The Second Cold War – as cold as outer space

The Russian war against Ukraine has pretty much frozen collaboration on space exploration between Moscow and the West, including Switzerland. However, the new space race could represent a huge opportunity for the manufacturers of the “free world”.

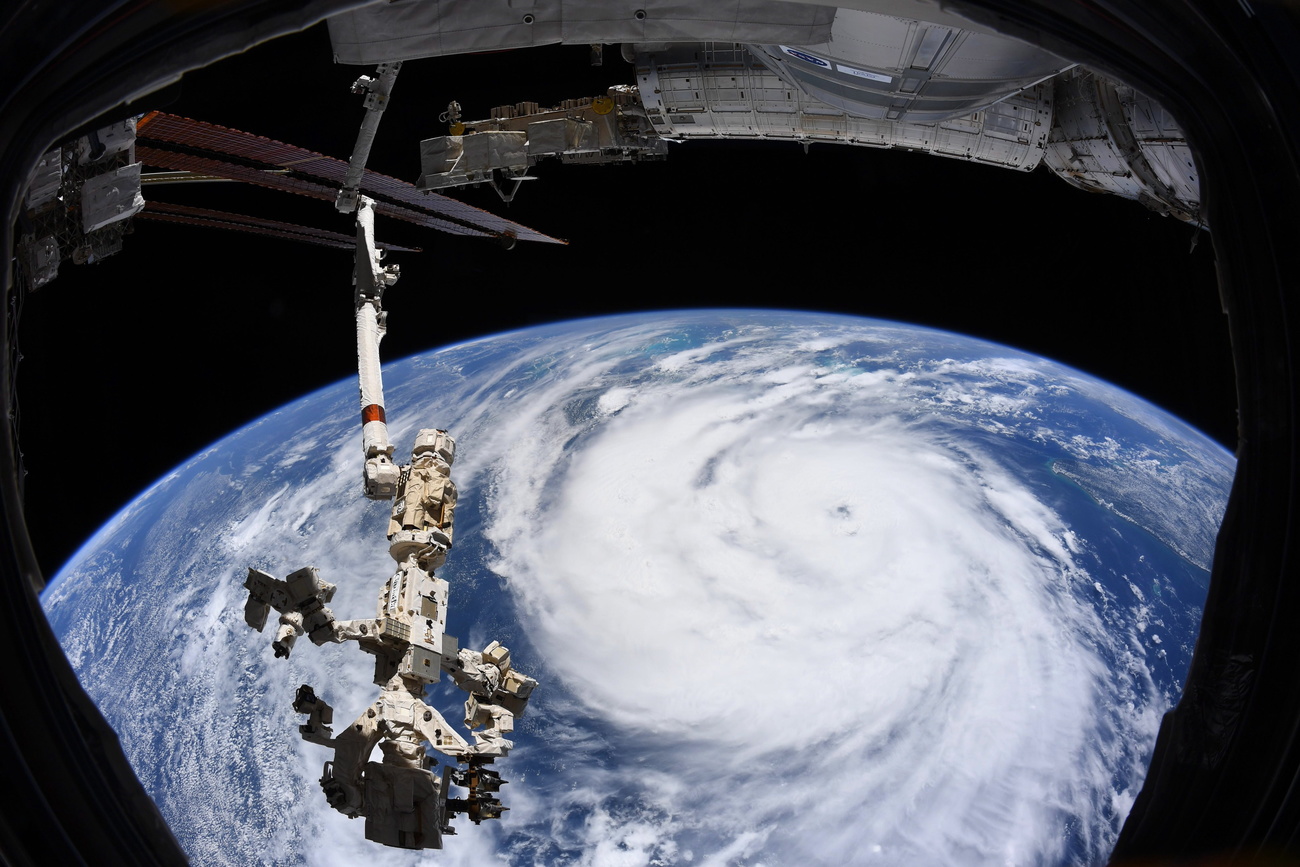

Russia is one of the major players in space exploration, but since its tanks rolled into Ukraine in February and Western sanctions were imposed, Moscow has withdrawn – or been suspended – from all collaboration projects in space with the West. Only the International Space Station (ISS) is keeping the spirit of détente alive, with its three Russian cosmonauts, three Americans and one Italian. For everything else, however, it’s another Cold War.

