Why the Swiss accepted Tibetans with open arms

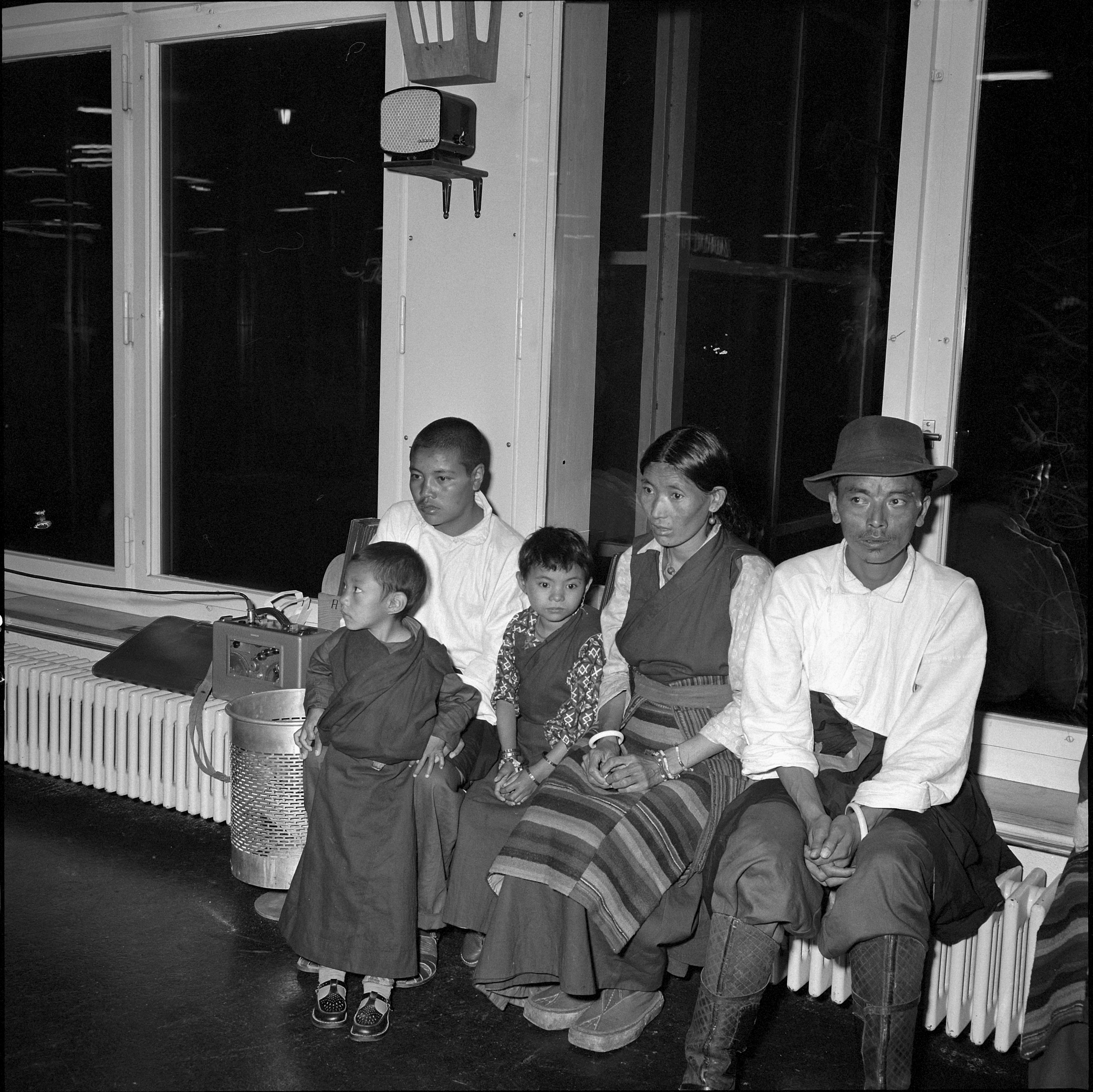

When Tibetan refugees traded the Himalayas for the Swiss Alps half a century ago and against the backdrop of the Cold War, they found a warm welcome.

Perhaps it was their connection to the mountains, explains the head of Switzerland’s refugee agency, or a sympathy with the underdog. But Switzerland has not always welcomed outsiders with the same enthusiasm.

Beat Meiner explains to swissinfo.ch how political factors both inside and outside Switzerland have played a role over the years in determining who are the wanted and who the unwanted.

swissinfo.ch: Why did the Swiss so closely identify with the Tibetans after their country was annexed by China in 1960?

Beat Meiner: A positive identification with victims was certainly a central reason for the admission of refugees. With the Tibetan refugees, there was a focus on both a political and an imaginary identification. China was under Communist rule and a Goliath compared with Tibet.

That the Tibetans were a “mountain people like the Swiss” was the basis for this imaginary identification. A myth because in reality, we are like the Tibetans.

