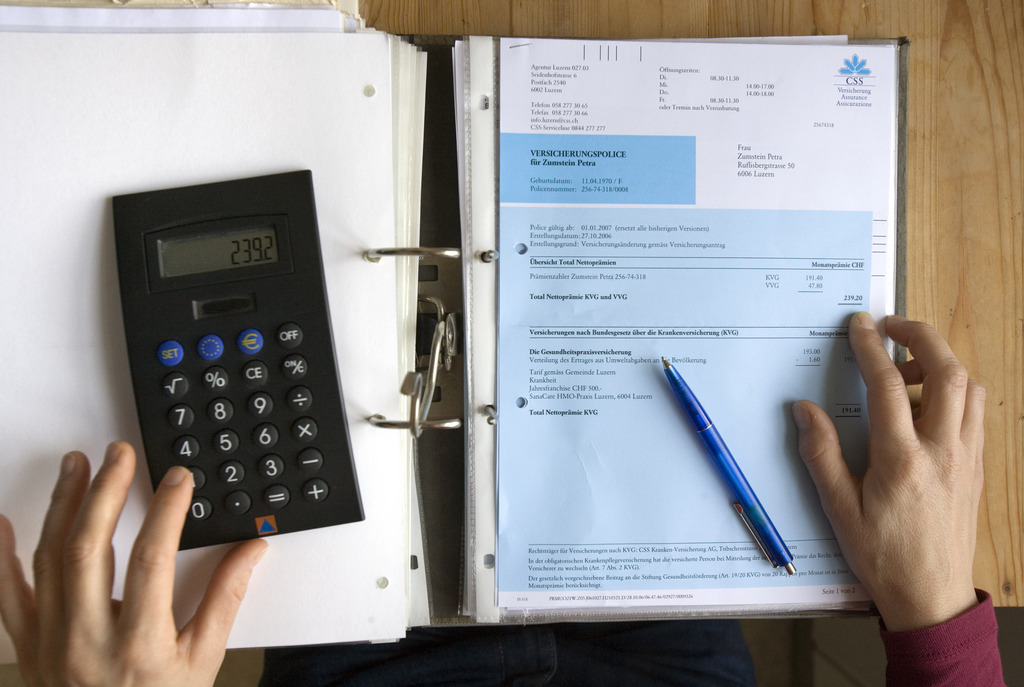

Seeking a political cure for rising health costs

Expensive health insurance is a given in Switzerland, and there are concerns that the latest proposals to help rein in costs could prove to be a cure worse than the disease. Voters will have the final word on whether a single fund is preferable to the choice they have now.

Health insurance is compulsory under Swiss law, and there are currently about 60 companies providing it. In 2014 or 2015 the initiative for public health insurance will be put to a nationwide vote, which if accepted will see current providers of basic cover replaced by a single public fund.

The initiative – supported by the centre-left Social Democrats and by the Greens as well as by patient and consumer organisations – would leave only supplemental insurance in the hands of private companies.

The government has rejected the proposal, stating that the current system, based on the principle of regulated competition between health insurers, has clear advantages.

But in February it put forward a counter-proposal of its own. Insurance companies would compete only on the basis of their services, while the practice of pursuing clients with favourable risk profiles would be limited.

A public fund, which would be responsible for the reinsurance of the most expensive patients would also be set up, limiting incentives for insurers to select clients based on risk profiles.

So far the counter-proposal has failed to gain any traction.

Representatives of the centre-right parties, most of whom are already against the initiative, also reject the government’s suggestions, because they consider them to be a first step towards the nationalisation of health insurance. Supporters of the initiative have on the other hand criticised the cabinet’s counter-proposal as half-hearted.

Health insurance is compulsory for all residents of Switzerland. Providers are legally obliged to offer basic cover to anyone who lives in the area they operate in.

Basic insurance covers diagnosis and treatment of a disease and its consequences.

Anyone who wants more than the basic cover can take out supplemental insurance. This includes, for example, complementary or alternative medical treatments, or greater comfort such as individual rooms during hospital stays.

Companies have the right to reject new applicants for supplemental insurance.

Clients pay monthly insurance premiums. The companies may set the amount in function of the age, health or sex of the client. The amount varies not only from company to company, but also from canton to canton.

Disagreement rife

The government cannot expect a lot of support from the cantons either. The conference of the 26 cantonal health directors, 16 of whom belong to rightwing and centre-right parties and ten to the centre-left and green camp, rejected the initiative and the counter-proposal during a plenary session on Thursday.

But this rejection is certainly not unanimous, if political beliefs are anything to go by.

Directors on the centre-right say that if there were a single centralised fund, people would lose the right to choose their insurer, and to swap companies if they are dissatisfied.

On the centre-left, supporters of the single insurance fund point to the extra administrative burden that arises from having to deal with so many different companies.

But stating that there is no real competition between providers fails to convince their opponents.

“I certainly think different companies provide different services,” Graubünden health director Christian Rathgeb, a centre-right Radical, told swissinfo.ch. “You can see this for example in polls on customer satisfaction.”

Nor does he think state insurance would be any more efficient – and in any case, administrative costs account for only a small fraction of the companies’ expenditure.

His counterpart from canton Vaud, Pierre-Yves Maillard, a member of the centre-left Social Democrats, disagrees.

“It there was only one insurance fund it would have an interest in prevention and coordinated care, because it would be responsible for the health costs of the entire population,” he explained.

As things are now, insurers want to be rid themselves of expensive clients, because they are a drag on profits, he maintains.

Rathgeb agrees that this is a problem, but one that should be dealt with by the supervisory authorities, by changing regulations on how risks are spread.

Next time lucky?

It is not the first time that the Social Democrats have tried to persuade Swiss voters to support a single insurance fund. The last attempt, in 2007, was rejected by 70 per cent of those who cast their vote.

Maillard thinks attitudes have since changed. He points out that German-speakers were overwhelmingly against it six years ago because they had the impression that French-speakers had higher health costs and they didn’t want to pay for them.

But since then, it has emerged that in two French-speaking cantons, Vaud and Geneva, as well as Zurich, policy holders had vastly overpaid for years, while premiums shot up in some German-speaking cantons to cover costs.

And under the system now being proposed, premiums would not be dependent on income, as they would have been had the 2007 proposal been accepted.

Whether voters are really ready to swallow the single insurance fund pill is still unclear. According to the 2012 Health Monitor of the GfS Bern research and polling institute, 40 per cent of those questioned were in favour of a change, while 45 per cent preferred to stick with the current system.

(Adapted from German by Julia Slater)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.