Switzerland mulls raising the retirement age for women

The Swiss government wants to raise the retirement age for women by one year to bring it in line with that of men – 65 years old. Most industrialised countries have already enacted such reforms, but the issue is politically charged.

New retirees in Norway and Iceland are the oldest of all developed countries; in these Nordic states, you have to work until the age of 67 to qualify for a full pension. The laws, introduced in the second half of the 2000s, also don’t include any difference between men and women.

Women in Switzerland, meanwhile, can retire at the age of 64, while men must wait until 65. The government has long wanted to eliminate this gender gap and level the retirement age upwards, which would bring the country into line with recommendations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

More

How to guarantee the pensions of the next generation

On Monday, March 15, the Swiss Senate approved the government’s AVS (old age and survivor’s insurance) reform project, which wants to move in this direction. While senators didn’t contest the need for the reform, they did debate the details.

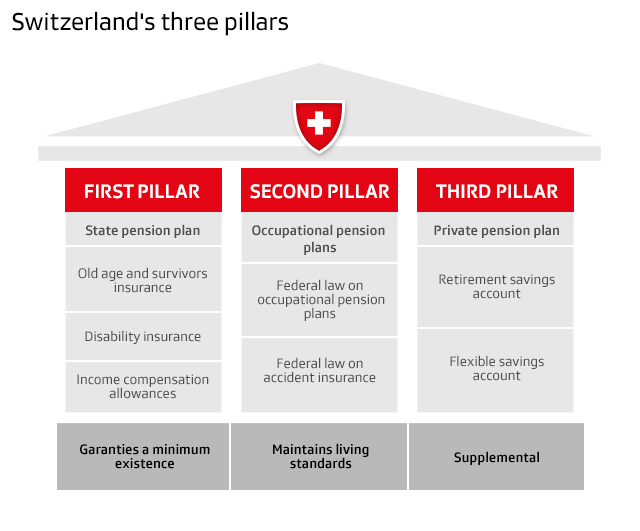

The old age and survivor’s insurance (AVS) is the first of three ‘pillars’ which make up the Swiss pension system, designed to guarantee a minimum subsistence level to all retirees who live or have worked in Switzerland.

Financed by a pay-as-you-go model, the finances of the AVS have been worsening for several years, a trend which is expected to be exacerbated over the coming years as the ‘baby boomer’ generation retires. The Federal Social Insurance Office (FSIO) predicts the accumulated deficits of the AVS will exceed CHF23 billion in ten years – if no action is taken.

To tackle this situation, the reform project dubbed “AVS 21” foresees an increase in value added tax and a raising of the retirement age for women to 65, along with certain other compensatory measures. The government hopes the measure will allow it to save CHF10 billion between 2023 and 2031.

Towards an average retirement age of 66

The retirement age for Swiss women is on a par with OECD countries, which in 2018 was 63.5 for women and a little over 64 for men, according to the organisation’s “Pensions at a Glance 2019” report.

But in recent years, aging populations and expected financial deficits have led most governments to increase the retirement age, often leading to heated disputes.

The financial pressure emerged earlier and more forcefully in systems entirely financed by pay-as-you-go models, where contributions by the current workforce pay for the pensions of current retirees. Such systems are naturally more exposed to demographic evolutions than in mixed systems such as Switzerland’s – where only the first pillar relies on pay-as-you-go financing. The other two pillars are financed by individual contributions.

Depending on national specificities, reforms to the pension system in future are set to be more or less gradual or drastic. The OECD reckons that the retirement age in Denmark or Holland, for example, will be extended beyond the age of 70 for both sexes. Across its 37 industrialised member countries, from now until 2060, the average OECD retirement age will gradually increase to 65.7 for women and 66.1 for men. If it adopts the ‘AVS 21’ reform, Switzerland will remain slightly behind these trends.

Age gaps to disappear

The Pensions at a Glance report also indicates that the gap between women and men will gradually be eliminated in most countries where it still exists. Today, the retirement age is lower for women in 19 OECD and G20 countries. In Austria, for example, women can still retire five years earlier than men.

In future, there will only be a gap in five OECD countries, including Switzerland. Elsewhere, a five-year gap will remain in Argentina, Russia, China, and Brazil, and will be reduced to two years in Romania.

The age gap, a ‘patriarchal’ system

Jérôme Cosandey, French-speaking director and head of political and social research at the Avenir Suisse think tank, says this international comparison shows that not only is the Swiss reform “not very ambitious”, but that a harmonisation of retirement ages is needed.

“The four other OECD countries which have not yet done it – Poland, Hungary, Israel, and Turkey – are not exactly organisational models of equality between men and women,” he tells SWI swissinfo.ch.

More

Pensions – what women need to know

The political debate in Switzerland has focused on the question of the fairness of a reform aimed at only half of the population. But according to pensions specialist Cosandey, the introduction of the age difference was in itself the result of a “very patriarchal” system.

When the AVS was introduced in 1948, the retirement age was the same for both men and women – 65. It was only during the reforms of 1957 and 1962 – before the introduction of nationwide women’s suffrage in 1971 – that politicians decided to lower the retirement age for women to 63, and then to 62, Cosandey says.

The government’s argument at the time was based on the “physiological disadvantage of women despite their higher life expectancy”.

It was only during the last revision of the AVS in 1997 that it was decided to gradually raise the retirement age of Swiss women from 62 to 64, in return for other advantages given to them, explains the research manager.

Women earn less in retirement

Opposition to the latest reform comes mainly from feminists, trade unions, and the left wing of the political spectrum. The Social Democrat Party believes it is a reform that will happen “on the backs of women”.

“We are being sold this project as a step towards equality, but it is in our working lives that we must first achieve equality. We are still far from that,” says Michela Bovolenta, a feminist activist who is also central secretary of the Swiss Union of Public Service Personnel. For this staunch opponent of increasing the retirement age, “a measure like this would further deepen the inequalities between men and women”.

Lower wages, high prevalence of female part-time work, fragmented professional paths, glass ceilings, more difficult work sectors, unequal division of household tasks: “there are still so many accumulated inequalities in active life which translate into pensions that are significantly lower for women than for men,” Bovolenta says.

These life-long inequalities impact the capacity of women to contribute to the occupational (second pillar) and private (third pillar) pensions. Women today are largely over-represented amongst the elderly poor. In the OECD, their pensions are on average 25% less than those of men, a figure rising to almost a third in Switzerland – a gap which is “likely to remain high” in the future, but which “improving the situation of women in the workplace will help to close”, notes the organisation.

Third time lucky?

While it claims to be “alert to the issue of wage inequalities”, the Swiss government also believes that they “must be fought upstream, where they appear”, independently of the question of the retirement age for women.

The government is treading on dangerous ground – it has already failed twice to implement its pension reform plans. The first effort was defeated in Parliament in 2011, while the second was rejected in a referendum in 2017. Polls showed that women had strongly come out to defeat the text.

As for the latest reform project, the parliamentary debates which began on Monday will define the compensation measures and transition timeline. “An exercise in realpolitik” is brewing, says Cosandey.

“They [government and politicians] will have to persuade those who are directly affected, because with the system of direct democracy, it is the people that will have the last word.”

More

Government hopes for ‘first successful pension reforms’ of the century

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.