Switzerland gears up to place robots in classrooms

Covid-19 has accelerated the transition to online teaching, raising questions about the role of robots in classrooms. Switzerland is rolling out its own robot learning programs, but it’s still a long way off before they will replace teachers.

“Hi everyone, I’m Lexi”, a humanoid robot greets a full house at the University of St Gallen. Sabine Seufert, Professor of management of educational innovations at the University of St Gallen, first used the robot on a trial basis in her lectures in 2019. Equipped with artificial intelligence, “Lexi” operates like a chatbot and can carry out simple auxiliary tasks such as a Google search. Today, the University is researching other ways in which the robot can be put to effective use in classes.

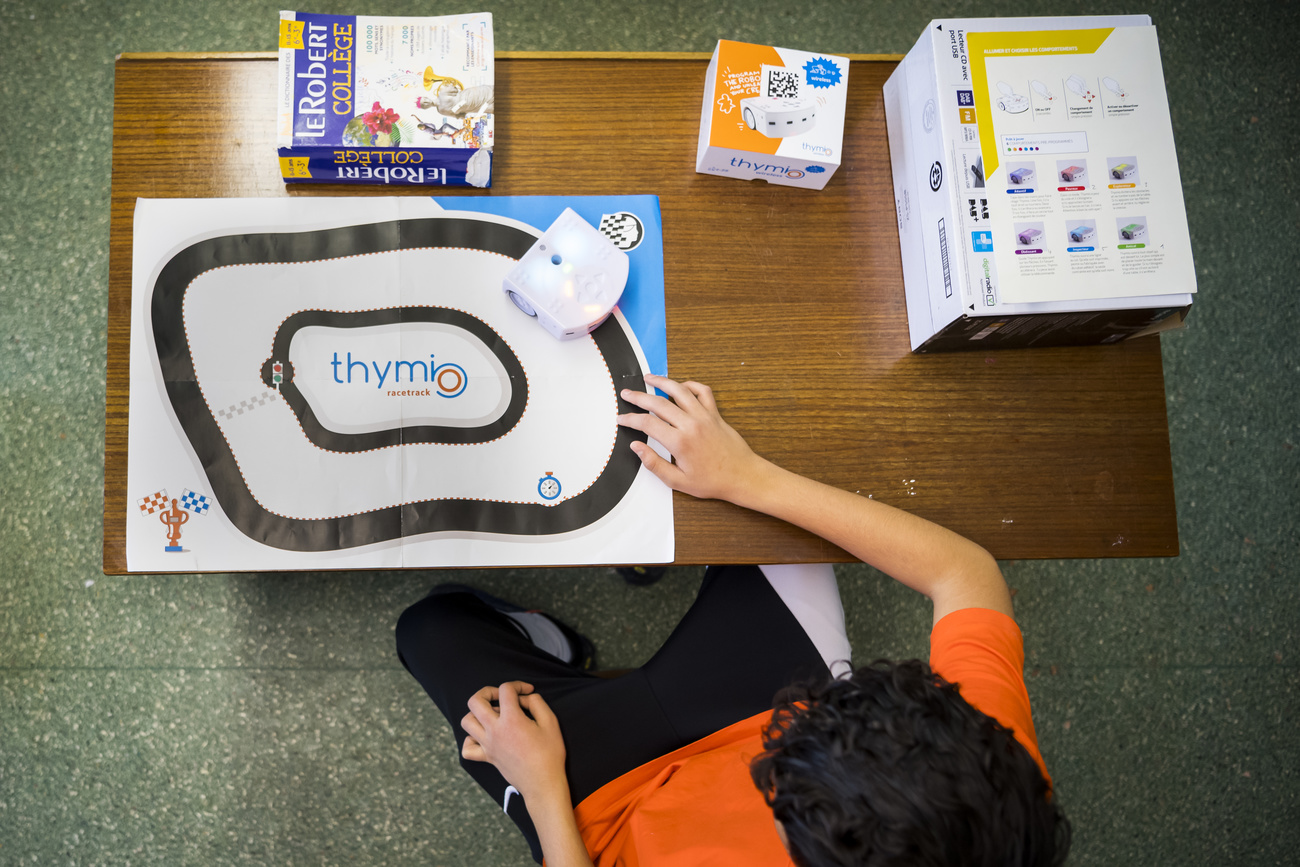

In school classrooms around Switzerland another robot is slowly making its entrance. “Thymio” is a small white box on wheels developed by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL). Its main advantage is that it can teach computer programming in a simple way to school children. Easy to program, the children can see immediate results. They can teach the robot for instance how to draw on command.

Robots like “Lexi” and “Thymio” are at the forefront of the digital transformation under way in schoolrooms and universities in Switzerland today. The Covid-19 pandemic coupled with forced distance-learning decreed in many schools and universities, are accelerating this technological transition.

