Viktoriia and Polina are now living with me

Viktoriia Bilychenko and her daughter, Polina, fled from the southern Ukrainian city of Mykolayiv to Switzerland and now live in Bern, 2,500 kilometres away. Their everyday life has changed radically, mine only a little.

Viktoriia, 34, and Polina, 10, arrived in the Swiss capital at the end of March, carrying only two bags and two backpacks. A Swiss Civil Defence employee brought them in the car, dropped the luggage in the house and said goodbye.

After the war broke out, I contacted the Swiss Refugee Council. The human suffering, the people fleeing and the images of the immense destruction resulting from this despicable attack by Russia on its sovereign neighbour shook me to the core. Hanging Ukrainian flags out of the window and posting doves of peace is all well and good, but in the face of this wretched war it didn’t seem enough for me, enjoying a comfortable retirement in rich and peaceful Switzerland.

When I got the call from the Federal Asylum Centre in Bern asking if my offer was still valid, I was a bit shocked. Can I do it? Do I want to? Then I made up my mind and accepted. And now they are both here.

They unpack their belongings, and Viktoriia brings two teacups, cutlery and a tea towel from her home in Mykolayiv into the kitchen in Bern. “A piece of home for Polina,” she says in English.

After the first night in my house, Viktoriia stands in front of me and says: “I miss my husband.” Her husband, a puppeteer at the municipal theatre in Mykolayiv, had to stay behind, like all Ukrainian men aged 18-60. Her brother and mother-in-law are also still there. Her mother, who lives in Poland, advised her not to stay in Poland; with the country hosting more than two million refugees, there is hardly any accommodation left. So after a four-day journey via Warsaw and Vienna, Viktoriia and Polina ended up in Bern.

From office to office

After four days, Polina has slept in her own room for the first time. She draws me a picture with high mountains and a hut. It looks like the Swiss Alps, where she has never been.

After a week in Bern, my “charges” are granted protection status S. And since Viktoriia’s salary is not enough to live on here, we go to the asylum social service, join a long queue and get upset about the queue-jumpers, who apparently also exist among Ukrainians. The next day we open an account at PostFinance, then we go to the migration police and the school office. After the spring holidays, Polina will join an intensive German class together with two Ukrainian children from the neighbourhood.

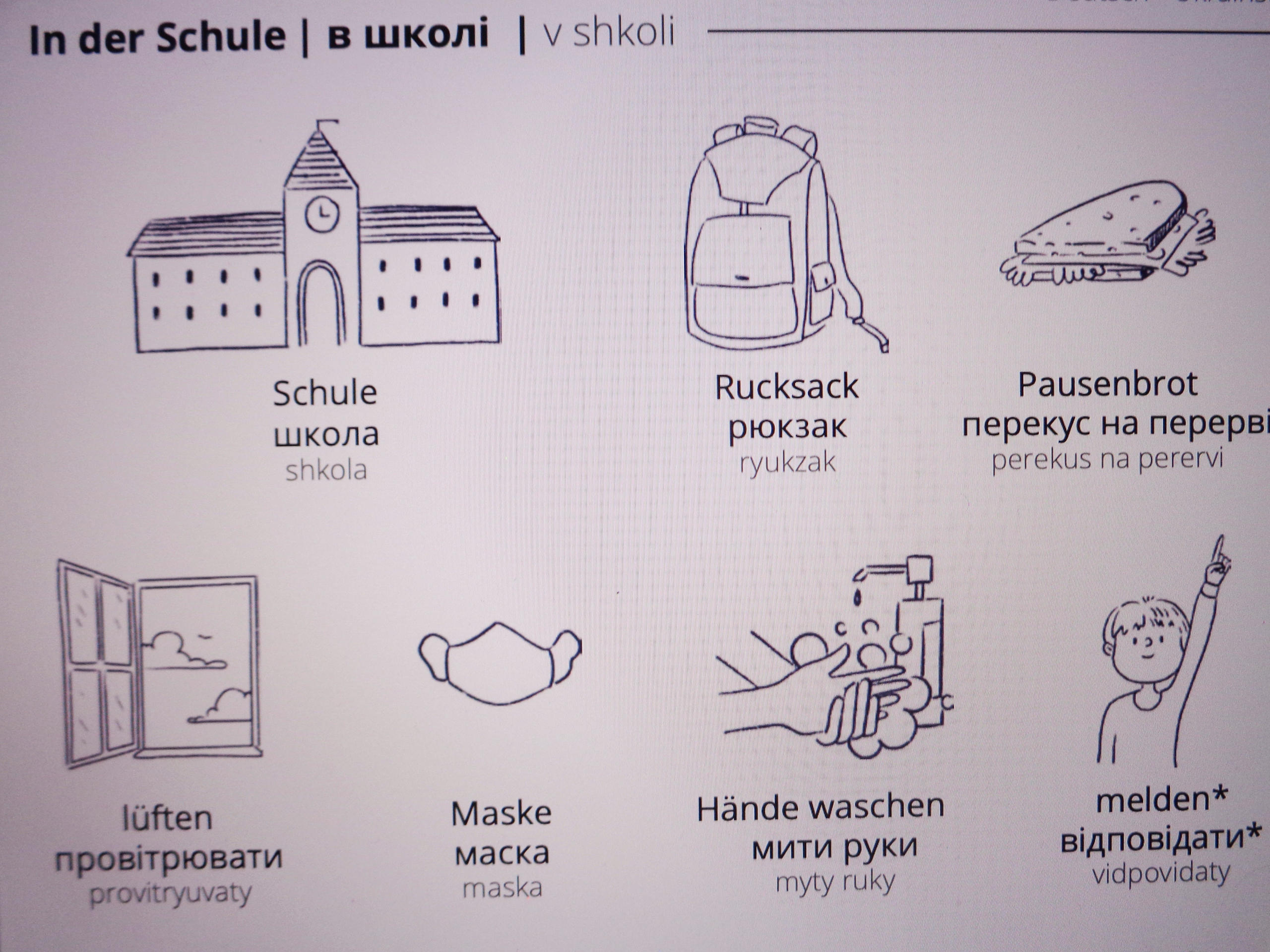

Slowly, something resembling everyday life returns: Viktoriia works as an IT coach for a Canadian company and sits at her computer during the day, no longer in Mykolayiv but in Bern – a digital nomad, so to speak. Her daughter is taught online. However, the number of lessons is steadily decreasing. Of the 33 children, only ten are still there because of the turmoil of war. So from time to time I teach Polina a bit of German, with the help of memory cards, pictograms and Google Translate.

Culinary differences

The smell of meat is spreading in my veggie household – Ukrainian cuisine is meat-heavy and hearty. The fridge is already fuller. The huge selection in the supermarket, for example of yoghurt, chocolate and much more, is too tempting for them. There is also more plastic waste than before.

But who cares? Viktoriia and Polina were catapulted out of their everyday lives virtually overnight and have to fear for relatives experiencing the constant terror of bombs and who have had no running water for days. A colander stored in the wrong place isn’t the end of the world.

Translated from German by Thomas Stephens

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.