Ukraine war is a windfall for Swiss arms industry

Production lines can barely keep up, stock prices are soaring, and requests keep pouring in from across Europe. The global rearmament effort in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is grist to the mill for Swiss arms companies.

Just days after Russian troops invaded Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced plans to allocate a special budget of €100 billion ($106 billion, CHF104 billion) to modernise his country’s army. On the heels of this decision, the Scandinavian and Eastern European countries declared that they, too, intended to drastically increase their military spending in response to the Russian threat.

Those decisions meant that workers at the Swiss factories in Altdorf and Zurich, which produce air defence systems, radar and ammunition for the German automotive and arms manufacturer Rheinmetall, are under pressure to speed up production. In a message to the staff, revealed by the weekly Handelszeitung, the director of Rheinmetall’s Swiss subsidiary, Oliver Dürr, railed against the “too long delivery times”, even as market conditions are at an all-time high.

Investors clearly appreciate Rheinmetall’s efforts to step up the pace: the company’s share value has more than doubled since Vladimir Putin attacked Ukraine. The German arms company anticipates a 15–20% increase in turnover.

Demand from NATO countries

Other large companies active in the sector in Switzerland are also benefiting from the generalised drive to rearm. The Swedish company Saab, which employs around 80 people at its site in Thun, canton Bern, has registered, “like most of the defence industry, increased interest in [its] products”, without giving further details. Here, too, investors are confident: the share price of the Swedish group, which focuses in particular on aeronautics and anti-aircraft defence systems, has risen steadily since February 24, when the war in Ukraine began.

The same goes for the Swiss-government-owned group Ruag, which has reported an “increase in requests [not necessarily orders] from NATO countries”. As Europe’s leading manufacturer of small-calibre ammunition, it says it is in close contact with its main customers, in order to plan its long-term production capacities.

At Rheinmetall, too, NATO members account for the lion’s share of new contracts. “Across the group, 87% of orders currently come from NATO countries, and the trend is upwards,” according to the German group’s spokesman, Oliver Hoffmann.

Similarly, the armoured-vehicle manufacturer Mowag, which is based in canton Thurgau and has belonged to the US company General Dynamics since 2004, is in touch with Germany and other European countries, according to the Tribune de Genève. “The weapons business is subject to long-term procurement cycles. So we have absolutely no way of knowing for now whether, or to what extent, these future needs will have a concrete impact on our order book,” the company’s spokesman, Pascal Kopp, qualified.

Rising exports

Last year, Switzerland exported CHF742.8 million’s worth of weapons and ammunition. This was 18% less than in 2020, a record year for the Swiss arms industry. In the long term, however, the trend is clear: over the last 20 years, sales of military equipment abroad have almost tripled. This surge looks set to continue, or even accelerate, if our survey of the main companies active in the sector in Switzerland is anything to go by.

Even the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), which grants export licences to arms manufacturers, sees good times ahead for the industry. “Demand for armaments is projected to grow worldwide. It is easy to imagine that this will also have an impact on arms orders from Switzerland,” said SECO spokesman Fabian Maienfisch.

By international standards, though, Switzerland is still an industry dwarf, with a share of global exports that is below 1%. The world market is dominated, not surprisingly, by the United States (40%), followed by France and Russia (13% each). Two other European countries, Italy (5%) and Germany (4%), make up the top five.

Technology transfer

Apart from Ruag and a few large international groups with specific activities on Swiss soil, the production of components for weapons and ammunition is spread across some 3,000 small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). These subcontractors are mainly active in the civilian sector and manufacture military equipment on a secondary basis.

Many machine-tool manufacturers, for instance, market machining solutions for metal parts, which are then used in watches, medical devices and high-precision weapons.

Overall, the arms sector represents just under 10,000 jobs in Switzerland, according to the BAK Economics research centre. This is a relatively modest figure compared to the 300,000 jobs in the Swiss mechanical, electrical and metal (MEM) industry. However, these military contracts are very important to Swiss SMEs, according to industry representatives, as they enable a technology transfer from the military to the civilian sector.

“International military-industrial groups operate at a very high technological level. This know-how can then be put to many other uses, which gives our companies a competitive edge,” explained Philippe Cordonier, director for French-speaking Switzerland of the MEM industry’s umbrella association, Swissmem.

‘Failure to render assistance to Ukraine’

Although it accounts for less than 1% of the country’s industrial exports, the arms industry regularly weighs in on political debate in Switzerland. It is a highly sensitive sector for a country that likes to spotlight its neutrality on the international scene.

The most recent controversy stemmed from Bern’s refusal to allow Germany to export Swiss-made ammunition to Ukraine. The federal government justified its decision on the grounds that Swiss law prohibits exports to countries that are involved in internal or international conflicts. This interpretation was not to the liking of some politicians, both right- and left-wing. The president of the centre-right Centre party, Gerhard Pfister, even accused the cabinet of “failing to render assistance to Ukraine”.

