Swiss hydropower prepares for future energy shortage

The severe drought in Europe has hampered hydroelectric output across the continent. As glaciers rapidly melt, Switzerland’s hydropower reserves are currently below-average but stable. Will they be enough to help prevent an electricity shortage this winter?

At the Salanfe dam at the foot of the snowless Dents du Midi peaks in southern Switzerland, thirsty cows gulp down water from the slowly shrinking reservoir. This summer the mountain lake is about 15 metres lower than normal after losing 8 million cubic metres of water.

“It’s an exceptional year,” says the waitress at the Auberge de Salanfe hostel overlooking the reservoir. “There is no more glacier, so the lake only gets melted snow.”

While the levels of some Alpine dam reservoirs are much reduced this summer, others are surprisingly full – even overflowing – especially those below melting glaciers (click on video below). Surrounded by thick pine trees, the 122-metre Gebidem dam in canton Valais holds over 9.2 million cubic metres, or almost 4,000 Olympic swimming pools-worth, of icy-blue meltwater from Europe’s biggest glacier, the Aletsch.

The summer heatwaves have caused the Aletsch to melt at a record rate. As a result, the Gebidem dam received so much meltwater that for several weeks in July and August the precious liquid went to waste. Every second 75,000 litres flowed over the dam into the void before it could pass through the turbines.

Hydropower is a cornerstone of Switzerland’s energy policy. In 2021, the country generated 61.5% of its electricity from hydropower, 28.9% from nuclear energy, 1.9% from fossil fuels and 7.7% from other renewable sources. It typically produces more than enough power in the summer months. But it is forced to turn to imports from Europe to meet the gap when the cold sets in.

That is not usually a problem, but this year power shortages are looming. The war in Ukraine, Russia’s cut-off of gas delivery to much of Europe and the shutdown of half of France’s nuclear power plants for maintenance and repairs are all contributing factors.

Europe’s hot, dry weather has also aggravated the energy crisis. Almost half of Europe is currently affected by extreme drought. Following a dry winter, Switzerland has recorded its second-hottest summer since measurements began in 1864 with three heatwaves. Lakes and rivers, especially in eastern, central and southern parts of the country, have dropped to record lows.

‘On track’

But whereas hydropower generation across Europe was reportedly down 20%External link for the first half of 2022 – Italy, Portugal and Spain were among the worst affected – Switzerland seems to be bucking the trend thanks to glacier meltwater.

Swiss hydropower firms experienced a smaller 12% drop in production for the first five months of this year compared with 2021, according to Jürg Rauchenstein, a member of the Federal Electricity Commission (ElCom).

Yet the severe lack of rain has raised fears about whether sufficient reservoir reserves can be built up to help secure the country’s electricity needs through the coming winter.

The overall fill rate of Switzerland’s 200 biggest dams currently stands at 79% (as of August 29).

Some observers, like Bettina Schaefli, a hydrology professor at the University of Bern, are optimistic about the situation. The fill-rate is below average, but reservoir-filling looks to be “on track”, she says.

“Last winter we had very little snow so there was a lack of water from snowmelt. But the glaciers in dam catchment areas have provided a lot of water this summer,” says Schaefli, who is also president of the Swiss Hydrological Commission. “The dam reservoirs are actually too small to take all the water. At the moment there’s more water coming than what we can actually store for the winter.”

Half of Switzerland’s hydropower comes from dams, the other half is generated by smaller structures along rivers, so-called run-of-river power plants, such as those on the Rhine. These had clearly been hit by the drought, said Schaefli, but she believes losses are being compensated by the large Alpine plants that are operating normally.

Some Swiss hydropower operators and electricity companies even appear to be benefiting from current electricity shortages and high prices.

“It’s a very good situation,” Daniel Fischlin, chief executive officer of the Oberhasli power plant in canton Bern, told Swiss public television, SRF. His firm’s turbines have been running at full speed in recent weeks. “Demand for electricity is great… a certain reserve has already been created.”

