Locals blame Transocean and BP for oil spill

As the Swiss-based drilling contractor Transocean prepares to release its report into the Gulf of Mexico disaster, swissinfo.ch takes a stroll along the Florida coast.

Anger and suspicion are the main emotions one encounters in Pensacola, a small port in western Florida, where inhabitants feel that British oil giant BP and Transocean share responsibility for the catastrophe.

Life was turned upside down for locals in April, when the Deepwater Horizon rig owned by Transocean but leased to BP exploded and sank in the Gulf. The well was capped on July 15 and permanently blocked on Sunday after causing billions of dollars worth of environmental and economic damage to Gulf coast states.

David McCoy, a tanned student at the nearby naval base, goes swimming and surfing every day on the beach at Pensacola, despite posters warnings against doing that.

“I’m not concerned with water quality,” he told swissinfo.ch. “I don’t see anything bad floating around me.”

Amanda Traudt, a waitress in one of the region’s best restaurants which has an uninterrupted view of the ocean and the tubes trying to contain the oil on the surface, strongly disagrees.

“I’m not going to swim in that water, nor are any members of my family. It’s out of the question,” she said, adding that she gave birth to her youngest child as the oil starting leaking fifth months ago.

“We’ve seen less oil here than elsewhere, but it’s what you don’t see that’s going to harm us the most.”

No comment

Even if the well has been sealed and declared “effectively dead” by the US government, that doesn’t resolve the ecological and economic catastrophe that continues to affect the Gulf and its coastline.

And while Americans have BP in their sights, Transocean is not escaping its share of disgrace.

McCoy and Traudt might differ in that one has changed her behaviour and one hasn’t, but both agree that the Swiss-based company shares the blame and that the regulation of off-shore drilling needs to be tightened.

Aaron Viles, campaign director for the Gulf Restoration Network, adds: “It was BP’s decisions that set in motion this disaster, but Transocean will bear some responsibility and liability to help restore this region.”

Transocean declined to reply to swissinfo.ch’s questions. “We’re not doing any recorded interviews,” said communications director Guy Cantwell.

Devastated community

Pensacola is hundreds of kilometres from the site of the explosion and lives off tourism – but the beaches, hotels and restaurants are deserted.

“Once oil got here, it absolutely decimated the tourism business, which is Pensacola’s main resource,” Matthew Villmer, lawyer for oil spill victims in the Pensacola area, told swissinfo.ch.

“And even if oil never came on this beach or another one – even if all the oil has been cleaned up, the perception that there is an oil spill was enough to devastate our community.”

He added: “Among my clients, I have a surf shop owner, two fishermen, a seafood wholesaler, owners renting condos on the beach, rental booking agencies, property owners, even flowershops that supply beach weddings; it shows you how long-reaching the effects of the oil spill are on the economy.”

BP faces potential fines under several anti-pollution laws and recent increases in the estimate of how much oil leaked from the well suggest this could amount to a major liability.

Like his colleagues who are dealing with hundreds of complaints, Villmer’s first job is to try to get his clients reimbursed from the special compensation fund set up with the $20 billion (SFr19.7 billion) that BP has promised to pay.

However, he says that the special fund “is mistreating many clients who are indirect victims of the oil spill because the maximum payout to them is $12,000, regardless of what the damages are”.

