The most critical questions about the Swiss central bank’s huge losses

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) booked a CHF132 billion ($143 billion) loss in 2022 and suspended profit-sharing transfers to the Confederation and cantons. What does that mean exactly? And how does the SNB fare in international comparison?

Last year, the SNB lost more money than ever before. And it is not alone: central banks around the world also recorded heavy losses. As a consequence, money from central banks in many countries ceased to flow to governments.

Have other central banks suspended profit sharing?

Yes. Besides the SNB, the central banks of Germany and The Netherlands will not pay out profits this year, along with most regional branches of the United States Federal Reserve. Britain even expects £230 billion (CHF260 billion) to flow in the opposite direction, from the Treasury to the Bank of England, over the next ten years. The latest agreement between the Swedish government and the central bank stipulates the same measure should the Riksbank’s equity fall below 20 billion Krona (CHF1.8 billion).

+ Should the SNB give more to the government and cantons?

How bad is the SNB loss in historical comparison?

For a long time, the Swiss central bank’s profits and losses were in the single-digit billion range. For example, the SNB posted an CHF8 billion profit in 2007, followed by a CHF4.7 billion loss the next year. More recently, these figures have fluctuated by a much higher margin. The record CHF54 billion profit in 2017 stands in stark contrast to the CHF132 billion loss last year. The average SNB annual result since 2005 has been a CHF3.5 billion profit.

What is behind this stronger fluctuation?

This is explained by the SNB’s ballooning balance sheet, which has grown from CHF130 billion in 2007 to over one trillion francs now. Every 1% change in profit or loss is now expressed in much larger figures than in the past.

Why has the SNB’s balance sheet increased by so much?

The SNB wanted to combat the excessive appreciation of the Swiss franc between 2005 and 2021. This was achieved by the central bank buying large quantities of foreign currencies.

Why was the loss so high last year?

The primary reason was that the price of company shares and bonds collapsed in 2022. Secondly, the SNB’s huge stockpile of foreign currency investments lost value as the euro depreciated against the Swiss franc.

+ Why the Swiss central bank can’t go bankrupt

What are the rules that govern SNB profit sharing?

The SNB accumulates a so-called Distribution Reserve from its profits and has total discretion as to how much money flows into this reserve. The money paid out to the federal government and cantons comes out of the Distribution Reserve.

However, losses are also charged to this reserve that can also turn negative. In this case, the law states that no profits may be shared.

Another term used to describe this situation is a “balance sheet loss”. Last year, this amounted to a minus of CHF39 billion. Under these conditions, payments to the Confederation and cantons are suspended.

Was the SNB profit distribution in 2010 illegal?

In 2010, the SNB gave CHF2.5 billion to the Confederation and cantons despite reporting a balance sheet loss. This contravened the rule that profits cannot be shared if there is a net loss. So was this payout illegal?

The following year, 2011, the profit-sharing agreement was revised and the SNB launched a legal review of its distribution practice, after which it obviously changed its interpretation of the rule.

The current SNB president, Thomas Jordan, was vice-president in 2010 and was responsible for the distribution back then.

What is the profit-sharing agreement?

The finance ministry and the SNB negotiate at regular intervals how much money the central bank pays out each year.

The current agreement states that CHF6 billion will be paid out if the Distribution Reserve reaches CHF40 billion. Cantons receive two-thirds of the handout while the Confederation gets the remaining third.

If the reserve is negative, then nothing gets paid out and there is a spectrum of payments that are made in between the two extremes.

How much money has been paid out since 2005?

Since 2005, the SNB has made a cumulative profit of CHF63 billion and distributed around CHF42 billion.

Where does the remainder of the SNB profits end up?