Anti-communist sentiment in Switzerland, solidarity with the weak and an expected economic gain were also the basis for the political sympathy for the Hungarian refugees after the suppression of the uprising of 1956, and for Czech refugees after the 1968 Prague Spring.

The media also played an important role. The positive coverage was one reason for the huge interest and the willingness of the Swiss people to help the refugees.

swissinfo.ch: The warm reception to the Tibetan refugees came at the beginning of the 1960s along with an increasing fear of foreign infiltration, which in 1970 culminated in the Schwarzenbach initiative. How was that possible?

B.M.: In addition to sympathy for specific groups like the Tibetans, there was always the same antipathy or fear of other groups that seemed less close, or that seemed like direct competitors.

There was a lot of help in Switzerland for the refugees from Indo-China after the Vietnam War, for example. At the time, the Swiss Refugee Council received numerous phone calls from Swiss citizens who wanted to know when the refugees would arrive.

Not so for the followers of the socialist Salvador Allende, who fled Chile following his overthrow by Pinochet in 1973. They were very difficult to find hosts for in Switzerland. They were regarded as political opponents of the Swiss bourgeoisie.

The Jewish refugees from the East who arrived in the 1920s had a hard time and were regarded as backward and difficult to integrate. There was even talk of an imminent “Judaization” of Switzerland.

Even today’s refugees, mostly from Asia and Africa, alarm the Swiss because they are foreign and poor. In the current debate over refugees, we have gone to the absolute. “We cannot solve the problems of the world and we cannot take all of it in,” is the argument.

swissinfo.ch: To what extent did the start-up financial bonus for Tibetan refugees help with integration?

B.M.: In comparison for example with the so-called boat people from Indo-China, we operated different integration policies for the Tibetans.

While the Tibetans were housed in communities, they were assisted with preserving their Tibetan culture and a Buddhist monastery was built in Rikon. This was not the case for refugees from Indo-China, with the consequence that those refugees had much greater difficulty integrating.

It also shows that the current discourse about integration is completely backwards. Politicians try to outdo each other these days with repressive ideas about asylum seekers should be made like us, or otherwise punished.

For integration, it is important that one’s culture is not denied. On the contrary, refugees should continue their traditions.

swissinfo.ch: How do you view the current policy of the government towards Tibet?

B.M.: Relations with China have changed dramatically over the past 50 years. Nobody wants an economic fight with China these days.

As for refugees from Tibet, there are still single asylum seekers today but they regularly receive provisional refugee status, which compared with those previously admitted, puts them at a disadvantage.

swissinfo.ch: What impact has the inclusion of Tibetan refugees had on Swiss asylum policy?

B.M.: The inclusion of the Tibetan refugees, as well as the Hungarians and Czechs, has a strong symbolic value. So we should remember that despite gloomy chapters such as the Second World War, the people of Switzerland have a long tradition of protecting refugees.

The tradition goes back to the large number of Huguenot refugees in the 16th and 17th centuries.

It is regrettable that the 1995 refugee quota, launched while Tibetan refugees were arriving in Switzerland, has not been lifted. This is different from the EU, where the resettlement of refugees is becoming increasingly important.

Corine Buchser, swissinfo.ch (Adapted from German by Justin Häne)

A proposal by far-right politician James Schwarzenbach would have limited foreign workers in Switzerland to 10%.

The initiative on “excess of foreigners” would have deported up to 300,000 foreigners over four years.

It was put to a national vote in 1970, with a record turnout of 75% and defeated by a 55-45% margin.

Schwarzenbach’s party, the Republican Party of Switzerland, was a split off from the National Action, another far-right party. The two merged again in 1990, forming the Swiss Democrats.

That party is nearly defunct.

Schwarzenbach died in 1994.

The Dalai Lama’s most recent visit to Switzerland lasts from April 5-11.

He will take part in a rally for Tibet solidarity at Zurich’s Münsterhof on April 11 where he will thank the Swiss for 50 years of support.

Foreign Minister Micheline-Calmy Rey said in mid-March she would not meet the Dalai Lama due to scheduling reasons. The two have met four times over the last several years.

The Swiss-Tibetan Friendship Society criticised the lack of a meeting as “politically suspect” and blamed political pressure from Beijing.

The Dalai Lama on Thursday met with Pascale Bruderer, speaker of the House of Representatives.

On October 7, 1950, the Chinese under Mao Zedong invaded Tibet.

A week after a failed bloody uprising in 1959, the 24-year-old Dalai Lama crossed the snowy Himalayas into India, followed by around 80,000 Tibetans.

The first refugees arrived in Switzerland in 1960, at the Pestalozzi Children’s Village in Trogen.

In 1963, Switzerland allowed in 1,000 Tibetan refugees. They were the country’s first non-European refugees.

The 4,000 Tibetans in Switzerland today make up the largest Tibetan exile community in Europe.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.