Swiss start-up plans promising alternatives to plastic

Bloom Biorenewables uses wood, straw, cherry stones or walnut shells to make bioplastics, textiles, cosmetics and perfumes. The Swiss start-up has developed a technology for producing materials from biomass instead of oil.

“When I started studying chemistry, the focus was overwhelmingly on petrochemicals, that is, the transformation of petroleum. Whereas now, green chemistry is increasingly being taught,” says co-founder and chief operating officer Florent Héroguel. “We hope that the chemists of the future will no longer use oil, because we can do without it.”

The fledgling company, which began as a spin-off from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), wants not just to dispense with oil in chemical research, but also to replace it in everyday life. The polluting material accompanies us everywhere: it is in our clothes, shoes, smartphones, computers, furniture, packaging and bottles. Petroleum derivatives also turn up on our plates in the form of flavours, such as vanillin, in perfumes, cosmetics and detergents, and even in medicines.

“Great progress has been made in the energy field in developing alternative sources to oil,” Héroguel says. “But when it comes to materials, we’re still in the early days, and it’s probably even more difficult. A different source of carbon is needed. It’s found in atmospheric CO2 but is difficult to recover, and in biomass. What we are doing is retrieving the carbon from biomass, as we can use it to make sustainable and circular products.”

Not just bioethanol and paper

The biomass used in EPFL’s Laboratory of Sustainable and Catalytic Processing, with which the start-up is collaborating, is made up of wood, tree bark, leaves, cherry and peach stones, walnut shells and other lignocellulosic material from different countries, including Switzerland. Lignocellulose is the most common raw material on our planet and contains three main elements: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin.

Biomass is increasingly being used to produce bioethanol, but it has properties that mean it could replace petroleum in many other ways. “Up to now, its main industrial use was in papermaking. But for that, only 40% of the wood is extracted; the rest is burned or thrown away. We want to recover at least 75% of the lignocellulosic biomass to provide an alternative to oil,” Héroguel explains.

