Question hangs over Swiss links to apartheid

On the 20th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, Switzerland’s dalliances with South Africa’s apartheid regime have not yet been forgotten.

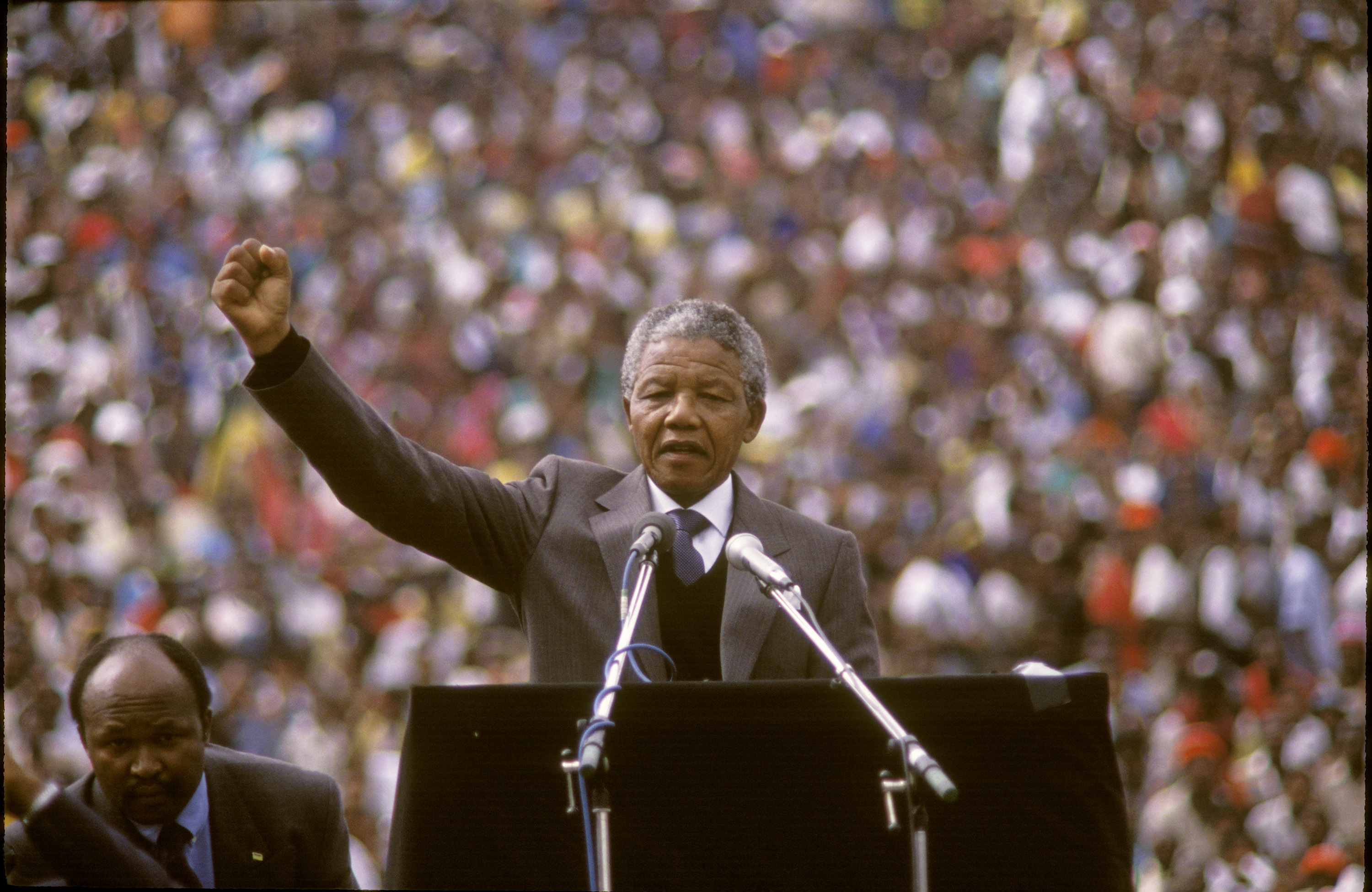

Nelson Mandela was freed on February 11, 1990 after 27 years in prison and went on to become the first black president of South Africa, to global applause.

Swiss-South African relations in the preceding years were the subject of a 2005 report by the Swiss National Science Foundation’s National Research Programme. Media and non-governmental organisations, commenting on the report, said that by and large freedom of commerce and industry had prevailed over human rights.

