The pharma holy grail: drugs for you, designed by you

In the age of sensors, wearables, and artificial intelligence (AI), almost everything can be customised to a person’s unique preferences and behaviours. The next frontier is healthcare, according to discussions at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos.

Digitisation presents pharma companies with what Genya Dana, who heads precision medicine for WEF’s Centre for the Fourth Industrial RevolutionExternal link, calls the “holy grail” in medicine: the right drug for the right patient at the right moment.

Imagine that the wearable step tracker on your wrist isn’t just keeping you fit but also sending countless amounts of data to pharmaceutical companies to develop potentially life-saving treatments.

This is at the heart of one of the most exciting, albeit thorniest, developments in healthcare. Big pharma companies like RocheExternal link and NovartisExternal link are combining advances in technology with access to real world data and genetic sequencing to develop drugs tailored to an individual’s unique biomarkers.

Roche Chairman Christoph Franz says that we have only scratched the surface of digitisation’s potential to transform healthcare. In an interview on the sidelines of WEF, he told swissinfo.ch: “We are only at the beginning of a discovery process where the tools of the digital world can help in healthcare.”

More

Roche Chairman on the opportunity of digital in clinical development

The healthcare sector has lagged behind other sectors when it comes to digitisation, according to experts. Gisbert Schneider, who chairs the Computer-Assisted Drug Design departmentExternal link at Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology (ETHZ) and who worked in the pharma industry for many years, recalls the negative images of some AI-type tools from the 1990s. He told swissinfo.ch: “These technologies were associated with films like the Terminator. Acceptance by scientists was one big issue. The availability of data tools was the other problem.”

Fast forward twenty or so years and the industry is making up for lost time. Last year, Roche acquired genetic profiling company Foundation Medicine, Inc (FMI) for more than $3 billion (CHF2.9 billion) and oncology-focused health records company Flatiron Health, Inc to scale up its capabilities for digitisation in healthcare. This builds on its 2008 purchase of Genentech for more than $47 billion.

Last year, Novartis hired Bertrand Bodson to fill a newly created chief digital officer position after senior roles in Amazon and other tech companies. It also launched Novartis BiomeExternal link, a digital innovation lab and a series of open innovation initiatives.

Mark Lee, who is the development lead of personalised medicine at Roche Pharmaceutical, explained in an interview leading up to WEF: “We are able to capture more data than ever before to build a high-resolution portrait of people and how a disease takes its course.”

More

Dr. Genya Dana on precision medicine

The quest for answers

Gisbert Schneider believes the “key question is to what extent AI will be able to predict clinical outcomes and address idiosyncrasies of the patient.”

Franz says the company is on its way, having already gleaned data from medical records, often hand-written by physicians, with the help of its recent acquisition of Flatiron, in a couple of clinical trials. He explained at a media briefing in Davos, that the company was able “to simulate the control arm so we weren’t obliged to look for patients and give them placebos. For us, it is important because it speeds up clinical trials.”

The results helped Roche secure reimbursement approval by the UK National Health Service for one of its cancer drugs. Lee says that this is particularly powerful in cases of rare cancers where there aren’t enough people for a trial. In lieu, they can rely on data compiled from medical records.

Beyond medical records, pharma is also starting to gather data directly from patients through apps, sensors, and wearables. Roche developed Flood LightExternal link, an app that gathers information about the daily lives of multiple sclerosis patients.

“It is similar to assessments by a doctor in a clinic, but these are only done a couple of times a year. On a smartphone, a patient can do this every day,” Lee explains. It also passively measures behaviours to give indications about how someone is managing the disease. The information is provided to the patient and then to healthcare providers and pharmaceutical companies to help tailor therapies.