More

Switzerland braces for winter energy crunch

Nervous

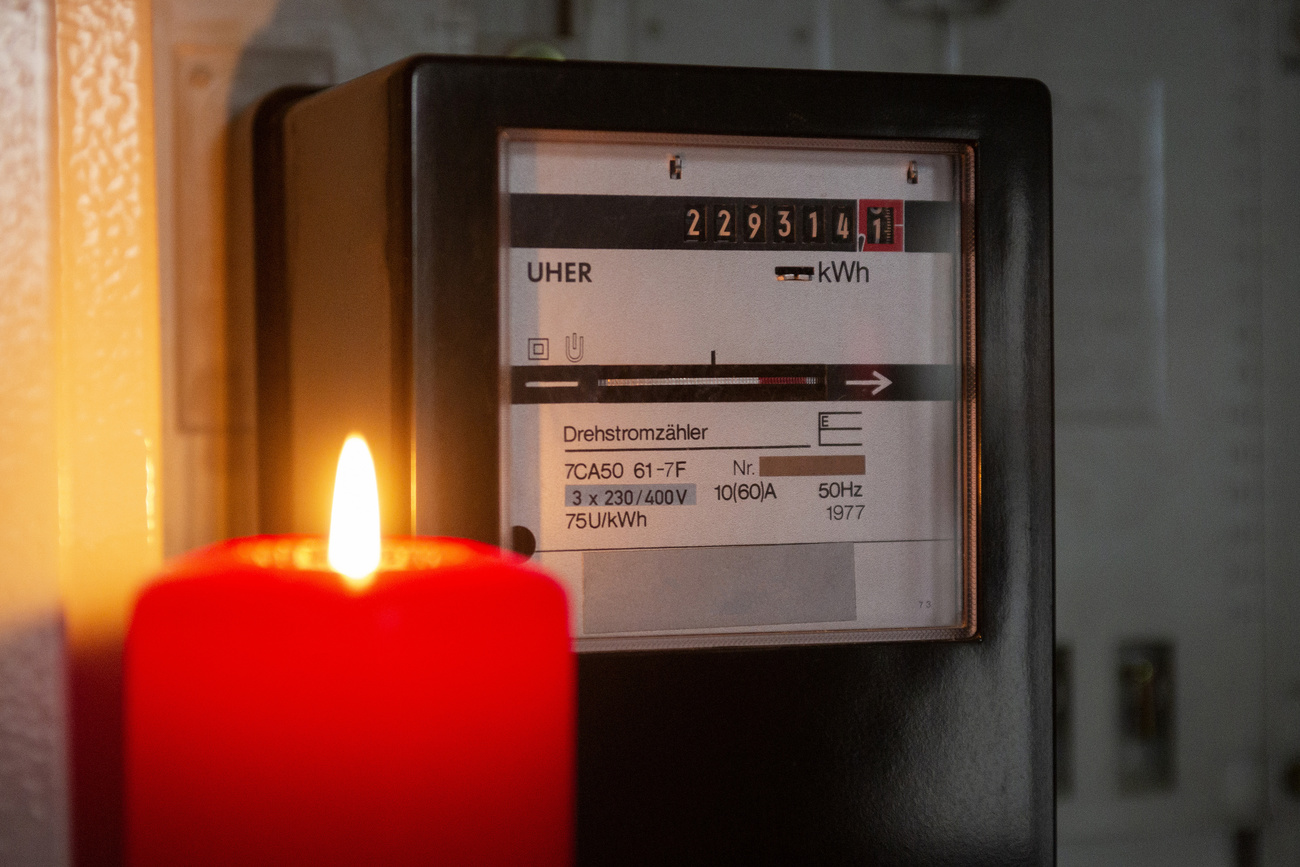

The mounting energy crisis is nonetheless making the Swiss authorities extremely nervous about possible shortages ahead. Power cuts lasting several hours are to be expected, warned the president of ElCom, Werner Luginbühl, in August. His colleague, ElCom Vice-president Laurianne Altwegg, is more circumspect: she says power cuts are not certain.

