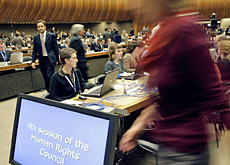

UN rights body shackled by slick diplomacy

The Geneva-based Human Rights Council will struggle to break free of its political straitjacket because it is made up of states, says an international law expert.

But speaking to swissinfo as the United Nations watchdog ended its fourth session on Friday, Andrew Clapham, a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, held out hope that progress could be made.

Negotiations on how the Geneva-based body will function have now entered the final straight. The 47-strong council, which stems from a Swiss initiative, is due to decide between now and June on a series of mechanisms and procedures.

Some are inherited from its widely discredited predecessor, the Human Rights Commission, such as investigations led by independent experts (special rapporteurs); others would be new instruments such as the universal periodic review, which would ensure regular monitoring of the human rights situation in every country.

The latest session ended with the council adopting a resolution expressing its concern over the situation in Darfur, but stopped short of criticising Sudan’s government over the atrocities.

swissinfo: Council members often come in for criticism for adopting a bloc mentality – North versus South, non-aligned countries versus the West. Is this justified?

Andrew Clapham: From time to time a country will take the floor of the council on behalf of one particular group. The European Union does this, which encourages African or Islamic countries to do the same. But it does not happen systematically.

In my experience, council members are working in blocs less and less on questions of the council’s procedures and mechanisms.

Blocs have formed predominantly on debates about Israel and to a lesser extent on Darfur. The council therefore does not seem to be overshadowed by a clash between blocs.

swissinfo: Perhaps it would be simpler to talk about a clash between democracies and dictatorships, in view of the pre-eminent role played by countries such as Cuba and Algeria?

A.C.: I don’t think so. Diplomats from these countries have a lot more experience than those from a lot of others. For example, Cuban diplomats in both Geneva and New York are very skilled and gifted. This know-how was gained during their diplomatic struggle against the embargo imposed by the United States.

If they are combative in the council, it is because of the mechanism arranged against them. If it wasn’t for the independent expert (Christine Chaney) charged with monitoring the situation in Cuba, they would surely be pursuing a different strategy.

swissinfo: Is there a link between the way the Security Council and the Human Rights Council operate?

A.C.: It’s clear that certain countries are trying to turn the Human Rights Council into a counterweight to the Security Council where they are not succeeding in getting their resolutions passed.

For example, when a resolution on Israel is vetoed in New York, the topic reappears in Geneva.

One would imagine that if attempts to reform the Security Council fail, then the Human Rights Council will further develop this role as a counterweight.

swissinfo: So the issue of human rights is once again at risk of becoming a political football?

A.C.: If you put governments at the heart of a human rights institution, they are inevitably going to express and defend their foreign policy. They are not going to look at the issue objectively, like experts or judges. Therefore this issue will always be politicised.

This is the reason why I hope independent experts will be allowed to take part in the universal periodic review to guarantee that this mechanism has a certain amount of objectivity. If successful, we will have an instrument for examining the human rights situation everywhere in the world for the first time since the creation of the United Nations.

swissinfo-interview: Frédéric Burnand in Geneva

Andrew Clapham is a professor of public international law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva.

He is also director designate of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, which is due to open in October 2007.

The council began its work in June last year.

It meets at least three times a year for a minimum of ten weeks.

It can call emergency sessions to respond to crises.

Switzerland was elected to the council with a three-year mandate on May 9 last year.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.