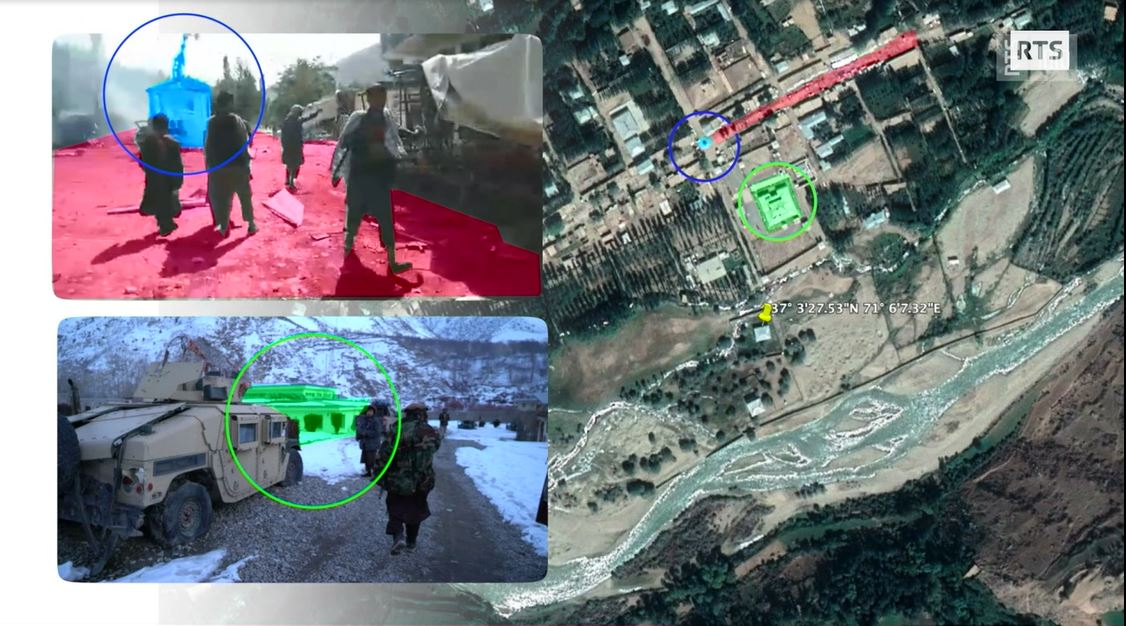

In recent years, scandals concerning the illegal presence of Swiss military equipment in war zones have proliferated. The latest example was the revelation by a consortium of journalists in February that a Pilatus PC-12 aircraft had been used in a deadly bombing in Afghanistan, and that Saudi Arabian forces were wielding Swiss-made assault rifles against Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Always scope for exceptions

Switzerland prides itself on having some of the strictest legislation on war material exports. This legal framework was further tightened on May 1. Swiss companies can now no longer export arms to countries that “seriously violate human rights”. This is the case, for example, of Saudi Arabia, which de facto has already been on the red list since 2015, because of its military intervention in Yemen.

Yet in 2021 Saudi Arabia was the sixth largest recipient of Swiss weapons, with orders worth over CHF50 million. This is in line with Article 23 of the War Material Act, which, according to SECO, allows “the delivery of replacement parts for air defence systems and the corresponding ammunition previously delivered by Switzerland”.

Meanwhile, no clear-cut decision has yet been made concerning Qatar, although human rights organisations accuse the Gulf State of being responsible for the deaths of 6,500 migrant workers on building sites for the coming football World Cup. “SECO does not keep a list of countries that systematically and seriously violate human rights. Assessments are made on a case-by-case basis,” the government body’s spokesman, Fabian Maienfisch, asserted.

The war in Ukraine, however, marks a watershed. The increase in arms purchases by Western countries may well induce Swiss companies to be more exacting towards certain problematic countries. “The need to do business at any cost will be less pronounced within the sector,” Social Democratic Party parliamentarian Pierre-Alain Fridez said in an interview with Le Temps.

‘Good offices and good business’

But this is not enough to reassure Swiss anti-militarists. “The question is not whether a new scandal will erupt but when. The experience of recent years has shown that, despite all the controls put in place, Swiss weapons still wind up in war zones”, said Green Party parliamentarian Fabien Fivaz.

With each new disclosure, Switzerland’s image suffers another blow. The trade-off is just not worth it, in Fivaz’s eyes. “By exporting weapons of a value of several hundred million francs, we are feeding the global war effort. Switzerland pursues a dual policy of good offices and good business. I understand that this looks bad abroad.”

The industry’s defenders take a much more pragmatic view. “We already have much more stringent regulations than most other European countries. Tightening this legislation further would only penalize our industry. If we don’t sell these weapons, others will do it for us,” concluded Swissmem’s Philippe Cordonier.

For many centuries, Switzerland exported only mercenaries and no weapons – it was only after the First World War that an exportable war materials industry emerged in Switzerland.

The Hague Agreement of 1907 prohibited neutral states from exporting state-produced weapons, but this did not apply to the private sector. In addition, it stipulated that no deliveries should be made unilaterally to a warring party. From this, Switzerland developed a neutrality position of balance: in the then newly founded League of Nations, it advocated rearmament for Germany and, at the same time, disarmament for the Allies. With the result that German arms manufacturers settled in Switzerland in order to circumvent the Allied arms control regulations. During the Second World War, Switzerland tried to sell more war material to the Germans in order to compensate for the imbalance compared to its arms exports to Allies.

During the Cold War, this balance doctrine came under pressure, and Switzerland supplied primarily to the western part of the divided world. Its customers included not only flawless democracies but also military dictatorships. Despite widespread criticism, the official, bourgeois Switzerland stood behind the arms industry: a reduction in arms production was seen as a weakening of defence readiness – very much in the spirit of the Cold War. There was no contradiction with neutrality, on the contrary: the rash disregard of a nation for arms deliveries was seen as non-neutral.

This rhetoric disappeared with the Cold War and gave way to liberal economic arguments that feared too much regulation. This with the support of the population: initiatives that wanted to ban the export of war material altogether in 1997 and 2009 always provided important corrective measures, but were never adopted.

This section was added in March 2023.

Translated from French by Julia Bassam

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.