Switzerland consumed 58.1 terrawatts (TWh) of electricity last year. Around 80% originated from renewable energy sources (68% hydropower and 11% photovoltaics, wind and biomass). Three-quarters were generated in Switzerland by its 682 hydropower plants, the rest was mainly hydropower imported from Norway, Iceland and France, or wind/solar power from Spain. Some 18.5% of the electricity was also nuclear (mostly Swiss).

“The risks of shortages have increased sharply. Power cuts won’t necessarily happen, but they are to be feared,” she told Swiss public television, RTS.

Between May to October, Switzerland typically produces enough electricity via nuclear and hydroelectric power stations to cover national demand and the country exports nearly 30 billion kWh. But in winter, it has to import 5 TWh of additional electricity. For this coming season ElCom estimates that it will need 3 TWh (9% of annual consumption) from abroad, RTS reported.

The map below shows Switzerland’s biggest hydroelectric plants

“This figure corresponds to the lack of hydraulic production due to the absence of snow and the drought,” Altwegg told RTS. “Switzerland is lacking power. De facto, if it is lacking in winter, we will have to import more from abroad.”

As well as electricity imports from Europe, she believes the current crisis can also be mitigated thanks to Switzerland’s four nuclear power plants and if rain fills the Alpine dams this autumn.

Energy savings

Meanwhile, the government has launched an energy savings programme to help avert an energy shortage. It also plans to build up a hydropower reserve to help bridge any electricity supply shortages that could arise during the acute period at the end of winter. Normally at the start of the cold season reservoirs are full and are gradually emptied during winter. Now, in return for a fee, ElCom wants hydropower firms to hold back some water – up to 666 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity, or enough to power 150,000 households for a year – that would normally be sold on the open market.

More

Switzerland banks on hydropower reserve to combat energy crunch

“The government wants to make sure that there is a minimum amount there, because since energy prices are going to explode, the owners may be very tempted to sell the electricity when the price is high and not keep it for Switzerland,” says Schaefli.

Will this new emergency reserve, seen as an insurance policy, be enough to help prevent shortages, and worth the expected high costs for Swiss taxpayers? Luginbühl cautions that it will only be able to help the worst supply bottlenecks for two to six weeks during late winter and won’t be much use for a prolonged power shortage in Europe.

Hydropower and climate change: a complex relationship

The climate crisis is leading to more extreme weather events, changes in the water cycle and the rapid retreat of glaciers. Daniel Farinotti, professor of glaciology at the Federal Technology Institute ETH Zurich, believes 2022 could go down in the history books. He recently told the Luzerner Zeitung newspaper that this year Swiss glaciers could shrink by 4% or more, greater than during the previous record year of 2003 (3.8%).

Schaefli at the University of Bern sees hydropower production remaining stable for the foreseeable future, despite the glaciers’ retreat. She led a 2018 studyExternal link that pointed to little fluctuation in power output despite predictions about the disappearance of glaciers for the end of the century.

“Looking ahead, I expect the average total amount of water that we will have each year will remain stable and we will remain the water tower of Europe simply because the mountains will trigger more rainfall,” says Schaefli.

Official climate scenarios predict that by the end of this century precipitation in Switzerland will increase by about 20% in winter and decrease by the same amount in summer.

By 2050, annual hydropower production is not expected to change significantly, according to the Federal Office for the Environment. It estimates a rise from 37 to 45 TWh – up 10% in winter and 4-6% lower in summer due to the expected changes in precipitation.

“There will be a natural shift from summer production to winter production. From an electricity perspective this is good news – nature is going to help us have more electricity in winter,” says Schaefli.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss

More

Switzerland outlines 15 Alpine hydro projects for the future

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.