Is digital democracy too risky, or the chance of a generation?

Long dormant, the issue of digital democracy is picking up speed in Switzerland. Two camps are facing off against each other: those who wish to adapt democratic instruments to the realities of the 21st century, and an alliance of traditionalists and security experts.

According to the The Economist’s Democracy IndexExternal link, Switzerland is one of the most democratic countries in the world. It is also a world leader when it comes to IT infrastructure. On the corresponding index of the World Economic Forum (WEF),External link Switzerland ranks eighth.

But Switzerland is struggling to combine technology and democratisation.

There are several reasons for this, some related to security. Even some of Switzerland’s youth parties are rallying behind this argument, which is astonishing because technological advances have now brought secure democratic procedures within reach.

Myth of village square democracy

The champions of traditionalism, who surface in all political camps, argue that online discussion is of inferior quality to discussions in natural settings. It is too anonymous, too fleeting, and the process is too simple if you can decide with just one mouse click, they argue.

More

Looking ahead to government by smartphone

Walter Thurnherr, the Swiss Federal Chancellor, recently posited at a Digital Dialog event in Biel-Bienne that different discussions tend to emerge while collecting signatures in a town square than while filling out an online form.

But traditionalists tend to overlook the fact that the younger generation is already predominantly developing political opinions on the internet. The US-based Pew Research Center found that during the 2016 US presidential election, more than 50% of 18-to-29-year-olds obtained their political information from websites, apps and social media. Cable television follows far behind at 12%.

Another study in the EU has shown that people who come into contact with political information online are more likely to participate in the political process. This is especially true when there are possibilities to participate online. Against this background, the imperative that democratic processes must remain analog seems somewhat nostalgic.

Security is debatable

But the security of polling and electoral processes is essential. For this reason, leading hacking experts warn of the dangers of e-voting. Gunnar Porada and Volker Birk, two such experts, recently raised the issue on the “Rundschau” programme on Swiss Public Television SRF.

However, two things were overlooked. First, 100% protection against electoral fraud does not exist. This is also the case when polling boxes and paper ballots are used.

A 2011 study in Germany revealed that electoral fraud is not an uncommon occurrence. Irregularities in elections, such as during the counting of votes and the transmission of results, are also a recurring issue in Switzerland.

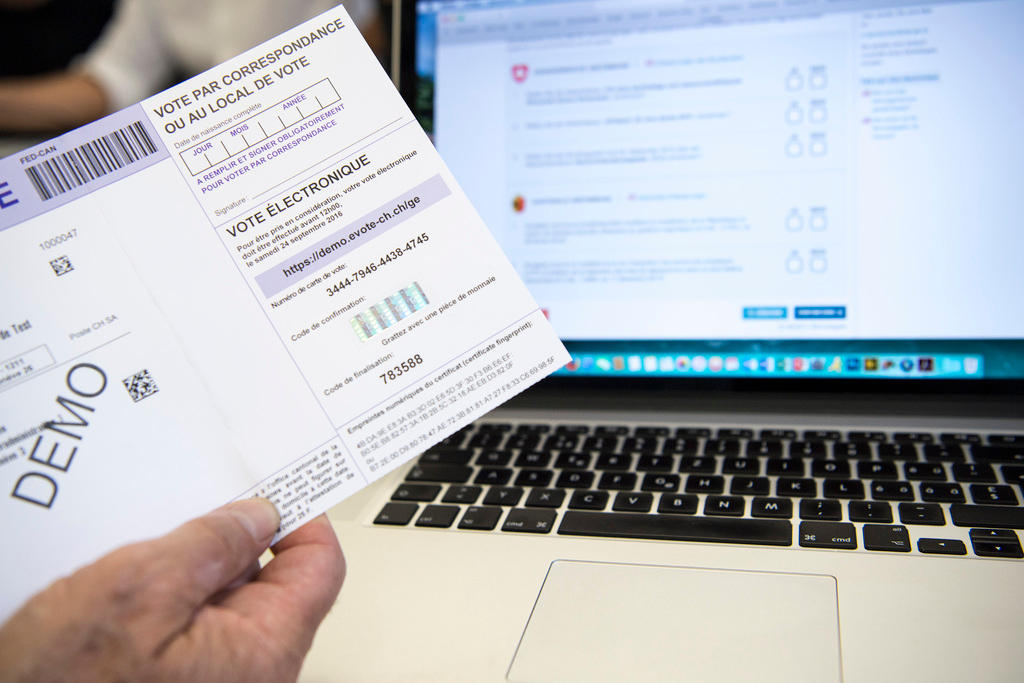

Second, it’s now possible to secure online voting using Blockchain technology (see box). Corresponding trials are already running in various countries, such as Ireland, Australia and the US.

The advocates of digitisation in voting are currently on the rise. Damian Müller, a member of the Swiss Senate, has submitted a motion which instructs the government to examine possible steps to digitise the entire democratic process.

It’s not just about enabling online referenda. Above all, it’s about making citizens aware of political issues online and via smartphones, fostering discussions, getting quick feedback from the people on political issues, and simplifying the collection of signatures. Abraham Bernstein, professor of computer science at the University of Zurich, has made the same argument.

Artificial intelligence vs. chat robots

A safe, substantial and playful online platform for referendums, elections and discussion should combine a few features to ensure healthy debates and to curb the tendency towards radicalisation. Professor Dirk Helbing of the Federal Technology Institute ETH Zurich recently summarised these features in an article in the Huffington PostExternal link. Online deliberation forums should include the following features:

They should be organised in a transparent and decentralised way to prevent manipulation and censorship.

They should be moderated by elected community moderators to facilitate fair and constructive discussions.

Artificial intelligence can be used to detect abnormal activity, such as exposing chat robots, ghostwriters or trolls. It can also sort and organise arguments and thus contribute to a balanced and clearly laid-out discussion.

Reputation systems could foster responsible behaviour and promote higher-quality contributions, and contributions from highly-rated authors.

Pokémon Go of politics?

Most importantly, however, such platforms need to be user-friendly and attractive. Imagine walking past a derelict site in your neighborhood. The city wants to renovate this empty area. Your smartphone makes you aware that your opinion on the matter is welcomed.

Using augmented reality, a digital extension of visible reality, you can now see the project ideas which have already been received on the platform and what they look like. With a swipe or click, you can then vote for your favourite project.

An even more playful approach would be to experiment with rewards in the form of points, in order to have a competition in a city or among friends, for example. The users would decide which data their circle of friends can see. Everything else remains anonymous.

Anyone who remembers the success of the online game Pokémon Go, which is based on augmented reality, will find it easy to understand the opportunities presented by playfully implementing digital democracy. It’s worth a try, especially when it comes to empowering the younger generation, because enjoying democracy is not a utopian vision.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.