Democracy in 2016: all’s well that ends well

As a dramatic year for elections and referendums around the world comes to an end, there is little sign of “democracy fatigue”. Indeed, high turnouts in Austria and Italy show that direct democracy is in rude health.

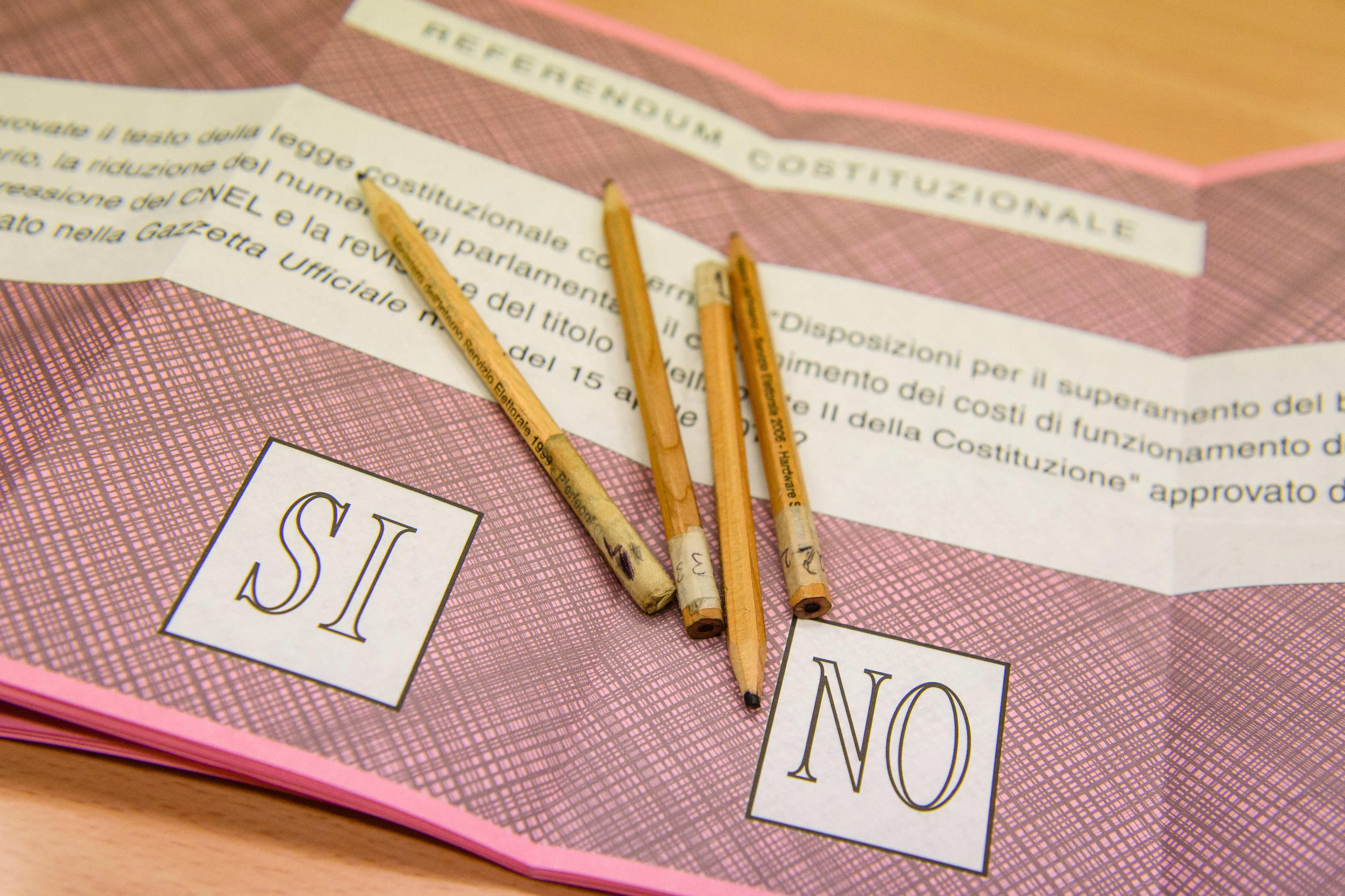

December 4, 2016, was really something: voters in Austria chose – at the third attempt – their head of state, while Italians rejected the biggest constitutional reforms for decades. Turnout in both European countries reached record levels: 68.5% in Italy and 74.1% in Austria.

