The Romans of Basel open their doors to the public

A newly refurbished replica of a Roman house is shedding fresh light on the excavated ruins of Augusta Raurica near Basel. Visitors to the site are literally being asked to place themselves in the shoes of the Romans.

Catherine Aitken, who is responsible for the educational aspects of Augusta Raurica, describes the former town while walking across an empty field not far from the Rhine River to the east of Basel. “What you have to imagine here is an open space where the market stalls would have been, and on either side colonnades with small shops behind them.

“At one end of the forum would have been the temple and at the other end the town hall and administrative buildings. Part of the town hall is still visible.”

Augusta Raurica was a bustling colonial town which the Romans built on the river about 2,000 years ago. It reached its zenith and counted about 20,000 inhabitants in the third century before being flattened by an earthquake.

Not much was heard of the town for more than 1,000 years until excavations revealed what eventually proved to be the most impressive antique Roman theatre north of the Alps.

The extensive ruins are now surrounded by urban and industrial sprawl, and the drone of the nearby motorway and railway tracks are ever-present reminders that the stones and statues lie in modern-day Switzerland.

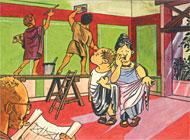

The renovation of the Roman house replica, however, is an attempt to bring visitors closer to everyday life as it was in the Roman town.

“The Roman house was built in the 1950s, and we really wanted to breathe a bit of fresh life and colour into it, to make it more authentic than it used to be,” Aitken says.

“A number of the rooms have been completely repainted, using some bold colour schemes, which are rarely found today – sort of apricot orange beside pastel blue.”

On entering the house’s private bath, children are encouraged to try on Roman clothes. The sound of dripping water can be heard in the background, and painted fish and stylised dolphins swim across the domed ceiling.

In the kitchen, a wax figure of a boy sits on a wooden bench, which, upon closer inspection, is a toilet. The boy relieves himself in full view of everyone in the room.

“Of course it’s somewhat unhygienic (placed in the kitchen), but it had its practical reasons for being here, because it was one way of getting rid of your waste water. You could use it to flush your toilet,” Aitken explains.

Romans didn’t value privacy as much as modern western societies, and visitors wanting to get a sense of how it once was can take a seat beside the boy.

Aitken has also prepared games and created role-plays (with English versions) to stimulate an interest among schoolchildren in the Roman period. One of the stories involves the mistress of the house discussing the menu plan with her cook ahead of a banquet.

The various scenarios are based on finds at Augusta Raurica, the significance of which would otherwise be difficult to grasp.

“The mistress of the house really wants to have lentils with oysters. Oysters were imported from the North Sea. We’ve found a number of shells so we know they were eaten here.”

The slave is sent off to buy the oysters but comes back and says ‘no, there aren’t any today’, so the cook and the mistress of the house have to sit down and think, ‘oh, what shall we do instead?’ and then it’s left up to the children to come up with an idea.”

Before entering the bedroom, visitors are advised to read a passage of a translated Latin text describing a day in the life of a boy in a well-to-do Roman household, like the one at Augusta Raurica:

“I wake up at the break of day and call my servant. I get him to open the window. He does it immediately…I ask for my socks and shoes because it is cold…I am brought a clean towel and water in a bowl. I pour it first over my hands and then face. I rub my teeth and gums. I spit and blow my nose…”

Nearby, a dark tunnel leads down into a recently excavated well house. It provides clues that Augusta Raurica also had its share of excitement to break up the routine of daily life.

Archaeologists were surprised not only to discover the well house but to find human bones among the rubble inside. They suspect that, since the Romans weren’t in the habit of throwing their dead down wells, the bones could be the only remaining evidence of a hideous crime.

by Dale Bechtel

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.