of Alexandria was re-organising its huge cellar. Johannes Schiess was in a wooden crate with an identifying plaque. The university delivered the body to the morgue, where it remained for a few months. “At some point they had to make room for fresher corpses,” Mazzucchelli says. The authorities contacted the lady in charge of Swiss interests to find out what to do with the mummy.

Schiess is now buried in the Anglican cemetery in Alexandria. His second funeral was attended by Mazzucchelli, his wife, the director of the archaeological museum, a priest and a few other people. Not exactly the solemn ceremony of the first. Would the Pasha have had something to say about it?

“Had I not been consul in Egypt at the time, we would probably never have known what happened to him,” Mazzucchelli says. “My wife always says that it was written in the stars and that it was he, my great-grandfather the Pasha, who wanted it.”

Translated from Italian by DeepL/ts

More

More

From cakes to mosaics

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.