This raises many questions about the future of teaching. What is the potential of these teaching and learning aids? And are schools and universities ready for this technological shift? How will this redefine the roles of teachers?

Switzerland has already gone a long way in developing learning with robots, according to Francesco Mondada, co-head of the educational robotics group at the National Centre of Competence in Research Robotics. One of the examples of Swiss-developed technology is the robot Thymio.

However, a closer look at what is happening elsewhere, shows that Switzerland is not in the lead compared with some of its neighbours. Seufert estimates that it will be ten to 15 years before robots will effectively be used in teaching. Currently the robots are just executing small tasks; technology still has to develop further for them to become real actors in education.

In the field of distance learning, meanwhile, the researcher sees greater potential for the use of intelligent chatbots, like those already found on the websites of banks and insurance companies. As classes increasingly take place online, bots would mean no physical presence of a teacher. The chatbots could help ease workload of the teachers for practical and repetitive tasks and give guidance to students.

Seufert is convinced that using a chatbot as a tutor would be particularly helpful in the teaching of languages for instance, where a lot of repetition is needed. “Today, teachers are completely overwhelmed, as they have 20 to 25 students to a class,” she explained.

More

Robots in schools: new teaching methods on the horizon?

Many schools are not ready

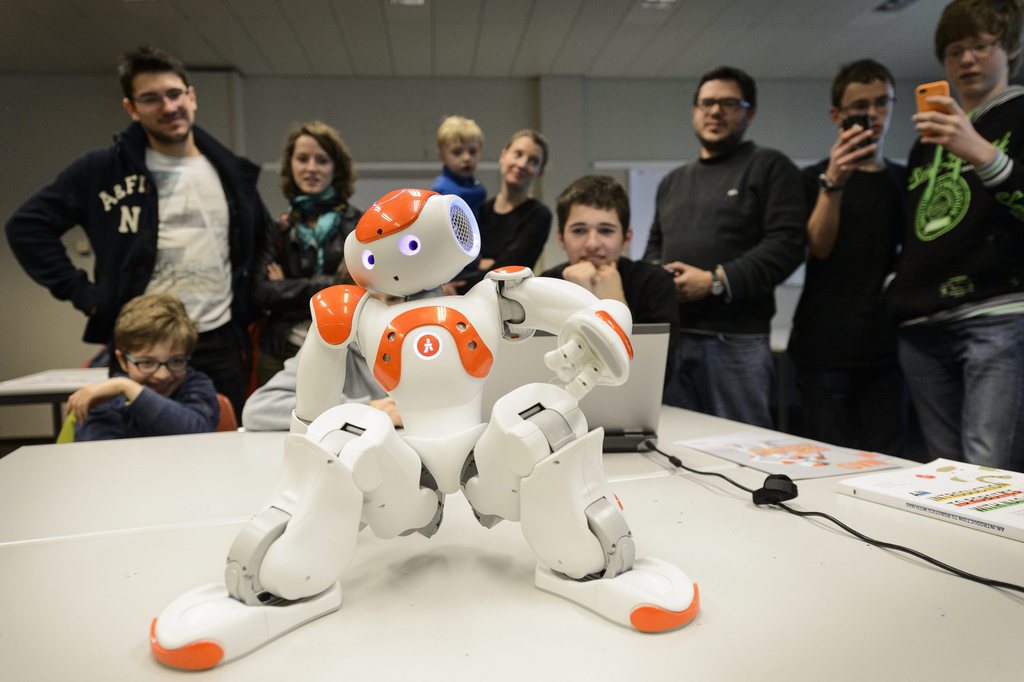

“A robot has the potential to disrupt the educational form of the classical class and to raise a lot of interest. It can bring a new dynamic into the class,” Mondada added. The professor also teaches at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) and heads its Centre for Learning Sciences (LEARN).

Other countries, meanwhile, are much more advanced in terms of actual use. For several years now, France has included robots as a tool in some school textbooks and Computer Science is already a compulsory subject. The robot is an add on to the curriculum as an integral part of learning process. The child naturally switches from textbook to robot.

In Switzerland, price remains a definite setback; not all schools can afford a classroom robot. Lack of training for teachers, inadequate equipment and poor technology are also holding back a general rollout. In many schools the WiFi signal is either too weak or the teachers do not have their own computers. “Then you bring in a humanoid, and you don’t even have a technician at school”, Mondada lamented.

The Digitalswitzerland initiative, which promotes Switzerland as a hub for digital innovation, recognizes that there is “undoubtedly still untapped potential, although schools have already made great strides in introducing educational robots”.

