UN body puts illegal adoptions in new, criminal light

Olivier de Frouville, a United Nations human rights expert, says a report into Sri Lankan children illegally adopted and brought to Switzerland shows a clear connection between trafficking and enforced disappearances.

In May, de Frouville’s office urged Switzerland to investigate illegal adoptions from Sri Lanka which took place over three decades beginning in the 1970s to determine whether some of the children involved were victims of enforced disappearances and other offences. The office, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances (CED), also said Switzerland should guarantee the right to reparation for the victims.

The recommendations followed the committee’s review of Switzerland’s implementation of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Switzerland ratified the convention in 2016. Swiss officials are expected to report on the committee’s recommendations by May 7, 2022.

An enforced disappearance is the arrest or abduction of a person followed by a denial of the deprivation of liberty, or by the concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the victim. This practice places the disappeared outside of the protection of law and inflicts a heavy psychological burden on their families.

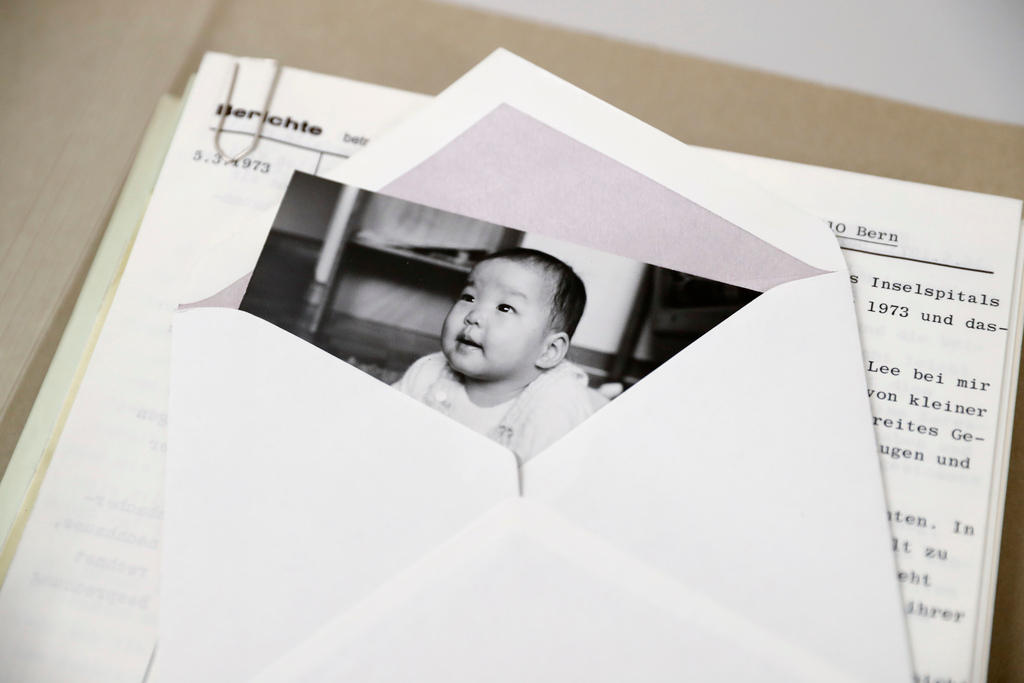

In December 2020, the Swiss government acknowledged and expressed regrets about the misconduct of authorities that were aware of and failed to prevent illegal adoptions from Sri Lanka in Switzerland from the 1970s to the 1990s. The irregularities were detailed in a historical report published in February 2020 by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW). It found that more than 700 children from Sri Lanka were adopted in the 1980s in Switzerland, some of them illegally.

Regarding illegal adoptions, the Swiss government pledged to help those concerned with the search of their origins. It intends to conduct another historical investigation to determine whether irregularities in adoption rules also occurred with other countries of origin. An expert group will examine the current adoption system to check if weaknesses remain.

Olivier de Frouville, vice-president of the UN CED, told SWI swissinfo.ch how the connection between trafficking of children and enforced disappearances was reported “for the first time, very clearly”, and how it could inform the committee’s work in the future.

SWI swissinfo.ch: How did you decide to review the illegal adoptions from your committee’s perspective?

Olivier de Frouville: In the case of Switzerland, we did not expect this issue to come up before our committee. It was a Swiss NGO, Back to the RootsExternal link, which presented, as is their right, a report to the committee in advance of the dialogue with Switzerland.

