Spell check: the Swiss origins of the European witch craze

Six hundred years ago a grisly witch hunt in the Simmental, a valley in canton Bern, was described in a book. This went on to become the blueprint for witch hunts throughout Europe.

Around 1400, several people were accused of witchcraft in the Simmental in the Bernese Oberland. The centre of attention was a man from the village of Boltigen who had allegedly used magic to cause miscarriages, damage livestock and destroy crops. Under torture, he confessed to having made a pact with the devil.

Stories also exist of sorcerers who belonged to a sect and who worshipped the devil, murdered children and practised cannibalism. They were all sentenced to death.

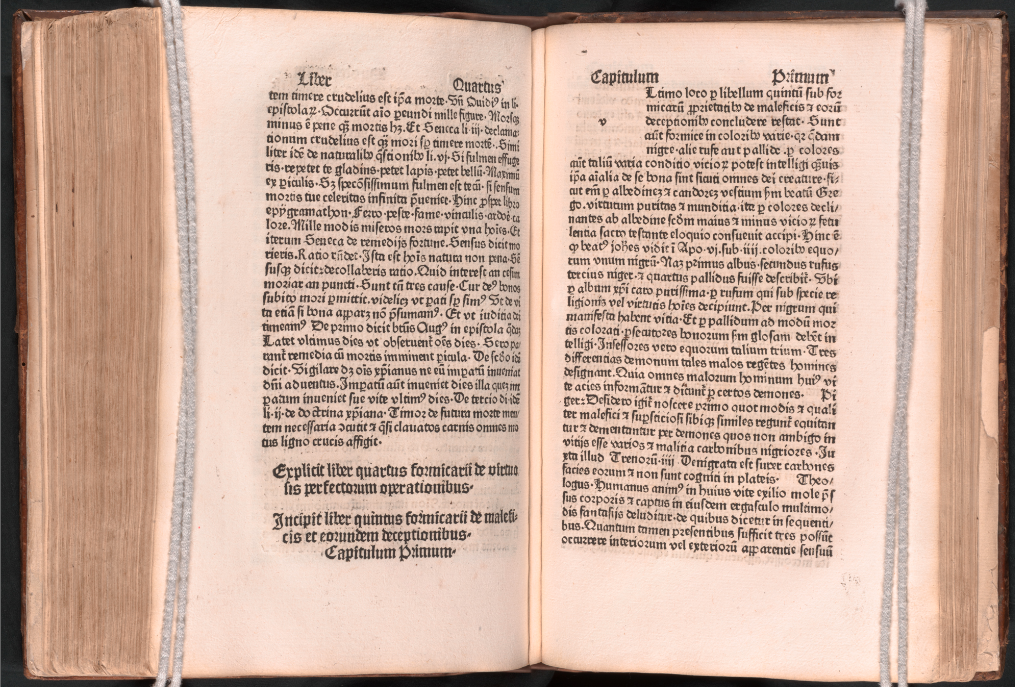

All this can be found in the book Formicarius by the German Dominican theologian Johannes Nider. Written in 1430, the book, a moral treatise to instruct young Dominicans, became a central source for the infamous Hexenhammer (Malleus Maleficarum), a textbook for the witch hunts that claimed thousands of lives across Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

“The testimonies collected by Nider contributed significantly to the spread of the belief in witches and in particular the idea of the witches’ Sabbath in Europe,” says Catherine Chêne, a historian at the University of Lausanne who specialises in early witch hunts in Switzerland.

But did the witch hunt in the Simmental described by Johannes Nider really take place? Historians are not sure.

One problem is that there is only one source: the Formicarius. Experts see a second challenge in the fact that the reports from the Bernese Oberland were a major novelty, as they contained elements of the witchcraft legend that didn’t appear elsewhere until later.

From Jews to witches

At the time of the Simmental witch hunts, persecution by the Church of people of other faiths, so-called heretics, had been going on for a long time, dating back to the 12th century. The persecution of the Waldensians, a forerunner movement of Protestantism, in the 14th century was a precursor to the witch trials, at least in Switzerland.

Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg argues in his book Witches’ Sabbath – Deciphering a Nocturnal History that in the 14th century the church-led pogroms against Jews, the persecution of lepers and finally the great plague that struck Europe from 1347 onwards prepared the ground for the first witch hunts in Central Europe.

