Wanted: politically convenient definition of ‘neutrality’

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Switzerland is in search of a new interpretation of its neutrality. An international comparison shows that neutrality has many guises.

During peace talks Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly demanded that Ukraine become neutral – thereby removing its chances of joining defence alliance NATO.

Pascal Lottaz, a Swiss researcher who focuses on neutrality studies, is convinced that the aim of this suggestion is to achieve the neutralisation of Ukraine. “It’s similar to what happened to Switzerland in 1815 [when it regained independence]. The only difference is that’s what Switzerland actively wanted,” he says.

Earlier this year Ukraine proposed adopting neutral status in exchange for security guarantees from other countries, preferably NATO states. “At this point, the peace talks stalled. Russia doesn’t want that as security guarantees would amount to NATO membership,” Lottaz explains.

More

Inside Geneva: Neutrality, NATO, and the new world order

When European powers finally recognised Switzerland’s “perpetual neutrality” at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Swiss government did not receive guarantees of protection from other countries. And the fact that Switzerland is not a NATO member state means it is the sole security provider for its people.

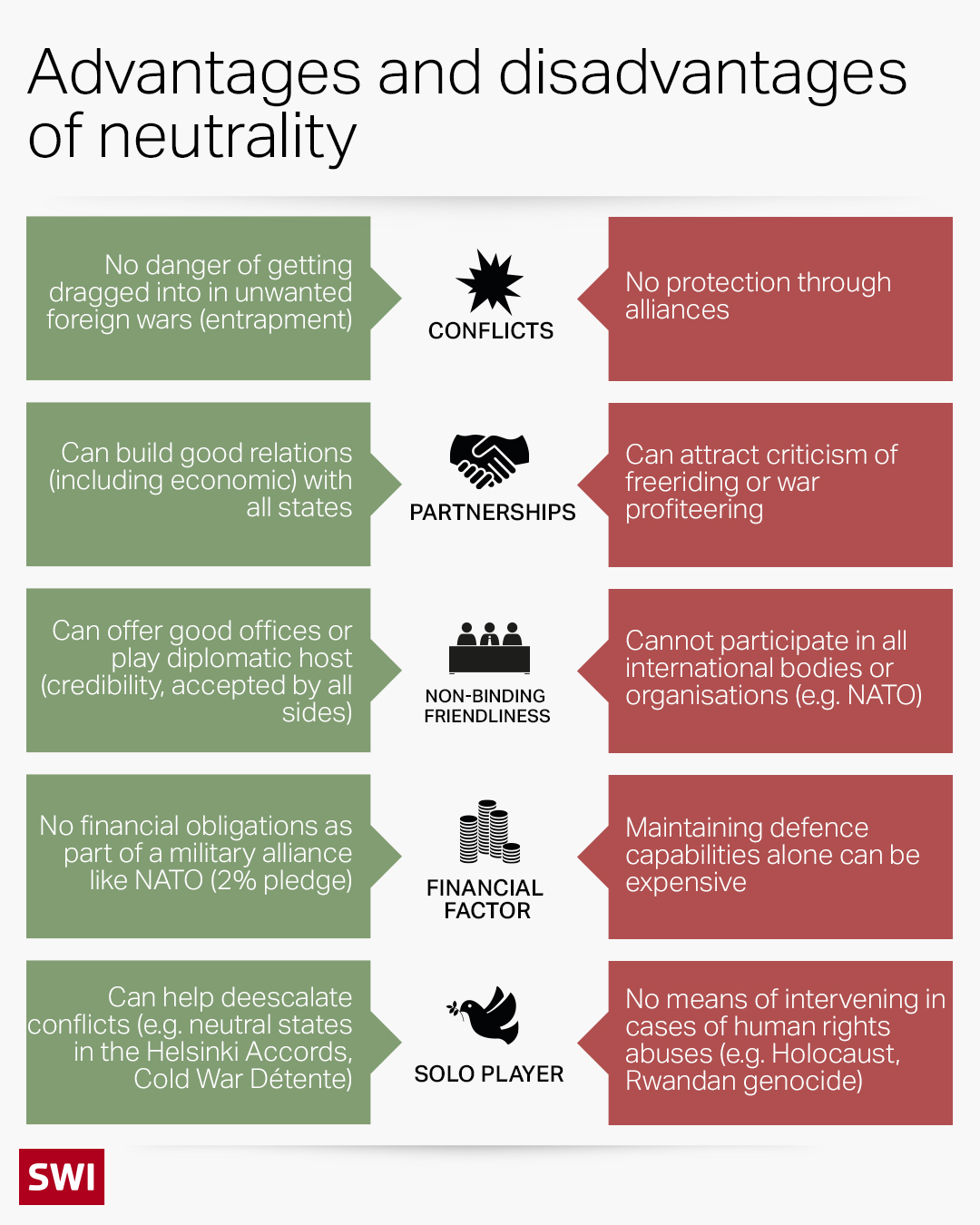

Neutrality has many facets to it. Governments and organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the United Nations have their own different interpretations of it. Neutrality can be self-defined, or it can be imposed upon a country by other governments. But no matter how countries became neutral, they have always been an effective buffer in conflict zones between superpowers.

Types of neutrality

Most neutral states have strong armies to defend themselves and keep foreign troops out.

States such as Costa Rica, Liechtenstein and the Vatican have adopted “unarmed neutrality”, which means they do not have their own military defence. Costa Rica counts on the US for protection, Liechtenstein hopes that Switzerland will come to its aid, and the Vatican is a special case altogether.

Some countries choose to be neutral just to isolate themselves from the international community. “Turkmenistan, for example, uses its neutrality to stay out of international alliances and make sure nobody interferes in its domestic affairs,” Lottaz says. Myanmar did the same until ten years ago and so did Albania during the Cold War.