Although Switzerland condemned the Pretoria regime in 1968, imposed an arms embargo in 1963 and limited investment in South Africa in 1974 (two regulations that were bypassed later), private business continued to flourish in the country until the end of the 1980s.

And by looking the other way, Swiss political circles and the government were able to work closely with the regime: swapping military pilots, holding frequent meetings between secret services and even delivering equipment for six atomic bombs that Pretoria later confessed to have built.

Sandra Bott, who worked on the economic relations aspect of the national research project, dubbed “42+”, said there were “strong mutual interests between the two countries”.

The findings did not come as a complete shock to the researchers. “I had somewhat expected what we found,” she said.

What did surprise her was the importance that marketing South African gold had for Swiss banks. And similarly, the confirmation that federal authorities in 1968 had “erased” Switzerland from statistics published by the South African Central Bank on capital movements abroad.

“I nevertheless thought it was pretty crazy. It was the Swiss ambassador to Pretoria who, on behalf of the foreign ministry, called on the central bank to alter its records,” said Bott. “Thus, countries no longer appear by name but in categories such as the ‘dollar zone’ or ‘sterling area’. And Switzerland is in the ‘rest of Europe’.”

Access denied

There might well have been other surprises if the researchers had been able to carry out their work until the end.

But unlike those involved in the Bergier Commission on relations between Switzerland and Nazi Germany, historians of the programme 42+ saw their access to sources limited from the start of their mandate in 2001.

The government did not insist that companies operating in South Africa open their archives. And of course, they almost all refused to do so.

Since archives are normally only made available after a time lapse of 30 years, the historians were unable to consult any papers later than 1971. When they asked to be given access up to 1990, the opposite happened: on April 16, 2003 the government decided keep the archives secret not for 30 but for 40 years.

In support of its decision, Bern said there was a risk of class-action lawsuits against Swiss companies, which served as an acceptable explanation for Franz Blankart, Swiss secretary of state for foreign trade from 1986 to 1998.

“In the United States for example, there is always a risk of litigation against businessmen active at the time in South Africa or even against the confederation,” he said.

The Berne Declaration, an umbrella body of non-governmental oragnisations, has denounced “the way the government bowed to pressure from the Swiss Bankers Association and [Swiss Business Federation] economiesuisse”.

Ineffective sanctions

A key question remains: by failing to impose the UN sanctions and remaining a partner of the racist regime in Pretoria until the last possible moment, did Switzerland help prolong apartheid rule?

Like most economists, historians at the project are sceptical about the actual effectiveness of sanctions. The fact that Switzerland did not participate in sanctions “did not prolong apartheid, especially as the said sanctions were ineffective”, the project report states.

The Berne Declaration countered: “The report’s findings regarding the issue of sanctions are not supported, but contain exactly the kind of statements that are politically desired by and convenient for large banks.”

Blankart is more nuanced in his conclusion. “In 1992 I met the future President Mandela twice,” he said. “He confirmed that Switzerland’s non-participation in the sanctions had not bothered him. He needed an economy that worked and not a weakened economy.”

Marc-André Miserez, swissinfo.ch (Translated from French by Jessica Dacey)

1950 – The South African parliament votes in four laws establishing apartheid. At that time, Ciba (now Novartis), Roche, BBC (now ABB), UBS’s predecessor bank, and other large Swiss firms create subsidiaries in South Africa.

1956 – Swiss South African Association is created to serve like a chamber of commerce

1960 – March 21, police kill 69 black demonstrators. A general strike and brutal repression ensue. The ANC is banned.

1963 – The UN calls for an embargo on arms sales to South Africa. Switzerland imposes a ban on exports.

1964 – Mandela and other ANC leaders are sentenced to life imprisonment.

1968 – Switzerland condemns apartheid at UN Conference on Human Rights. Swiss banks create a purchasing pool for gold and Bern asks the Central Bank of South Africa to erase Switzerland from its statistics. By the late 1980s, Switzerland has bought SFr300 billion worth of gold from South Africa.

1974 – Bern caps Swiss investment in South Africa at SFr250 million a year (and SFr300 million from 1980). The limits are easily circumvented.

1976 – Soweto uprising sparks confrontation which leads to nearly 600 deaths.

1986 – Switzerland begins to support South African NGOs that defend human rights and democratisation, spending SFr45 million by 1994.

1990 – ANC ban lifted. Mandela is released on February 11. On June 8, he arrives in Switzerland and meets Foreign Minister René Felber.

1994 – April 27, the first general elections in South Africa. Landslide victory for the ANC. Mandela becomes the first black president of the country.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.