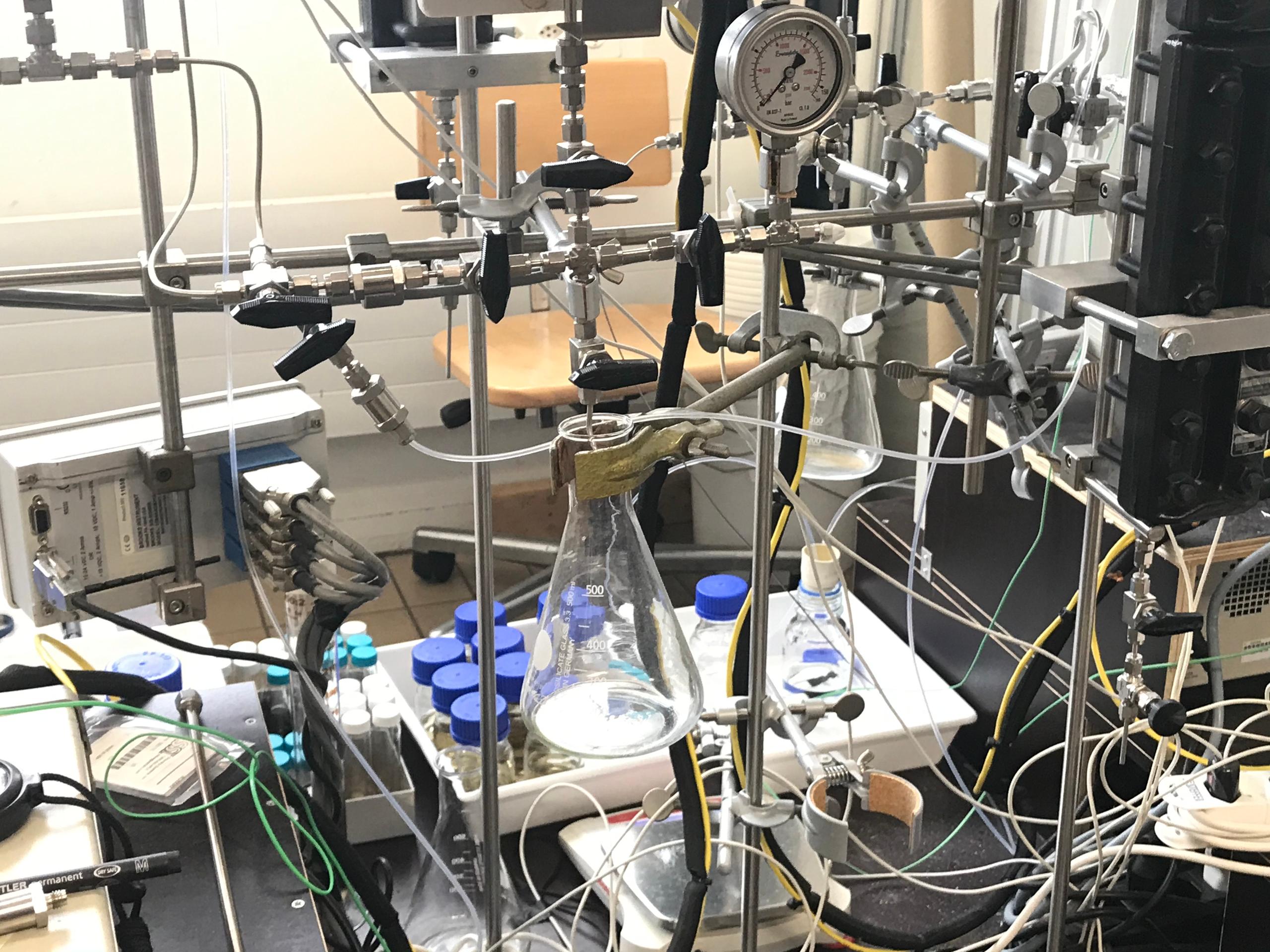

For their tests at EPFL, researchers from Bloom Biorenewables use a ten-litre reactor in which biomass is heated and treated with solvents to produce several different elements. The first fraction, cellulose, is recovered using a filter. A liquid containing lignin and another containing hemicellulose are then separated out. After that, these elements are isolated, purified and tested using a range of equipment available in EPFL laboratories, such as incubators, centrifuges and chromatographs.

Textiles and bioplastics

“The cellulose could be used to produce paper, but our goal is to extract as much as we can from it, for instance to make textiles. Today, there is not enough cotton to keep up with demand, so most textiles are made from petroleum, such as polyester or acrylic. However, the textile industry is increasingly looking for ways to manufacture more environmentally friendly products, as polyesters are harmful to the environment,” Héroguel says.