Gradually, the enemy images expanded, from the small circle of lepers to witches and sorcerers, who could basically be anyone. However, the great wave of persecution did not begin until the 15th century, which would make the events in the Simmental a very early – possibly even the first – case.

More

How Christian Europe created anti-Semitism in the Middle Ages

Central elements of later witchcraft accusations were recorded there for the first time, such as the pact with the devil, the Sabbath and the idea that the witches and sorcerers could use the devil to cast damaging spells (maleficium).

Catherine Chêne’s historical research in Bernese archives shows that there were trials against sorcerers in the Bernese regions from the early 15th century. “However, belief in the witches’ Sabbath did not yet play a role, unlike in the French-speaking part of the diocese of Lausanne.”

First witch hunts

The fact that the first witch hunts mainly occurred in western Switzerland can be explained, among other things, by the fact that a functioning Inquisition existed there after the Waldensian trials. In addition, the entire region and western France in particular had become the focus of the Church after Pope Alexander V, elected in 1409, ordered the Grand Inquisitor in charge to take action against emerging sects with “forbidden rites”.

More

Uncovering myths and truths behind Swiss witchcraft trials

“The nature of the accusations in the Simmental reports was a novelty and could have been compiled by Johannes Nider from other sources and attributed to his main informant, a judge named Peter, in order to lend them more legitimacy,” Chêne says.

The identity of this Bernese judge is still unclear, which makes the search for facts more difficult. Most historians working on the subject assume that it was Peter von Greyerz, who was Bernese bailiff in the Upper Simmental between 1392 and 1406.

“However, my archive research shows that other bailiffs with the name Peter are also possible,” Chêne says. “For example Peter Wendschatz (1407-1410) or Peter von Ey (1417). There are no records of the identity of the bailiffs between 1418 and 1432.”

Political tensions

But if the reports from the Simmental are fiction, why would people make them up?

As with most witch hunts, social tensions provided the breeding ground. This was also the case in the remote Bernese Simmental at the time.

The political changes in the Upper Simmental from 1389, following its incorporation into Bernese territory, could have led to conflicts between Bern and its new subjects.

The pattern for this is well known. “Studies on a witch hunt in Valais in 1428 have shown that the persecutions there were based on a conflict between Baron Guichard of Raron and his Valais citizens,” Chêne says.

A brief echo of possible tensions in the Upper Valais can also be found in the Formicarius: in one passage it describes how Judge Peter fell victim to a “vicious” attack: four men and an old woman had attacked him in response to one of his judgements.

The witchcraft accusations could therefore have served as an effective tool for the judge to persecute his opponents. And his reports in turn provided Nider and later the authors of the Hexenhammer with good material to propagate the idea of a widespread witchcraft conspiracy.

More

‘Anna Göldi was like a wild horse, impossible to catch’

Personal paranoia

In addition to political tensions, the judge’s personal circumstances may also have played a decisive role. Peter von Greyerz suffered from paranoid delusions, historian Kathrin Utz-Tremp wrote in her paper Ist Glaubenssache Frauensache: Zu den Anfängen der Hexenverfolgungen in Freiburg (Is faith a woman’s matter: on the beginnings of the witch persecutions in Fribourg).

At the end of his term of office, von Greyerz left Simmental completely exasperated and hysterical and then “lamented his suffering to Johannes Nider, who reinterpreted the story in terms of witchcraft”, she wrote.

It’s possible that Greyerz had trouble with the unruly mountain population in the Upper Simmental, who perhaps also clung more strongly to superstition. This attitude towards the highlanders can also be found in Johannes Nider.

Nider reckoned that the shortage of preachers had resulted in a great deal of ignorance, which made the population susceptible to illegal practices. “In one of his anecdotes, he denounces believers who used unauthorised remedies for a curse instead of relying on prayer alone,” Chêne says.

Whether cultural or political tensions, personal hysteria or actual witches and sorcerers, it’s clear that around 1400 there were political and social tensions in the Upper Simmental, which found expression in witchcraft legends. Through their reproduction in the Formicarius and later in the Hexenhammer, they laid a central ideological foundation for the devastating waves of persecution that plagued the whole of Europe in the following centuries.

More

No one tortured witches like the Swiss

Edited by Balz Rigendinger. Adapted from German by Thomas Stephens

More

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.