The first project to be affected was the European mission ExoMars, which has lost its Proton rocket and lander necessary to reach its destination. After the orbiter launched in 2016, this time the aim is to land a rover on the surface of the planet. The rover will be equipped with a high-tech camera of Swiss design and manufacture, which will search for traces of life.

Take-off was first planned for 2018 and then postponed to 2020, but delays in shipments and the Covid-19 pandemic meant the launch was pushed back further to 2022. Now it isn’t expected until 2024 or even 2026, as launch windows for Mars are favourable only every two years.

February 26: Russian state television announces that following threats of sanctions, Soyuz rockets will no longer take off from the European Space Centre in Kourou (French Guiana), where they account for a third of launches. “We are continuing to develop Ariane 6 and VegaC in order to guarantee Europe’s strategic autonomy in terms of launchers,” said Thierry Breton, the commissioner responsible for EU space policy, in a statement.

March 17: “Deeply deploring the loss of life and the tragic consequences of the aggression against Ukraine”, the ESA Council “fully aligns itself with the sanctions imposed on Russia by its Member States” and abandons the launch of its ExoMars probe in September on a Russian Proton rocket. In effect, the mission is delayed by at least two years.

April 3: Dmitry Rogozin, the then head of the Roscosmos agency, announces via Twitter that he will make recommendations “in the near future” on Russia’s continued participation in the ISS. He was later replaced by former deputy prime minister Yury Borisov.

April 13: ESA announces that it is suspending cooperation with Russia on the Luna-25, Luna-26 and Luna-27 missions, citing “Russian aggression towards Ukraine and the resulting sanctions”.

April 30: Interviewed by Russian state television, Dmitry Rogozin evades the question of when Russia will withdraw from the ISS. “The decision has been taken, we are not obliged to talk about it publicly,” he said. He added that Roscosmos “will inform its partners of the end of their work on the ISS with one year’s notice”. No further details were given.

Wanted: new rocket

“The European Space Agency (ESA) defends the interests of its shareholder states such as Switzerland. It is wrapping up a much-expected industrial survey which aims to show the options for going ahead with the ExoMars mission,” said Renato Krpoun, head of the Swiss Space Office at the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) in an email. Concretely, ESA is looking for a new launching rocket and a new landing capsule.

Leaving aside the mission’s delay, Josef Aschbacher, ESA general director, is not particularly worried. “We will establish a good partnership for ExoMars,” he said on June 15 at an online press conference with NASA administrator Bill Nelson. His American partner had come to the Netherlands to join the ESA Council.

>> The European Space Agency (ESA) presents its ExoMars rover in this YouTube video.

This does not mean the two agencies intend to merge ExoMars and Mars Sample Return. NASA’s programme aims to bring back to Earth samples collected by the American rover Perseverance. This, like the rover of ExoMars and all previous rovers, is mounted with electrical engines made by Swiss manufacturer Maxon, whose parts are fixed to the wheels and direct the robotic arms which move the samples into storage.

Three missions to the moon

Switzerland, together with ESA, also had a significant stake in the Russian programme Luna, named after its prestigious Soviet forerunner of the 1960s.

The European and Swiss space instruments won’t land on the moon with Russian shuttles. Still, Renato Krpoun points out, “Switzerland, through its ESA membership, is also a partner in NASA’s Artemis mission to the moon”. The Alpine nation works with its partners to ensure Swiss and European space instruments are taken on different missions.

At this stage, three main players are planning to land on the moon: the West (Artemis), the Russians (Luna) and the Chinese (Chang’e).