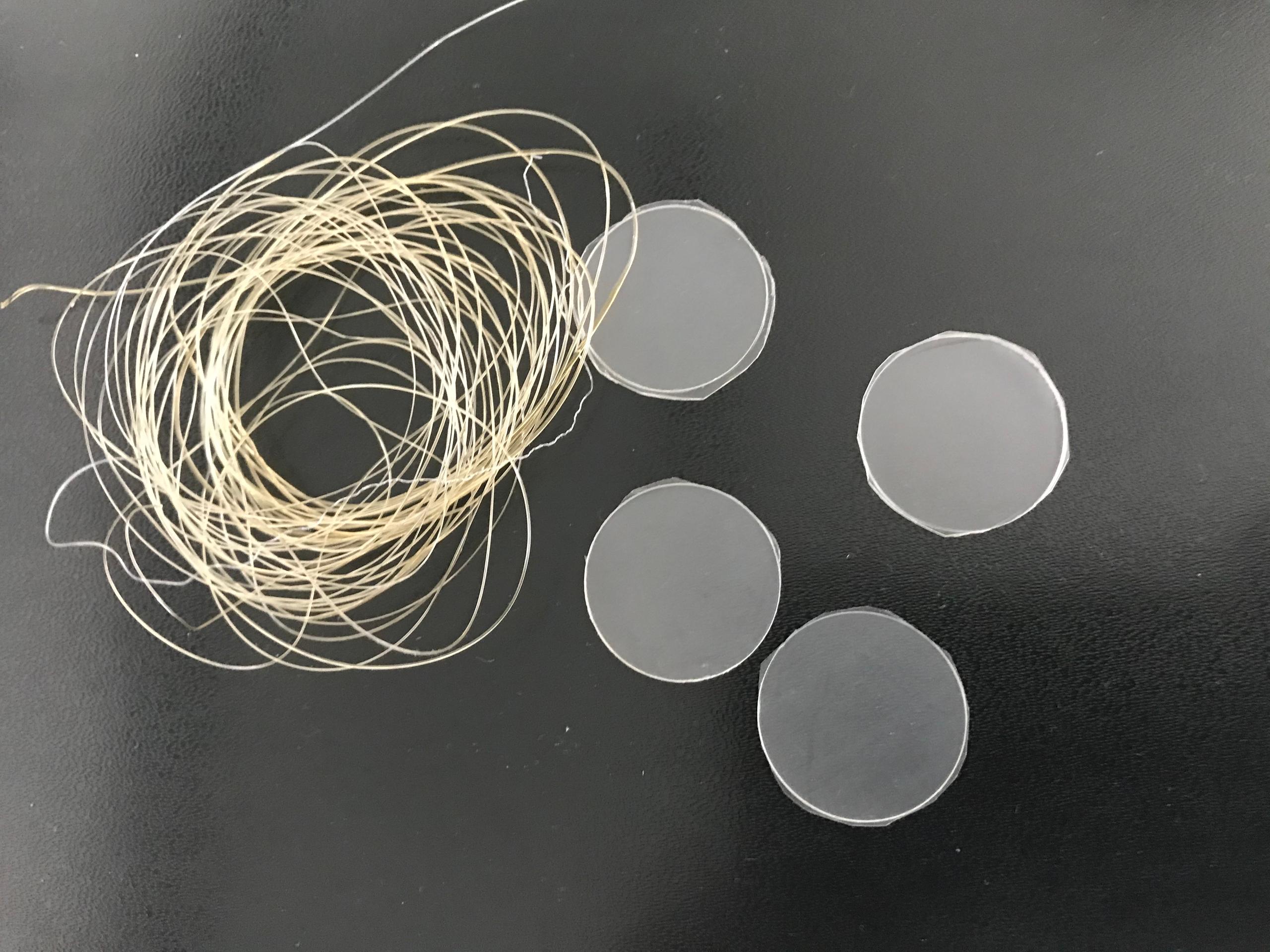

Some textiles are already being produced from biomass today. The leader in the sector is an Austrian company. In Switzerland, new projects are cropping up. “But there are still a number of open questions as to the feasibility and potential of the processes currently in use. We’re therefore working with different partners to develop alternative, less polluting and more efficient methods, using vegetal waste that doesn’t just come from forests,” he says, holding up some transparent bioplastic yarn made from cellulose extracted in the laboratory.

The start-up has also begun working with partners to exploit the properties of hemicellulose, which is particularly suitable for producing bioplastics. These are slated to replace polypropylene packaging.

The issue is highly topical, as the EU is seeking, through its new Circular Economy Action Plan, to cut waste, enforce the use of sustainable plastic in packaging and other products and increase producer responsibility. Food giants like Nestlé and Danone have announced their intention to achieve a carbon-neutral footprint within a few years by replacing the packaging used today with plant-based products.

Flavours and fragrances

But the element on which the start-up is pinning its greatest hopes is lignin. “The lignin found on the market today condenses during extraction, so it degrades and becomes very dark. Our process stabilises it, preventing it from condensing and degrading. As a result, we can extract a very pure and light-coloured lignin that can be used to make cosmetics, for example. Or it is depolymerised under relatively mild conditions in order to extract aromatic molecules for the food and perfume industries,” Héroguel says.

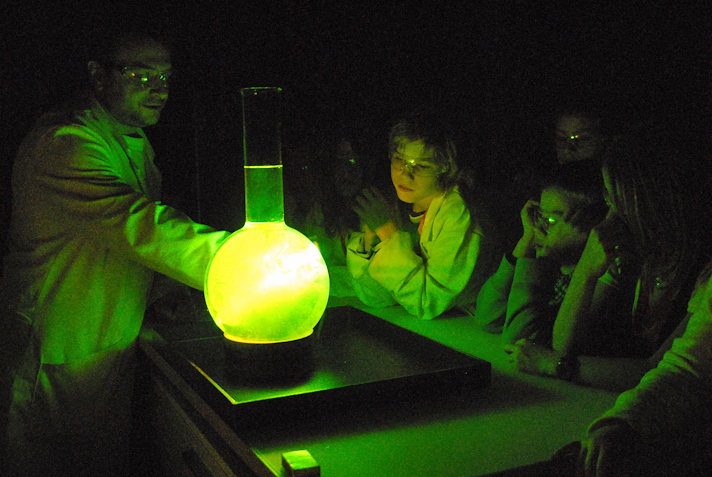

The food and perfume industries are also looking for new plant-based materials to replace petroleum. For several years, researchers from Bloom Biorenewables have been testing different possible applications with companies active in these sectors which have built up solid experience in producing molecules for vanillin, eugenol and smoky flavours.

“We began our research at EPFL, in the laboratory of Professor Jeremy Luterbacher, in 2015, with the goal of finding better ways to exploit biomass. We soon realised that lignin had the greatest potential and the largest market. Today, no one is able to produce lignin of this quality, which can be used for products with a high added value such as perfumes.”

From the lab to the market

In 2017, the young EPFL researchers filed a first patent application for the production of lignin. In light of the positive reactions of the scientific community, Bloom Biorenewables was founded two years later by Héroguel, Luterbacher and Remy Buser, in order to industrialise this laboratory technology.

The start-up – which has already won several awards, for instance from the W.A. de Vigier Foundation – soon won over investors. Last August it secured funding worth over CHF3 million ($3.3 million), invested in part by Japanese company Yokogawa, which operates mainly in chemicals and energy.

These funds will, in particular, help pay for the company’s new head office in Marly, near Fribourg. Thanks to cooperation with the School of Engineering and Architecture of Fribourg (HEIA-FR), the researchers will now be able to use much larger reactors (600 litres) to produce lignin and other substances extracted from biomass. Access to this laboratory will enable them to continue their experiments with different partners, with a view to filing new patent applications and starting the commercialisation phase. In 2022, the company plans to build a factory, at an estimated cost of CHF30-50 million in order to launch industrial production.

“From one tonne of biomass, we hope to be able to extract 750 to 900 kilos of matter for the production of textiles, bioplastics and lignin, which is a very high ratio,” Héroguel says.

He is convinced that this new technology will help not only protect the environment, but also give chemistry a new image.

“Even today, when we say we are chemists, many people look at us askance and think that what we do is not clean. Whereas, in reality, with chemistry we can make a great contribution to protecting our planet.”

More

Why don’t the Swiss recycle more plastic?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!