Switzerland and its colonists

Switzerland had no colonies – yet some Swiss worked hand in hand with the colonial powers and profited from their seizure of land and resources on other continents.

Around 1800, learned European men were likely to describe the Swiss as “half- savages” who reminded them of encounters with “unlettered tribes on peaceful shores”. To them, the Swiss were still living in a state of nature. The Swiss have since turned this distorted picture to their own advantage. Today, no yoghurt advertisement or tourism campaign can do without exotic images of Swiss as “noble savages” up in the Alps. This kind of self-representation even crops up from time to time in the rhetoric of politicians who tell us that Switzerland is in danger of becoming a colony of the European Union.

More

How Switzerland profited from colonialism

Yet throughout their modern history the Swiss usually took the side of the colonisers rather than the colonised. It is true that Switzerland as a nation-state did not engage in imperialism, and conquered no colonial territories. Attempts to found great economic empires like the East India Company failed.

But it was part and parcel of colonialism to believe that the peoples in colonised lands were inferior to white Europeans. And in 19th-century Switzerland this was definitely part of the prevailing framework of assumptions about the world.

Generations of Swiss grew up with tales of “half-witted negroes”, travellers’ accounts of naïve, child-like savages, and advertising where the colonised were at best a decorative backdrop for colonial products. This thinking affects the country even today.

More

Bands and biscuits spark debate over racism and culture

Swiss soldiers in the colonies

The problem of Switzerland’s historical involvement in colonialism goes beyond controversies about derogatory names or statues. At times the Swiss were actually fighting as soldiers in the colonies.

In 1800, when black slaves in present-day Haiti on the island of Hispaniola rose in revolt against their French colonial masters, Napoleon sent 600 Swiss troops to fight them. France was able to draw on these mercenaries thanks to an agreement with the Helvetic Republic. This was by no means an exception; even after the modern federal republic was founded in 1848, Swiss defied the law to fight for colonial powers as mercenaries. They could look forward to considerable earnings as long as they didn’t die of tropical diseases.

More

Swiss mercenaries helped spread colonialism in faraway lands

Slave-trading Swiss

However, the big money from the colonies did not go to the mercenaries, who mostly came from impoverished families and saw it as a great adventure to enlist in Dutch or French service. Instead, trade was the moneymaker, be it in goods or human beings from the colonies.

One of the worst kinds of Swiss involvement with colonialism was that of the slave trade. Swiss individuals and companies made money out of slavery as investors and traders, organising slave-hunting expeditions, buying and selling people as slaves, and, as as slave owners, running great plantations which they often proudly called “colonies”.

As a result, quite a few famous Swiss names have started to look bad in recent years. The family of Alfred Escher, a major figure in the development of modern Switzerland, came under a cloud when it became known that it had a plantation run with slave labour. In Sacramento, California, this past June, demonstrators pulled down a statue of General John Sutter. The Swiss native son, who hailed from the Basel area, at one time ranked as a hero of the Wild West until historians revealed that he had dealt in child slavery.

List of slavery figures

The organisation CooperaxionExternal link has compiled a list of Swiss slave traders and owners, as well as Swiss who campaigned against slavery.

According to author Hans Fässler, by the 18th century, Switzerland had imported more cotton than England. He points out that the slave trade itself was a key industry without which production of many goods would not have been feasible. To put it bluntly, without cotton picked by slaves, the development of the Swiss textile industry would not have happened.

One sector of this industry is known to have profited directly from the slave trade: production of what were known as “Indiennes” textiles. These were produced for the European market, but also used as a barter item for the three-way trading system. The patterns were often designed to appeal to the slave-dealers who exchanged people for luxury goods.

More

The Swiss textile industry’s unsavoury past

In 1815, an advertisement from a Swiss textile firm read like this: “Favre, Petitpierre & Company begs all outfitters of slave and colonial ships to take note that the company’s busy workshops produce and supply all goods needed for barter trade with blacks, such as Indiennes and kerchiefs.”

Colonialism after slavery

After the slave trade was outlawed in the US, the textile industry worldwide went through a raw materials crisis – and India’s cotton market became more attractive. This niche was soon exploited by the Swiss firm Volkart, which had been working out of India since 1851 and had specialised in the trade in Indian raw cotton. The British controlled production: Indian peasants were forced to grow cotton instead of food crops. Through their close collaboration with the British, Volkart soon controlled a tenth of all Indian cotton exports used in Europe’s textile factories.

Another organisation that managed to come out a winner from the crisis caused by the end of slavery was the Basel Mission, the large Protestant missionary society based in Basel. Supported by the same Basel families that had previously invested in the slave trade, the Mission devised a new business model: it converted “heathens” in India to Christianity. These new converts were ostracised by their own people, so the Mission employed them in its textile workshops. One missionary described how the model worked in 1860:

“When people want to convert from paganism to Christ … we provide them shelter at the mission settlement and give them an occupation whereby they can earn their daily bread, be it in agriculture or some other trade. This is called colonisation.”