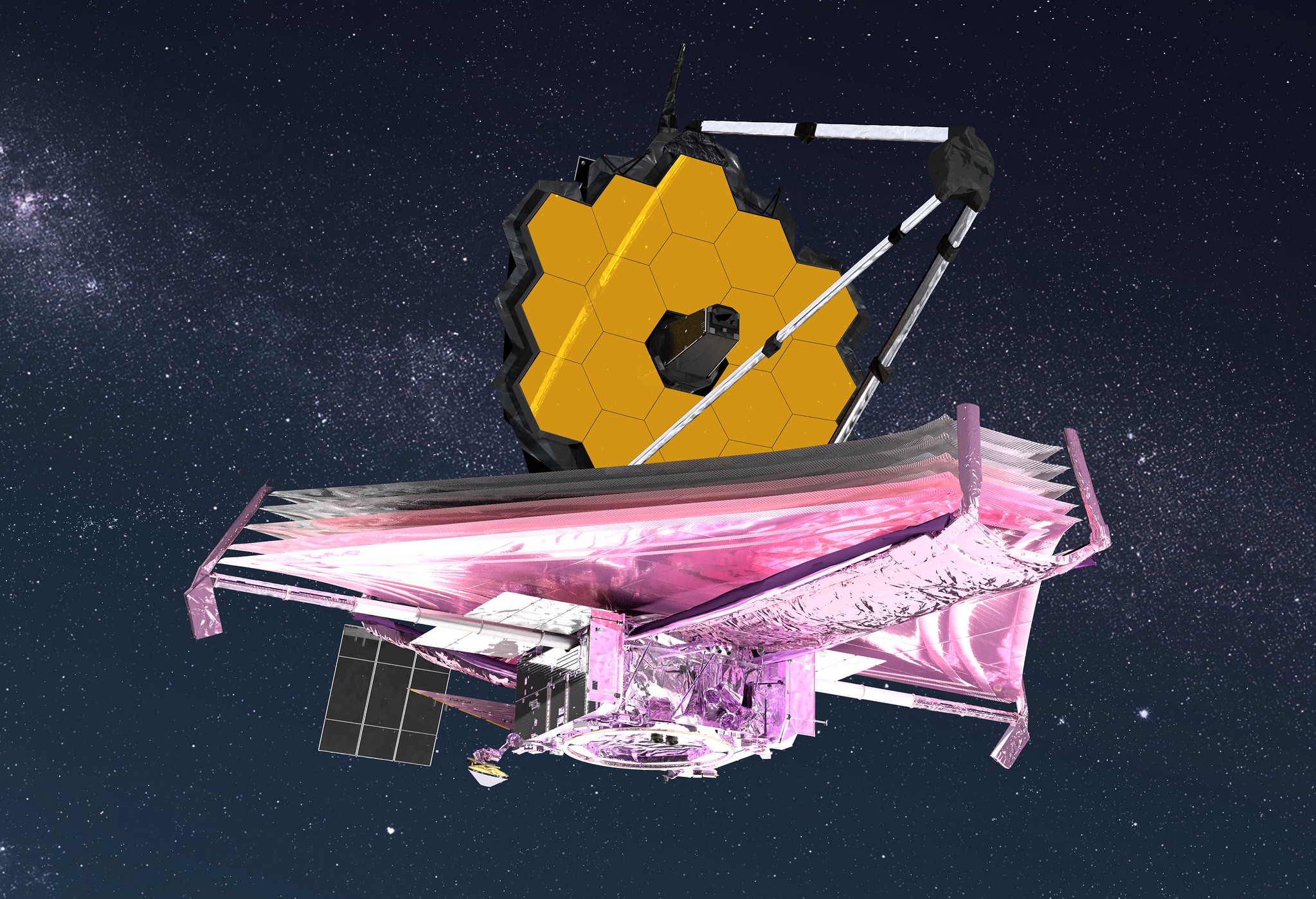

Claude Nicollier, the former – and only – Swiss astronaut, insists that the Western consortium is strong. “There has always been a solid partnership between Americans, Europeans, Canadians and Japanese. The James Webb space telescope illustrates this perfectly,” he said. “With Russia opting out, this association could even develop further.”

Western rockets

The Artemis moon programme represents a further example of Western countries coming together. In 2024 and 2025, the SLS launch vehicle, the biggest rocket ever built, will send the spacecraft Orion to the moon, together with its landing capsule (manufactured in the private sector) and its support module, a huge cylinder located under the spacecraft (the same construction as for the Apollo shuttles). The support module will provide Orion with electricity, propulsion, oxygen, water and heating.

>> “Why the moon?”, a NASA promotional video for its Artemis moon programme.

This module will be “made in Europe” – a first for an American-manned mission. The names of NASA and ESA will both be displayed on the huge rocket. One of the most important Swiss elements will be inside the module. The firm Beyond Gravity (formerly RUAG Space) has planned the solar panels’ orientation mechanism. These panels measure four metres by seven metres and will provide electricity for the module’s 33 engines.