Both figures are impressive. Earlier in the year, Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, who resigned immediately after the defeat, had scored a victory by urging the public to boycott a referendum on environmental policy backed by opposition parties. He did this because in Italy at least 50% of the electorate has to vote for referendums to be valid. In spring, more than half of voters stayed at home.

#Dear Democracy

This text is part of #DearDemocracy, a platform on direct democracy issues, by swissinfo.ch.

In Austria, the election of the largely ceremonial role of president turned into an administrative and legal fiasco full of appeals, repeats and voting envelopes that wouldn’t seal properly. Despite all this, turnout on December 4 exceeded that in the first and second attempts: at the beginning of May it was 68.5%; at the beginning of June 72.7%.

Varying results

But the political engagement of the Italians and Austrians is far from unique.

Around the world more people have got involved in politics democratically during 2016 than ever before. And in most cases they reached decisions that were not as irrational and short-sighted as opinion leaders would have us believe.

It began in January with the historic swearing in of the first female president of Taiwan and the success of democratic powers in the East Asian island state.

The end of February saw a hard-fought initiative in Switzerland to automatically deport foreigners who commit certain crimes. Here, too, turnout of 64% was above average. Six out of ten voters rejected the initiative.

And so on. The countless votes throughout 2016 might have produced a real mixture of results from a global and party political point of view, but the basic lesson is that plebiscites and direct democracy are two different kettles of fish.

Political miscalculations

What initially sounds somewhat dry and abstract can be neatly explained by four popular votes from the past year: four heads of states who tried to strengthen their grip on power via plebiscites, that is, public referendums decreed from the top.

The surprise was that all four paid the penalty at the polls. First off was June’s Brexit referendum in Britain, in which 52% of voters said they wanted Britain to leave the European Union. Then there was the question at the beginning of October of Hungary tightening its refugee policy: turnout of only 40% meant the vote wasn’t valid.

More

Media: Renzi’s ‘foolish gamble’ backfires

At the same time, 50.2% of voters in Colombia rejected a peace treaty with the Farc rebels. The rejection of Renzi’s reforms in Italy by almost 60% of voters is the grand finale.

In all four cases the leaders miscalculated, overestimating their own power. The consequences, however, have been different.

While David Cameron and Matteo Renzi resigned immediately, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán holds democracy is such little esteem that he celebrated the failed referendum as a “great success” for his government.

In Colombia, President Juan Manuel Santos let the failed peace treaty be legitimised belatedly by the Norwegian Nobel Prize committee – he will accept the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo on Saturday. Although Santos revised the treaty, he decided against letting the public have another say; instead, he let parliament ratify it.

Rays of sun

The failures were in some cases very painful. The defeat in Italy could even cause difficulties for the entire EU given that Italy is the third-largest economy in the eurozone.

As a result, it’s possible that a view of great significance for democracy could gain acceptance: namely, plebiscites are instruments that are loved by authoritarian rulers (and their parties) but they should be categorically avoided in modern representative democracies.

The reason for this is that plebiscites are designed for one-sided power increases, they are easy to manipulate and ultimately they challenge important foundations of modern democracy such as the rule of law, the separation of powers and the protection of minorities.

This is also part of the reason why many Brits, Hungarians, Colombians and Italians showed their governments the red card. But renouncing plebiscites doesn’t mean renouncing referendums and other process of direct democracy.

On the contrary, there is a strong case that in modern representative democracies it is necessary to have extended possibilities for citizens to have their say on institutional issues also between elections. Citizen-friendly laws for initiatives and referendums would result in important issues being placed on the political agenda and decisions being taken, thus helping to make our representative democracies a bit more representative.

If we look back on 2016 through democratic glasses, it certainly appears dramatic, loud and full of conflict. But peering closer at the record number of elections and referendums around the world ought to provide rays of sun between all the dark clouds.

More democracy is possible. But we must not only want it; we must also do something for it every day.

(Translated from German by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.