SWI: When are illegal adoptions considered enforced disappearances?

O.d.F.: The circumstances are varied. But there are some circumstances which are indeed of concern and which overlap with enforced disappearances. There is a certain number of cases where children have been appropriated and there has been a subsequent falsification of their identity. Either the children were forcibly disappeared, or they were stolen while their guardians were themselves disappeared. In some cases, they were born during the enforced disappearances of their mothers, and subsequently removed and illegally adopted.

There are many stories of women who gave birth, and their baby was taken away. They were then told by the medical staff that the baby had died, but they could not see the body. The baby had in fact been stolen and sold to intermediaries in Sri Lanka, who then gave it up for adoption to Swiss families. There are also stories of “baby farms”, where women were deprived of their liberty and forced to give birth to children who were then appropriated. In several cases, intermediaries in Switzerland arranged the placement of Sri Lankan children for adoption in Switzerland. To operate, these had to be authorised and monitored by cantonal authorities. The federal authorities had the right to appeal against the authorisations delivered by the cantons.

The report of the Federal Council recognised that both the cantonal and federal authorities failed to take appropriate measures to prevent several illegal adoptions, including through Swiss intermediaries, even though, since the beginning of the 1980s, the Swiss embassy in Colombo had been sending reports on illicit practices in Sri Lanka linked to international adoptions.

SWI: What was the Swiss delegation’s response to your committee’s remarks?

O.d.F.: We raised the issue with Switzerland based on the facts that were presented to us by this association [Back to the Roots]. And Switzerland responded that the process had already begun to try to clarify the facts [Federal Council report on Ruiz Postulate 17.4181External link]. They admitted also that some of those cases, not necessarily all those cases, may have resulted from enforced disappearances in the sense of the convention. I think the Swiss authorities are taking this issue very seriously and, even more importantly, are working in close consultation with the victims themselves. We are hopeful that we will receive good news when Switzerland reports to the committee in May 2022.

SWI: What are Switzerland’s obligations under the convention?

O.d.F.: The convention applies to all the cases that fall under the definition of enforced disappearances. We welcome the adoption by the Federal Council of the report in response to the Ruiz Postulate. We take note of the fact that the report acknowledges and expresses regrets about Switzerland’s failings. But we also say that we are concerned that Switzerland does not seem to be considering taking steps to prosecute the perpetrators and to recognise the victims’ right to reparation. So, we recall [Switzerland] that all state parties have an obligation to investigate and punish the perpetrators, and also an obligation to provide reparation to the victims. We also say that victims have the right to the truth, and the state has a duty to assist them in their search for truth, including through cooperation with countries of origins like Sri Lanka, which is also a party to the convention.

SWI: How will this case impact the work of your committee?

O.d.F.: I think for us, it’s clearly a new frontier. Previously, we had looked at the practice of illegal adoptions in other contexts; generally, periods of armed conflicts or dictatorships, like in Argentina or even in Spain during the Franco era, when thousands of babies were abducted to be raised according to the regime’s ideology. Abduction and appropriation of children also took place in contexts of repression against civilians or even in the context of colonial or post-colonial genocides like in North America or in Australia.

Here, we are facing another type of illegal adoption as enforced disappearance, which is rather connected to organised crime with few to no political motives, although sometimes there’s a thin line. It is clear that such illegal adoptions are plaguing many countries. Currently, these practices are generally observed through the lens of private international law and the regulation of intercountry adoption (1993 Hague Adoption Convention), the rights of children (UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and its Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography) but also trafficking (UN Trafficking Protocol and other regional instruments).

Enforced disappearance brings a new dimension to the issue. There is potentially a huge number of victims. So, our duty is firstly to work in close coordination with other competent bodies that work under other legal frameworks. And secondly, to be mindful that not all cases may fall under the scope of enforced disappearances. With that being said, I think our perspective can bring a lot to strengthen the rights of victims to truth, justice, and reparation. Also, criminals that profit from stealing children from their families and selling them domestically or abroad, should be aware that enforced disappearance is a very serious crime, and may even be, under certain conditions, a crime against humanity. It is also a continuing crime, in the sense that it continues after the abduction until the disappeared has been found. Therefore, it may be punished years after the abduction took place.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More

Global treaty: Defending the disappeared

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.