Organ-harvesting claims spark controversy

Allegations by former war crimes prosecutor Carla Del Ponte of organ trafficking in Kosovo and Albania must be fully investigated, says a Swiss ex-parliamentarian.

In her new book, Del Ponte claims – based on what she describes as credible and eyewitness reports – that Kosovar Albanian guerrillas transported 300 Serbian prisoners to Albania where they were killed and their organs removed and trafficked.

Serbia and Russia are demanding a war crimes investigation into the accusations. The Kosovar government, now headed by the former guerrilla leader Hashim Thaci, dismisses the claims as untrue, and other officials and politicians have expressed scepticism.

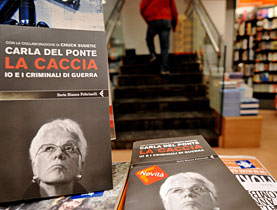

The allegations appeared in Del Ponte’s just published memoirs, “The Hunt: Me and War Criminals”, of her eight years as chief prosecutor for the international war crimes tribunal for former Yugoslavia, based in The Hague.

Ruth-Gaby Vermot-Mangold, a former Social Democrat parliamentarian who has investigated organ trafficking in Europe, told swissinfo it was crucial to shed light on the affair.

“We hear about these kind of trafficking stories but we have very few concrete cases,” said the human rights campaigner. “It’s important to go right to the end of the investigation for Kosovo, Serbia and for justice.”

New York-based Human Rights Watch has urged the Kosovo authorities to determine the veracity of the charges, saying there was “sufficiently grave evidence” in Del Ponte’s book.

But on Wednesday Olga Karvan, a spokeswoman for the Yugoslav war crimes tribunal, said UN investigators had found “no substantial evidence” to support the allegations.

And Florence Hartmann, Del Ponte’s former spokeswoman at the war crimes court, said the claims were “irresponsible”.

“Mixing up genres, juxtaposing crimes that have gone to trial, and these non-verified theories from witnesses she doesn’t know anything about, even their identity, encourages confusion between rumour and fact, and risks encouraging all kinds of revisionists,” she wrote in Wednesday’s French-language newspaper Le Temps.

A Swiss judge at the war crimes tribunal, Stefan Trechsel, also criticised Del Ponte’s book as unprofessional. He told Swiss television that she could not provide any proof to back her strong accusations.

Del Ponte, now Switzerland’s ambassador to Argentina, has been ordered to keep silent by the Swiss government.

House-clinic

In the book, published in Switzerland and Italy, Del Ponte writes that her investigators visited a house in a mountainous region of Albania. The clinic was reportedly being used to hold 300 Serbs captured by the Kosovo Liberation Army and transported across the border from Kosovo to Albania in June 1999.

According to witnesses – including one who said he had driven some of the organs to Tirana airport, and a team of unnamed journalists who investigated the allegations – the victims had had their kidneys removed before being killed and having other organs taken.

UN investigators examined the house and found medical equipment used in surgery and traces of blood, but were unable to determine if the blood was human.

Most of the victims were said to be Kosovo Serbs, but they also included women from Kosovo, Albania, Russia and Slavic countries.

Other sources claim the body parts were flown to Turkey, where they were transplanted into wealthy patients.

If the accusations prove to be true, Turkey’s role in the trade in organs is not surprising, said Vermot-Mangold.

“We have proof that people have their organs transplanted there and we know there is a market for organs, especially kidneys,” said the campaigner, who investigated the trade in body organs for the Council of Europe in 2003.

“Fabrications”

Del Ponte’s account is the first time such accusations have come from such an authoritative source. But some people are amazed that she should report five years after her investigators went to the alleged scene of the crime. Del Ponte says it proved impossible at the time to pursue a full investigation owing to insufficient evidence.

Kosovo Justice Minister Nekibe Kelmendi dismissed the allegations as “fabrications”.

“I have had four private meetings with Carla Del Ponte and she never once mentioned any such allegations,” she told Associated Press.

She criticized Del Ponte “for writing about issues that were not turned into official charges”.

Albania’s former prime minister, Pandeli Majko, who held the post during the Kosovo war and its aftermath, rejected Del Ponte’s claims as “strange stories, a fantasy”.

On Tuesday the Slovak foreign affairs minister, Jan Kubis, told the Council of Europe that Del Ponte’s allegations risked weakening the credibility of the UN tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

However, families of missing Serbs accuse the prosecutor of failing to take action even though they have provided the names of 300 people they say were involved in the kidnapping of Serbs.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley with agencies

Carla Del Ponte was born in 1947 in Bignasco, in the southern Swiss canton of Ticino. She studied international law in Bern, Geneva and Britain.

In 1981 she became Ticino’s chief prosecutor, where she became well known for her fight against money laundering, organised crime and gun running.

Del Ponte was Swiss federal prosecutor from 1994-9, to a mixed reception, with some accusing her of “activism”.

In 1999 the then UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan appointed her chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. During her eight years, she put Slobodan Milosevic in the dock, but he died before a verdict was reached. She was unable to capture the other two genocide suspects, Ratko Mladic and Radovan Karadzic.

She left this post at the end of 2007. In January she took up her new job as Swiss ambassador to Argentina.

The ICTY was established by Resolution 827 of the UN Security Council in May 1993.

Based in The Hague, it is the first international body for the prosecution of war crimes since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials held after the Second World War.

The tribunal has jurisdiction over individuals responsible for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity in the territory of former Yugoslavia after January 1, 1991.

Several thousand people, mostly Albanians, died in Kosovo’s 1998-1999 war. Some 1,500 Albanians and 500 Serbs and other nationalities are still missing.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.