Other countries, such as Switzerland and Austria – and Sweden and Finland before they recently applied for NATO membership, use their neutrality to play a role on the international stage and promote their good offices. They have an integrated approach, according to Lottaz.

“Sweden and Finland lost their neutrality status a while ago. They are now considered to be non-aligned, but if they joined NATO, it would put an end to their neutral status” he says.

Lottaz believes that the loss of neutral states could fuel the conflict in Ukraine and upset Europe’s stability. Even though he is happy that the debate about neutrality has been rekindled at home and abroad, he hopes as many countries as possible will remain neutral. In his view, this would contribute to the de-escalation of conflicts.

“However, the trend at the moment is anti-neutrality. Some Western governments consider Switzerland’s neutrality as support for Russia and therefore morally unjustifiable,” he says.

‘Situational neutrality’

Some analysts and politicians call the gradual disappearance of neutral countries a turning point, while others speak of a new Cold War which calls for the revival of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).

This alliance was established in Belgrade, having been initiated by Egypt, India and the former Yugoslavia during the first Cold War. It comprised 120 mainly African and Asian countries that remained neutral during the simmering East-West conflict and were not aligned with any major power bloc. Under pressure from Russia, Ukraine joined the alliance in 2010 only to leave again in 2014. The NAM still exists but has not been particularly relevant since the end of the Cold War.

More

“It has regained significance and could be revamped just like NATO reinvented itself because of the war in Ukraine. The dynamics have changed again,” Lottaz says, pointing out that the lack of such a union enabled China, India, Indonesia, Ghana and some South American countries to refuse to sanction Russia.

Even though they don’t use the term officially, India and China have maintained “situational neutrality” in the war in Ukraine. It means they take a neutral stand only in the face of a particular aggression and may not remain neutral in other conflicts like perpetually neutral countries would do.

The position of India and China on the war in Ukraine is similar to the US’s stance towards Europe during the Second World War. For the first two years the US followed its 150-year tradition of remaining neutral in European wars. However, this ended in 1941 when Pearl Harbor was attacked and they entered the Second World War.

“The US of the 19th century can be compared to the China of today,” Lottaz says. “China isn’t looking to join a military alliance. It’s not happy about the war in Ukraine, but it doesn’t want to be involved in any war. Only if the country in question were Taiwan would China be ready to wage war.”

According to Lottaz, superpowers have always been able to adopt neutral positions in different situations. He says this situational neutrality was instituted by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 which focused on the big powers and did not give smaller nations such as Austria and Switzerland much thought.

“For this reason, the law on neutrality is very liberal. It allows neutral governments to buy and sell weapons as long as they treat all warring parties equally,” he says.

Lottaz calls the Hague Conventions outdated as they have been amended only a few times since 1907. For example, cyberspace and missiles did not exist back then and were not included in the neutrality law. “The Conventions have to be updated to reflect the realities of the 21st century,” he says.

Flexibility of Swiss neutrality

Researcher Lea Schaad, an expert in security issues, claims that many Swiss do not know the difference between neutrality law and neutrality policy. While neutrality law forbids neutral countries to engage in armed conflict, neutrality policy solely requires neutral countries to convince other nations not to engage in a war. This makes neutrality policy a lot more flexible than neutrality law.

Pascal Lottaz says that Switzerland has also been rather flexible when it comes to its own neutrality. When Switzerland was a member of the League of Nations between the First and Second World Wars, it pursued “differential neutrality”, which means it did not participate in military sanctions but joined economic sanctions. However, when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Switzerland was forced to switch back to “integral neutrality” as its southern canton of Ticino was severely affected by the economic sanctions imposed on Italy.

Schaad thinks the debate on neutrality was given a further boost in May when Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis coined the phrase “cooperative neutrality” at the World Economic Forum.

For Lottaz, terms like “active neutrality”, “committed neutrality” or “cooperative neutrality” are political and were created purely to repackage neutrality. Schaad agrees: “Maybe this marks the beginning of Cassis’s attempt to re-interpret neutrality.”

Both researchers agree that the flexibility of a neutrality policy results in the same discussions between the same sides. On the one hand, those with a traditional and strict understanding of neutrality require Switzerland to treat warring parties equally, both militarily and economically, which rules out the use of sanctions. “We’ve now reached a point where some want to return to integral neutrality,” Lottaz says.

On the other hand, those with a more relaxed understanding of neutrality do not want Switzerland to take an isolationist path; they want the government to take a more active position.

“It would be nice if we could clarify what our policy is,” Schaad says. “This would eliminate the endless discussions of how Switzerland should act every time there is a geopolitical event.”

Quicker Swiss reaction

A clear policy might be just around the corner because the government has announced a new report on neutrality. In the previous report, in 1993, the government outlined how it intended to define neutrality.

According to Schaad, the new report could lead to yet another interpretation, as happened after the end of the Cold War. “The changed geopolitical landscape today also requires a new interpretation of neutrality,” she says.

If and how Switzerland reinterprets its neutrality will be interesting for other countries. “There is the hope that Switzerland will be able to react faster,” Schaad says. When war broke out in Ukraine, Switzerland’s reluctance to adopt sanctions against Russia imposed by the US and its Western allies was criticised.

However, this government’s plan to give neutrality a new meaning could be scuppered by Christoph Blocher, a former government minister and billionaire figurehead of the right-wing Swiss People’s Party. He is planning to launch a popular vote to make strict neutrality an integral part of the Swiss constitution. Such an initiative would mean that the last word on Swiss neutrality would go to the Swiss people.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling/ts

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.