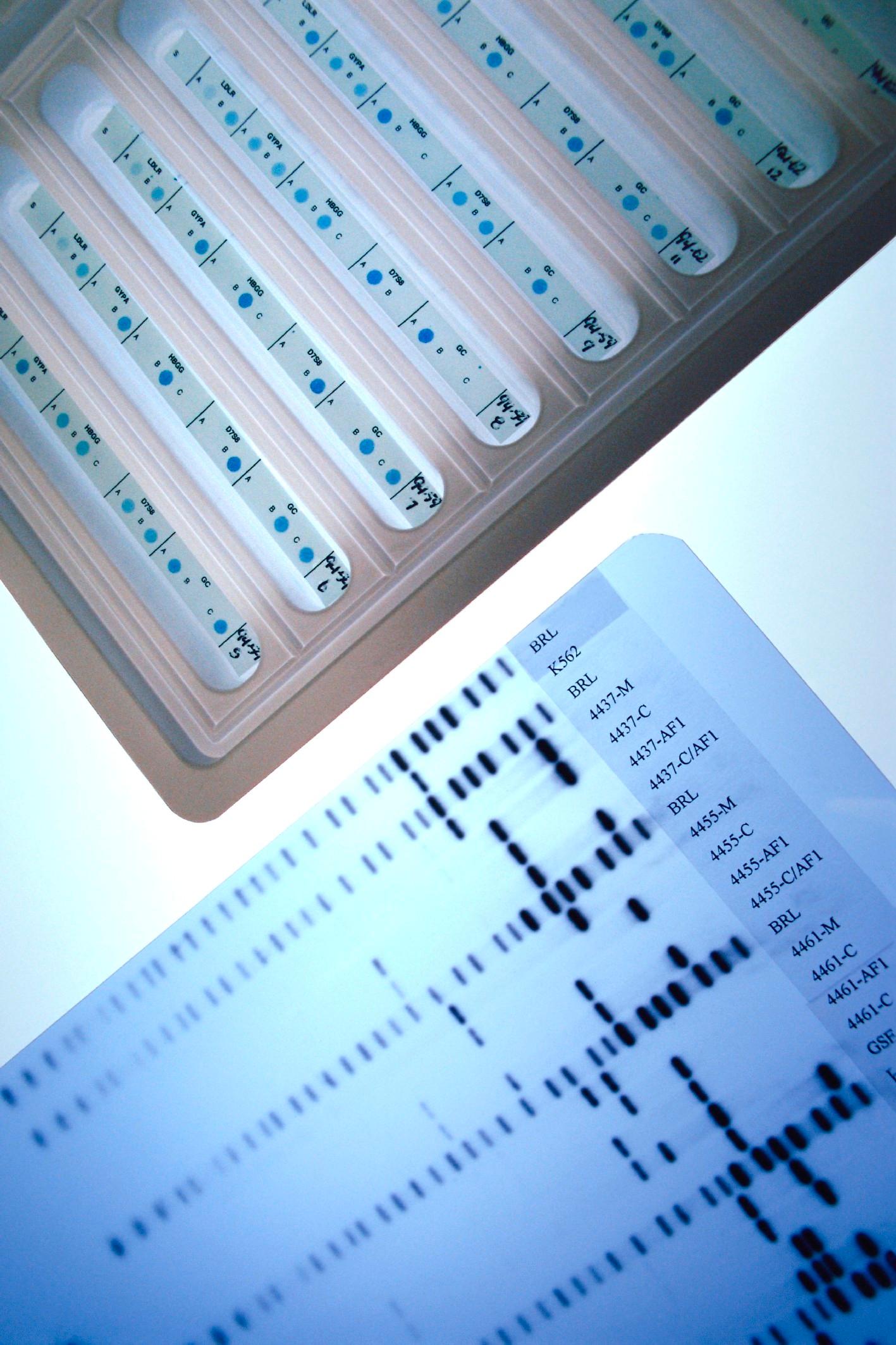

Digitisation is aided by breakthroughs in genetic sequencing. The estimated cost for sequencing an entire genome has dropped dramatically since the first full sequencing was completed in 2003. There has also been a significant increase in the number of variants in the human genomeExternal link related to human health that have been identified – from 62,00 in 2013 to 850,000 in 2018.

With this genetic information, pharma companies are shifting from the traditional way of treating cancer focused on tumour location to treating the mutation directly, offering more opportunities for precision.

The other 96%

One of the greatest benefits to digitisation is the potential to identify likely benefits develop drugs based on unique biomarkers of people who are not part of clinical trials – which is 96% of patients.

But some experts aren’t fully convinced of the equalizing power of precision (also called personalised medicine). In an article ahead of WEF, Patrick Courneya at the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and HospitalsExternal link and Michael Kanter at the Permanente Federation wrote: “Precision medicine will fall far short of its promise if the costs are so high that they make it unavailable to everyone.”

Another hurdle to overcome is the public’s acceptance of genetic testing, where the association with “designer babies” has ignited both ethical and legal debates.

In the age of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, there are concerns that all of this intimate personal health data could be misused. Lee’s colleague, Ron Park, who leads the commercial part of personalised medicine at Roche Pharmaceutical, says: “It is our obligation, from a trust perspective, to advocate for the highest standards of privacy. But we also need to be clear about benefits. At the end of the day, patients have to weigh the risks and benefits.”

Is tech the future of pharma?

New tech entrants to the pharma sector raise questions about how pharma will change tech or vice versa. Schneider envisions a day where companies like “Alibaba, Google, or IBM will launch drugs. It is big business and pharma has to adapt. I don’t know if it is a good or bad thing.”

Novartis Chairman Joerg Reinhardt doesn’t express the same level of concern about the emergence of tech. He told swissinfo.ch in a brief interview on the sidelines of WEF that “Amazon may enter the drug distribution market, but this is a small piece of the pharma business. Once drugs are on the market tech companies may take over, but I am not worried about tech companies entering pharma.”

More

Roche Chairman Christoph Franz on the future of pharma and tech

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

![The four-metre-long painting "Sonntag der Bergbauern" [Sunday of the Mountain Farmers, 1923-24/26] had to be removed by a crane from the German Chancellery in Berlin for the exhibition in Bern.](https://www.swissinfo.ch/content/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2025/12/01_Pressebild_KirchnerxKirchner.jpg?ver=cb688ed5)

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.