Turkey and Armenia sign landmark accord

Turkey and Armenia took a major diplomatic step toward normalising relations when the bitter rivals signed a landmark deal in Zurich on Saturday.

Representatives of Switzerland, Russia, the United States and Europe gathered to witness the historic agreement that will open borders and establish diplomatic ties, much to the anger of some Turks and Armenians worldwide.

The deal has taken six weeks of negotiations to reach. A delay came at the very last minute when the Armenians objected to statements the Turks planned to read after the ceremony.

US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton abruptly returned to her Zurich hotel to help defuse the situation. She later came back to the ceremony at Zurich University saying the problems were fixable. In the end, both sides agreed not to read statements.

About three hours later, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and his Armenian counterpart, Edouard Nalbandian, signed the Swiss-mediated deal shortly after 8pm local time. They stood up, shook hands to applause and exchanged hugs and handshakes with the other ministers.

Micheline Calmy-Rey, the Swiss foreign minister, praised both sides.

Broader context

The document has cleared the way toward reopening a common border Turkey closed 16 years ago while Armenia fought a war with Azerbaijan, a state with close ties to Turkey. The states will also exchange diplomats for the first time.

The Swiss Armenian Union said it recognised the “strategic necessity” to open the border and welcomed normalising relations.

Yet the deal’s larger significance extends far beyond the border, which could be opened in two months. Turkey hopes the accord will further its negations on joining the European Union. Armenia, poor and landlocked, yearns to move out of isolation.

Easing tensions in the area could help stablise the troubled Caucasus region and open an energy corridor to supply the West. The most optimistic expectations hope the deal will end a century of acrimony between Turks and Armenians that crosses religious and geopolitical boundaries.

Hurdles ahead

Swiss diplomats were instrumental in brokering the accord amid the complex and bitter rivals. Worldwide leaders like Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, Clinton and numerous European officials have backed the Swiss effort and attended the ceremony on Saturday.

Despite the broad spectrum of support, the deal still faces significant hurdles toward being put into force. Parliaments in both countries must pass it first.

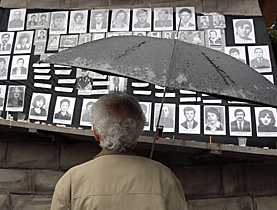

That could create problems for elected officials. Thousands of Armenian protestors have decried the conciliatory moves with Turkey and on Friday held demonstrations around the globe.

Armenians abroad – estimated at 5.7 million – outnumber the 3.2 million living in Armenia itself, one of the smallest of the ex-Soviet republics. Most live in Russia.

“Even if the documents are signed tomorrow, that will mark the beginning of our struggle against their ratification in parliament and their implementation,” protest organiser Kiro Manoian in Armenia told The Associated Press on Saturday.

Tensions are also prickly in Turkey, where nationalists have claimed the deal is undermining their country’s integrity and interests.

Between 1988 and 1994 Armenia and Azerbaijan fought for control of an enclave populated with Armenians in Azerbaijan called Nagorno-Karabakh. More than 30,000 people died, while hundreds of thousands became refugees. Turkey and Azerbaijan, with close cultural and linguistic ties, have considered themselves “one nation, two states” for nearly a century.

“If Armenia wants to repair relations, then it should end occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh, that’s it,” said Yilmaz Ates of Turkey’s Republican People’s Party.

Century of hate

Security surrounding the signing ceremony at Zurich University was tight on Saturday, when officers cordoned off buildings and stood poised on street corners for blocks. Access to the university and two museums was virtually impossible.

Much of the intense mistrust between the countries has spilled into other countries and stems from the last days of the Ottoman Empire, when as many as 1.5 million Armenians were killed by Turks. The killings have poisoned relations ever since. Armenians have called the massacre genocide, while Turkey has vehemently denied it.

The deal signed on Saturday only hinted at the killings in an effort to focus on establishing diplomatic ties. It calls for a panel to investigate “the historical dimension” of the hatred and establish “an impartial scientific examination of the historical records and archives to define the existing problems and formulate recommendations”.

The Geneva-based Swiss Armenian Union said it hoped the panel would bring Turkey closer to accepting responsibility for the killings and not provide a forum for denials.

swissinfo.ch and agencies

The first protocol sets out the principle of restoring diplomatic relations. It enshrines territorial integrity and the recognition of existing borders.

The second protocol deals with economic, technological, cultural and historic relationships between the two countries. It establishes a committee of experts to investigate the deaths of 1.5 million Armenians in 1915.

The status of Nagorno-Karabakh has been disputed since 1918, when Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent from the Russian empire.

Soviet rule was imposed in the south Caucasus in 1921, and predominantly Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh became an autonomous region within the Azeri Soviet republic.

In 1988, the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities demanded to be transferred to the Armenian republic. The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and Nagorno-Karabakh, in a referendum boycotted by most of the local Azeri population, declared independence.

Sporadic fighting between Armenians and Azerbaijanis erupted in war in 1991. Ethnic Armenian forces, backed by Armenia, drove back Azerbaijani forces and took control of Nagorno-Karabakh and districts surrounding it.

A ceasefire was signed in 1994, but there are frequent violations. The front line is monitored by a single representative of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe and five field assistants.

Turkey and Armenia are pursuing rapprochement after almost a century of animosity stemming from the First World War mass killings of Armenians by Ottoman Turks.

The neighbours have agreed accords on bilateral relations and opening their border, which Ankara closed in 1993 in solidarity with ally Azerbaijan.

Turkey had previously ruled out opening the border until Armenia made concessions on the territory.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.