The challenge we are facing today is that the digital divide is widening, as not all families are equipped with the right or sufficient technology,” wrote Digitalswitzerland when contacted. The organization is a nationwide, cross-sector initiative that aims to boost Switzerland’s role as a digital innovation hub.

In the IMD ranking for digital competitiveness, which ranks the capacity of an economy to adopt and explore digital technologies, Switzerland slipped from fifth to sixth place in 2020. In the area of knowledge, which also includes education and training, the country ranked third.

To promote the country’s digital competitiveness, Digitalswitzerland launched the Computational Thinking Initiative in 2018, of which the robot “Thymio” is part. The stated aim is to promote digitization skills in schools throughout Switzerland.

There is one area of application, though, where Switzerland is a front-runner. For years, small robots called “Nao” have sat in for sick children at school, enabling them to keep interacting with the class, whilst at home or in hospital. “This is a very successful project, which shows that educational robots can really have a huge added value,” Seufert pointed out.

It’s not all about play

One of the biggest challenges, in Mondada’s view, is making sure that the children do not just play around with the robot but also learn. He argues the teachers first have to grasp the basic technologies behind these new tools to use them efficiently. “The challenge is to have the teachers understand the potential and how they can use this tool in an interesting way.”

As Mondada notes, there is still a large gap between science and how it is applied in schools. With his EPFL learning centre, he intends to develop training of teachers to better help them understand the robots. Mondada developed the mini-robot “Thymio” for this very purpose. This educational robot is easy to program by users and provides an easy introduction to robotics

Danger

It’s not all upside. Risks for users exist. Experts see the danger that children, in particular, may develop an overly strong emotional bond with a humanoid robot. Mondada quotes an example from the US military. In simulation exercises, soldiers saved robots at the expense of their own or other people’s lives. In Japan, where robots are integrated in everyday life, people are already marrying them.

Despite this, Seufert advocates promoting knowledge of how robots function and the skills needed to use them properly. She argues that using robots in a beneficial way is better than ignoring their potential.