The West has even more plans for both the moon and Mars. Next year the European Ariane 6 will be tested for medium- and long-range journeys. The European light rocket Vega-C successfully completed its first flight on July 13.

There is therefore an alternative to the Soyouz, the Russian spacecrafts that will no longer take off from Kourou in French Guiana. Their first launch from the European launchpad was in 2011. Twenty-six launches followed, compared with 52 Ariane and 20 Vega. The last lift-off of Soyouz, 14 days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, put 34 OneWeb constellation satellites into orbit. The British high-speed internet provider has since switched to SpaceX.

‘Tragic events’

What about the flagship International Space Station, a symbol of space cooperation? The ISS was set up more than 20 years after the historical handshake between American astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts in 1975, in the midst of the Cold War. All were part of the joint Apollo-Soyouz mission (the Soviets called it the Soyouz-Apollo mission).

Should the threat from Dmitry Rogozin, until recently director general of state space corporation Roscosmos, to withdraw cosmonauts and logistical support for the station be taken seriously? “For the moment the ISS is operating normally,” Krpoun says. “All signatory parties to the 1998 international agreement, including Switzerland, are doing their share to ensure that everything functions well. This is in the interest of all parties.”

However, things are not that simple: the current state of the space station would be a valid reason to withdraw. The ISS was originally set to last until 2012, but this date has been postponed repeatedly. Its maintenance and successful orbiting is primarily the responsibility of Russia. Since the Americans retired their space shuttle in 2011, the Russians have been the only ones able to dock on the ISS, thanks to their Soyouz. This exclusivity ended when shuttles from private actors, such as SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, were launched. As for the ability to maintain the station on the right orbit, NASA is now developing its own capabilities by utilising the automatic Cygnus spacecraft (from Northrop Grumman) to replace the Soyouz.

Bill Nelson stresses that the ISS team “is very professional. The exchanges between the two control centres at Houston and Moscow are also very professional.” He adds that the international partnership is strong concerning the space programme, “whatever tragic events Putin has unleashed in Ukraine”.

Claude Nicollier doesn’t take Rogozin’s threats too seriously either, seeing them as a “sort of blackmail”. Nicollier says he would of course greatly regret a Russian withdrawal from the international Space programme, but the invasion of Ukraine is “so wrong, irrational and tragic, with all the consequences we know for Ukraine, but also for Russia and the world” that an end to the space partnership with the Russians “would not be the war’s worst consequence by a long shot”.

Russia is already focusing on building its own space station, the first module of which should be sent into space in 2025. The Chinese got their own station one year ago; they have just sent in a new crew.

New challenges

The split with Moscow is not only about a space station and some rockets. “Nearly every project is affected, because of the sheer number of components and raw material Russia used to supply,” Josef Aschbacher said. “To give an example, the titanium reserve tanks which are built into many spacecrafts.” Therefore, ESA has already signed contracts with new manufacturers in Europe and in the US.

Raphael Röttgen, manager of E2MC Ventures, a consultancy specialised in space investments, believes it will be an opportunity for those who can supply components no longer delivered by the Russians, especially public sector partners such as ESA and rocket manufacturing companies Vega and Ariane.

“Even though what is happening is extremely sad, it has boosted military expenditures, also in Europe,” he said. “Of course, space is of strategic importance for the military, therefore part of the money is going to flow to the aerospace industry.”

One crew

Röttgen isn’t alarmed by Rogozin’s threats either. “As always in times of war, messages are sent. But one needs to look at who they are meant for. In the case of Rogozin’s comments, they were in Russian, and are circulating mainly on Russian social media. To my understanding they were aimed at a Russian audience and don’t represent a serious threat.”

Is the spirit of the Apollo-Soyouz encounter long gone? For Nicollier the answer is simple. “Inside the ISS we work together. This has always been the case, whatever the political issues on Earth,” he said, before admitting that the current problem is going to be a bit more difficult than when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, when nothing much happened.

Nevertheless, based on the photographs and the official press releases, the message is clear: the ISS team stands as one. It is “one crew”.

Translated from French by Johannes Waardenburg/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.