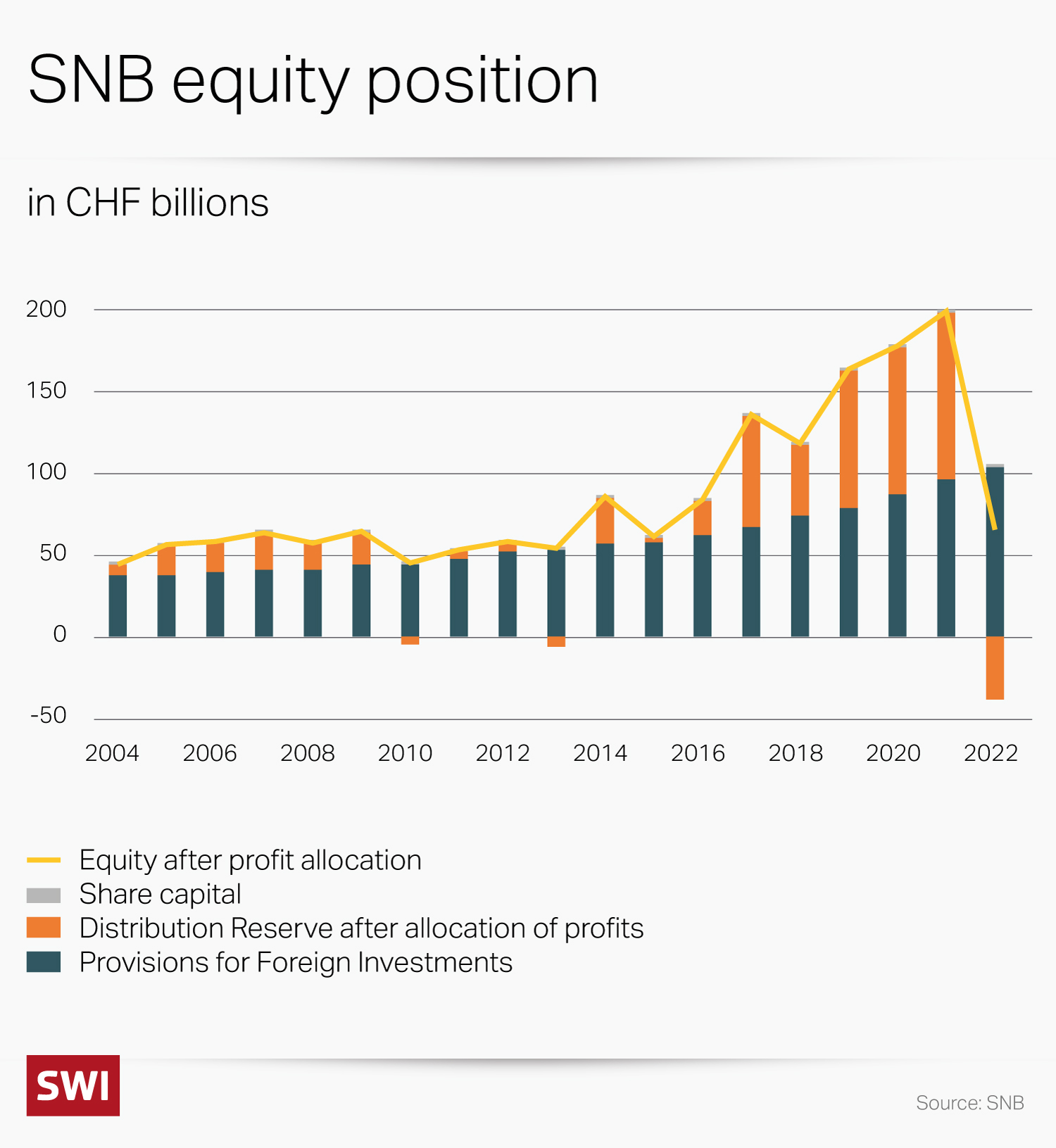

A considerable chunk of SNB profits ends up in the so-called Provisions for Foreign Investments, which currently stands at some CHF105 billion.

The SNB uses this reserve to calculate its equity, which is why losses are not charged to this account.

The size and function of the Provisions for Currency Reserve have attracted criticism in parliament and from some economists.

What’s the outlook for future profit-sharing?

Future payments can only be made again once the Distribution Reserve tops CHF2 billion, which means the SNB would have to make a CHF52 billion profit this year.

The SNB stipulates that the first CHF11 billion of profits must be channeled into the Provisions for Foreign Investments before anything can be paid into the Distribution Reserve.

What is SNB equity?

This the central bank’s net assets, which equates to the value of all investments minus its debts. The SNB’s equity currently stands at CHF66 billion. This consists of CHF25 million share capital, the Provisions for Foreign Investments of CHF105 billion and Distribution Reserves, which stand at -CHF39 billion.

What is the SNB equity ratio?

This is derived by calculating the value of SNB equity against the investments the central bank makes. The equity ratio is currently around 7%.

This means that if the SNB makes a further loss of 7% on its investments, its equity capital would turn negative. In other words, the value of SNB debts would be higher than its assets.

How does this compare globally?

The Swedish central bank recently published a global comparison of equity ratios in different countries.

This shows that the equity ratio of central banks in Australia (-2%), New Zealand (3%) and the US (1%) is lower than Switzerland’s. Sweden (10%) and The Netherlands (8%) have marginally better central bank equity ratios.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.