More

The ethics of artificial intelligence

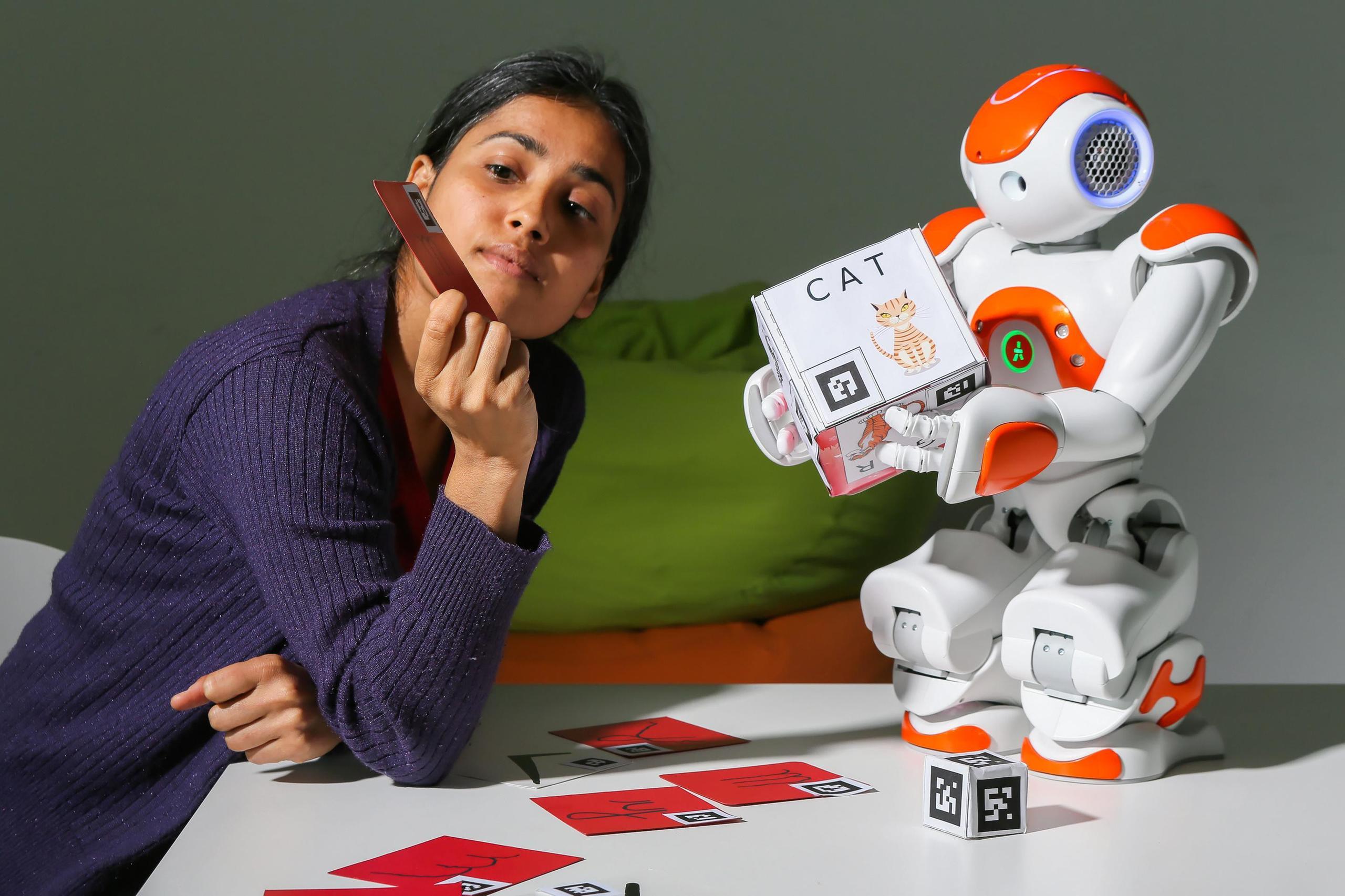

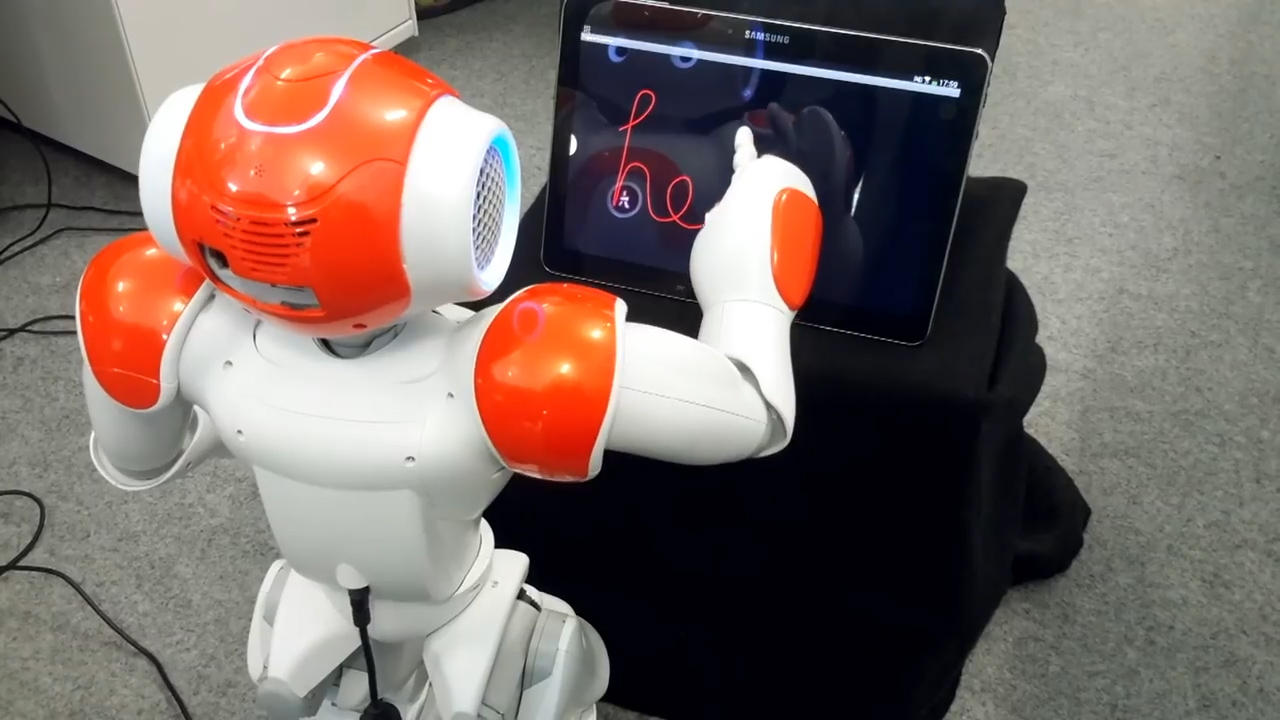

Both experts agree that the mega-trend in educational robots is clearly heading towards artificial intelligence (AI). Robots give AI a face. Another EPFL project is pursuing an interesting approach; here, schoolchildren are not simply using a robot as a learning aid, but teaching it content themselves.

So where is this journey taking us? It is unthinkable that robots will one day replace teachers, at least in European countries, says Seufert: “Creativity and enthusiasm – that’s our job as teachers, and a machine will never be able to replace that.”

Translated from German by Julia Bassam, SWI swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!