The fragile growth of Swiss forests

Although Swiss forests have been growing in recent years, they are at increasing risk of drought, wildfires and attacks by invasive species.

The total surface area of woodland in Switzerland has doubled since 1850, and an additional 4,000 hectares (11,000 acres) of forest has sprouted every year over the past three decades.

The increase is mainly due to the loss of Alpine grasslands formerly used as pastures.

“To some extent these grasslands became less economically important,” says Jacqueline Bütikofer of the Association of Swiss Forest OwnersExternal link. “It doesn’t take long for scrub and trees to take over the area left untended,” she explains.

The country’s woodland enjoys strict legal protection, which aims to ensure the preservation of forests both in terms of surface and geographical extent, as well as a natural habitat.

These constraints make deforestation almost impossible, even in lower-lying areas where the pressure from civilisation is high.

“Clearances are very rare and only if no other solution is at hand,” says Bütikofer.

More

Forests in focus

Olivier Schneider of the Federal Office for the EnvironmentExternal link adds that 90% of the 160 hectares of woodland that disappear every year are re-forested.

Fire and water

Despite the high legal protection, Swiss forests are still threatened – notably by drought. “Some forests clearly suffer from lack of water,” Bütikofer says. “In canton Jura, for instance, the soil contains a lot of limestone, which makes the water drain off quickly.”

The situation is particularly difficult for beech trees, and in September authorities declared a forest emergency when 200,000 cubic meters of trees died.

The Federal Office for the Environment agrees that the lack of water has hit a vast part of the country – from Zurich in north-eastern Switzerland to the north-western region of Jura.

“Three things combined to make an impact. First it was Storm Eleanor in 2018, followed by a dry spell and an increase in invasive insects,” says Schneider. “But the overall situation is not alarming.”

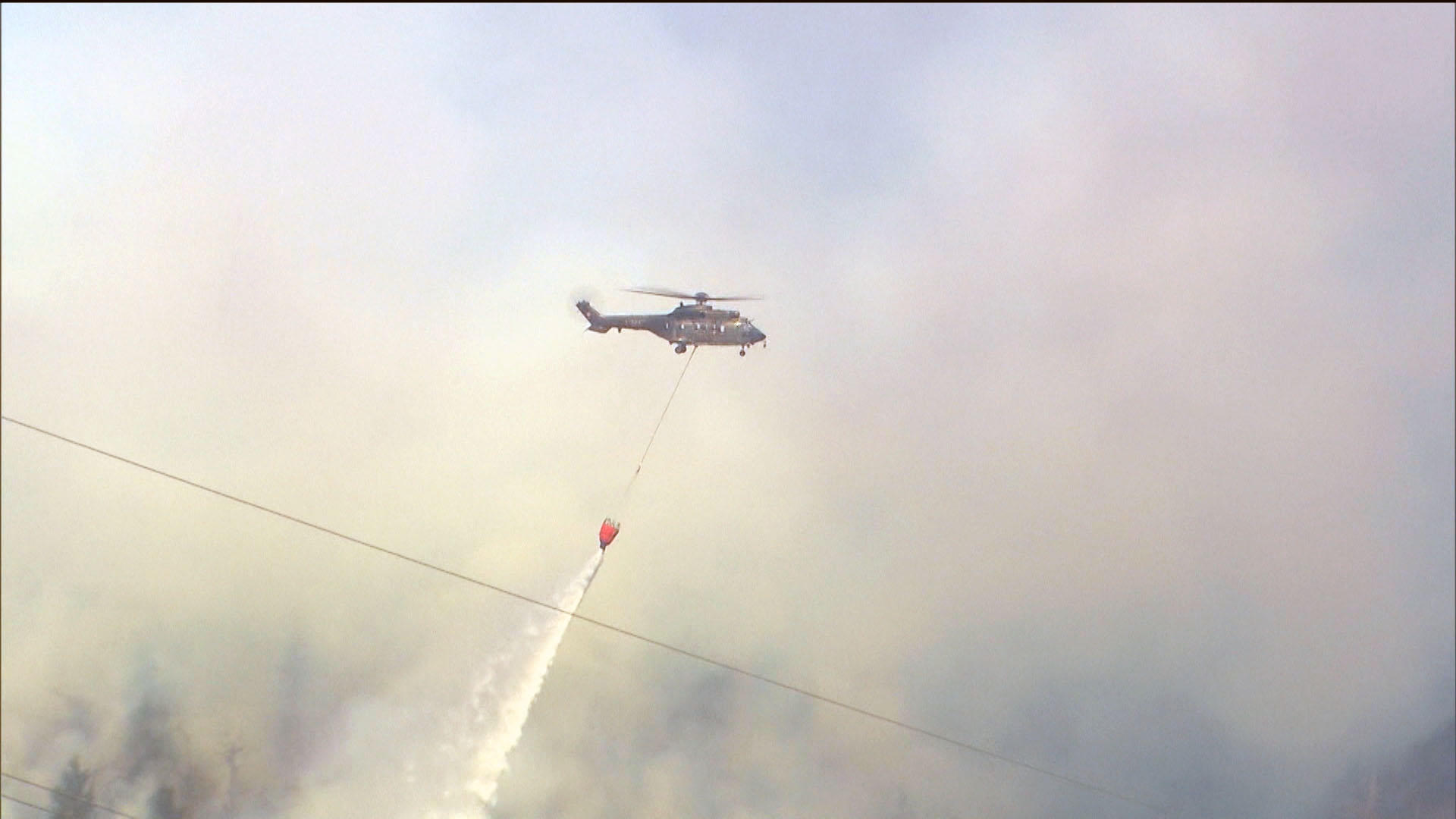

Another factor are wildfires such as those that have been raging in southern Europe, North America and the Amazon. Such fires also pose a danger in Switzerland.

These fires used to be limited in size and confined to areas north of the Alps, according to Schneider.

More

Graubünden gears up for more forest fires

“But the situation has changed. Most cantons consider taking prevention measures, limiting the amount of dead wood in highly sensitive zones near built-up areas. The authorities have published maps for this purpose,” Schneider says.

For the time being, the situation is under control thanks to the prevention and surveillance measures, as well as the relatively small surface of woodland.

“The risk is increasing, but the fires are no major threat yet,” notes Bütikofer.

Beetles and fungi

In addition, there is also the threat of harmful insects and other organisms damaging the forests. Bark beetles and budworms are the best-known domestic species. Other exotic insects include tree borers and the Asian long-horned beetle.

While the fight against some harmful insects is possible – the latest example is the eradication of the Asian long-horned beetle in canton Fribourg – it is much harder to win the battle against fungi.

“The species that causes a wilting of the ash is spreading fast because of the spores and it is hard to contain it,” warns Schneider.

The biological threats are not a new phenomenon and the forests eventually recover from the diseases. Schneider refers to the chestnut blight in the 1950s and a disease that hit elm trees from the 1970s onwards.

“These trees were hard hit by the disease, but they never disappeared completely,” says Schneider. “Now they have begun to grow again.”

Despite all the threats, both Schneider and Bütikofer take an optimistic outlook. They believe that the measures taken will allow forests to survive in Switzerland.

“It was widely believed that the forests would die. The big lesson we learnt from the crisis in the 1980s is that trees die. But forests change and transform themselves,” says Bütifkofer.

“Trees that now grow in lower-lying regions existed in the mountains 100 years ago. In the near future we might even come across Mediterranean tree species,” Schneider says. Echoing Bütikofer, he adds: “Trees will die, but the forests will always be here.”

More

How to best protect Swiss forests

Adapted from French/urs

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.