Anger and suspicion

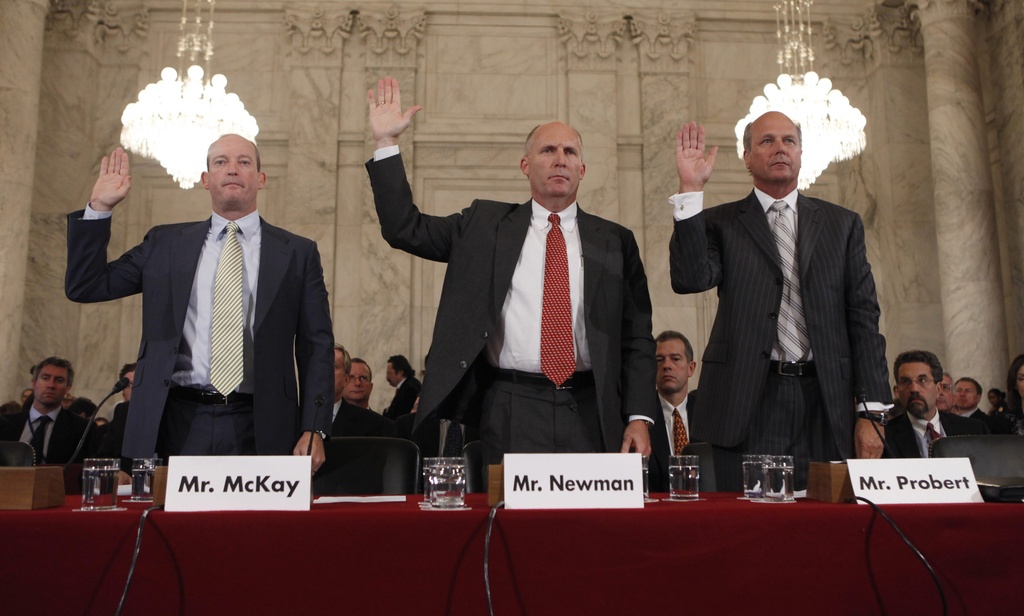

For its part, Transocean is set to publish its own investigation soon.

On September 8 a report by BP placed much of the blame for the worst crude spill in US history on the rig operator, claiming that “multiple companies” and mistakes were at the heart of the Deepwater Horizon blowout.

In response, Transocean accused BP of producing a “self-serving report that attempted to conceal the critical factor that set the stage for the [Gulf] incident: BP’s fatally flawed well design. In both its design and construction, BP made a series of cost-saving decisions that increased risk – in some cases, severely”.

In the absence of any responsibility being established by an independent inquest, notably that of Congress, complaints might as well be lodged with BP and Transocean equally.

“Until we know what happened, we have to file against those two companies so we’re sure to get compensation,” Villmer said.

He notes however that “in the weeks prior to the explosion, Transocean’s drill rig was due for serious maintenance. Whose decision was it to delay repairs? That needs to be determined.”

Anger is such among people along the coast that even federal inquests are met with suspicion.

“We don’t trust any of those investigations. We’re disappointed by the federal government response and by BP’s response,” said Aaron Viles.

“That said, we’ll look very closely at the Department of Justice report and the presidential commission’s report.”

On April 20, 2010, an explosion and fire killed 11 crew members and destroyed a Transocean-owned semisubmersible drilling rig called Deepwater Horizon, positioned about 50 miles southeast of Venice, Louisiana, in water nearly 5,000 feet deep.

The rig, one of the largest and most sophisticated in the world, had been under contract to BP, the London-based oil giant, since September 2007.

The Deepwater Horizon accident spewed thousands of barrels of oil a day into the Gulf of Mexico, and experts said it could become the largest oil spill in history.

Attempts at the weekend of May 8-9 to cap the well with a giant metal funnel failed.

BP has a new plan to block the well by ramming rubbish into it.

The Gulf of Mexico accounts for one-third of America’s domestic oil production and one-fourth of its natural gas. There are 90 exploratory rigs working there and about 3,500 oil-producing platforms.

Transocean is the world’s largest offshore drilling contractor.

Although it was established in the US, its headquarters have been in the Swiss town of Zug since 2008.

According to its website it has 138 mobile offshore drilling rigs and 20,000 employees world wide.

Its website describes its safety vision as: conducting its operations “in an incident-free workplace, all the time, everywhere”.

Its clients are global energy firms, national petroleum companies and independent contractors.

It constructs wells for both oil and gas all round the world: the Gulf of Mexico and eastern Canada, Brazil, the British and Norwegian sectors of the North Sea, West Africa, Asia, including Australia and India, the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, and the Mediterranean.

Shares in Transocean fell by 12 % on the Zurich stock exchange on Friday as a result of the oil spill.

Some experts say BP could ask Transocean, the owner of the rig, to help pay for the clean-up operations.

However, BP, as operator of the rig, has accepted responsibility and says it will compensate those who have suffered from the accident.

US President Obama has also said BP is ultimately responsible for the crisis.

(Translated from French by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.