More

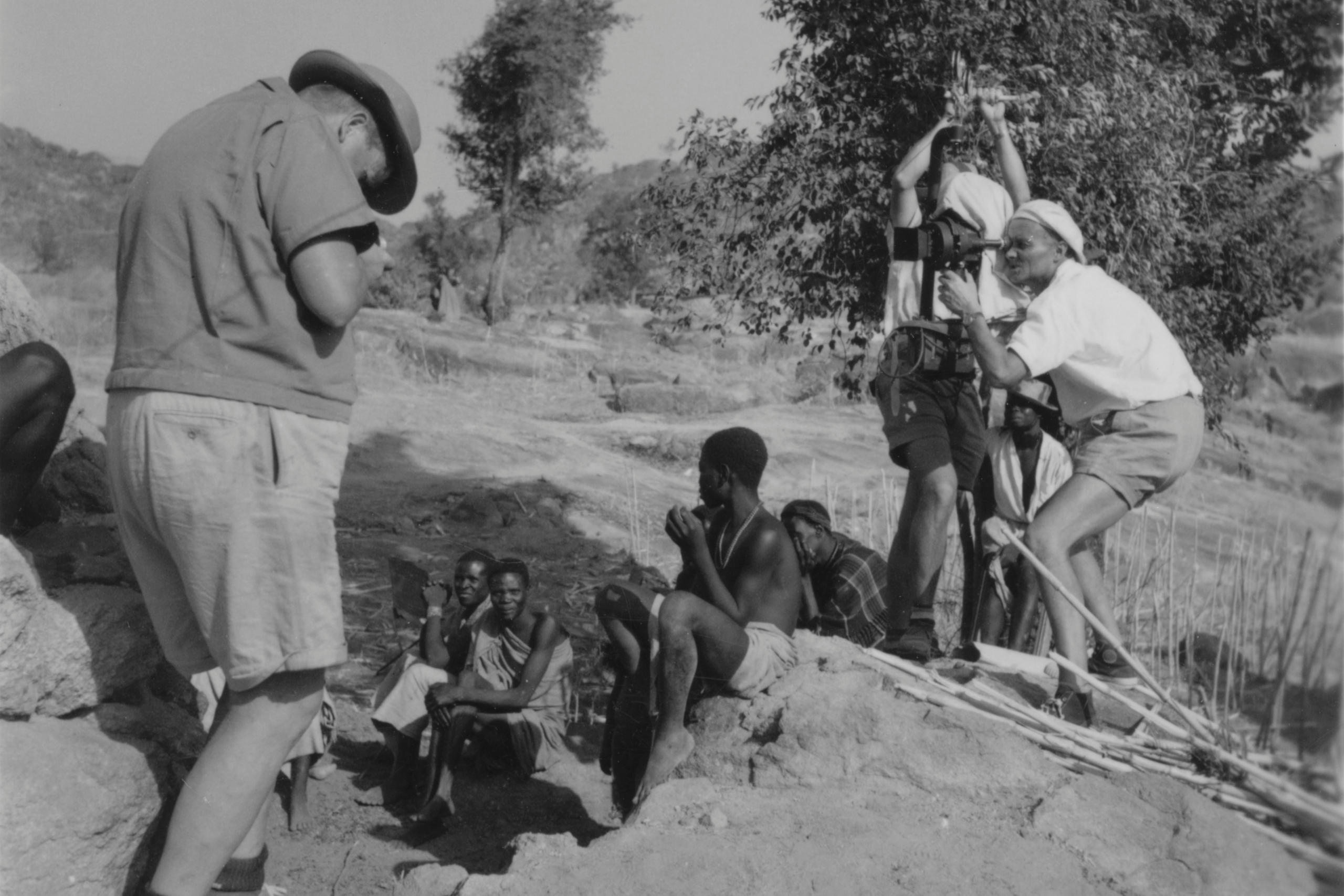

How René Gardi shaped Swiss views of Africa

Another part of colonialism is exploiting asymmetrical power relations to the economic advantage of the colonists. The 19th-century Swiss republic left the search for profit in the colonies entirely to private initiative. Parliamentary proposals for the federal government to provide a greater incentive for “emigration and colonisation” were defeated. The view of the federal government was: first, a landlocked country cannot colonise, and second, the government would be taking on a responsibility it would be unable to fulfil. Interestingly, these proposals in the 1860s came from the Radical Democrats, who advocated social reform and promoted stronger direct democracy mechanisms to contain the power of the establishment. These proponents of colonialism saw themselves as advocates for emigrants fleeing poverty and hunger in Switzerland itself.

Switzerland’s policy on emigration evolved over the course of the 19th century. In the early years of the century, the colonies were regarded as a place for people to go who could not be provided for at home. Later they were seen more and more as the basis of a new global network: the colonies gave young entrepreneurs a chance.

Those who took up this challenge enjoyed the same privileges as the citizens of the European colonial powers – they were simply colonists without an empire of their own.

In 1861, German economist Arwed Emminghaus expressed admiration for this strategy of “long-distance trading relations” on the part of Switzerland. He saw it as a variation on the imperial expansion policies of the colonial powers. “No expensive fleet is required, no expensive bureaucracy, no war or conquest,” he pointed out. “The world can be dominated in the most peaceful and simple way.”

Sources (in German)

- Andreas Zangger: Koloniale Schweiz. Ein Stück Globalgeschichte zwischen Europa und Südostasien (1860-1930). Berlin 2011.

- Lea Haller: Transithandel: Geld- und Warenströme im globalen Kapitalismus. Frankfurt am Main 2019.

- Patricia Purtschert, Barbara Lüthi, Francesca (Hg.): Postkoloniale Schweiz: Formen und Folgen eines Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien

- Thomas David, Bouda Etemad, Janick Marina Schaufelbuehl: Schwarze Geschäfte. Die Beteiligung von Schweizern an Sklaverei und Sklavenhandel im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Zürich 2005.

- Hans Fässler: Reise in schwarz-weiss: Schweizer Ortstermine in Sachen Sklaverei. Zürich 2005.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative