How Swiss minimalist houses launched a new building style

In the 1920s, architects belonging to the “Neues Bauen” movement began to build small, cheap houses for workers. In Switzerland, this style was controversial, and was seen as being Communist. But many of the movement’s ideas still prevail today.

After World War I, there was a housing shortage in Switzerland. As a result, architects belonging to the “Neues Bauen” (“New Building”) movement aimed to create cheap living spaces for the working classes, using efficient construction methods.

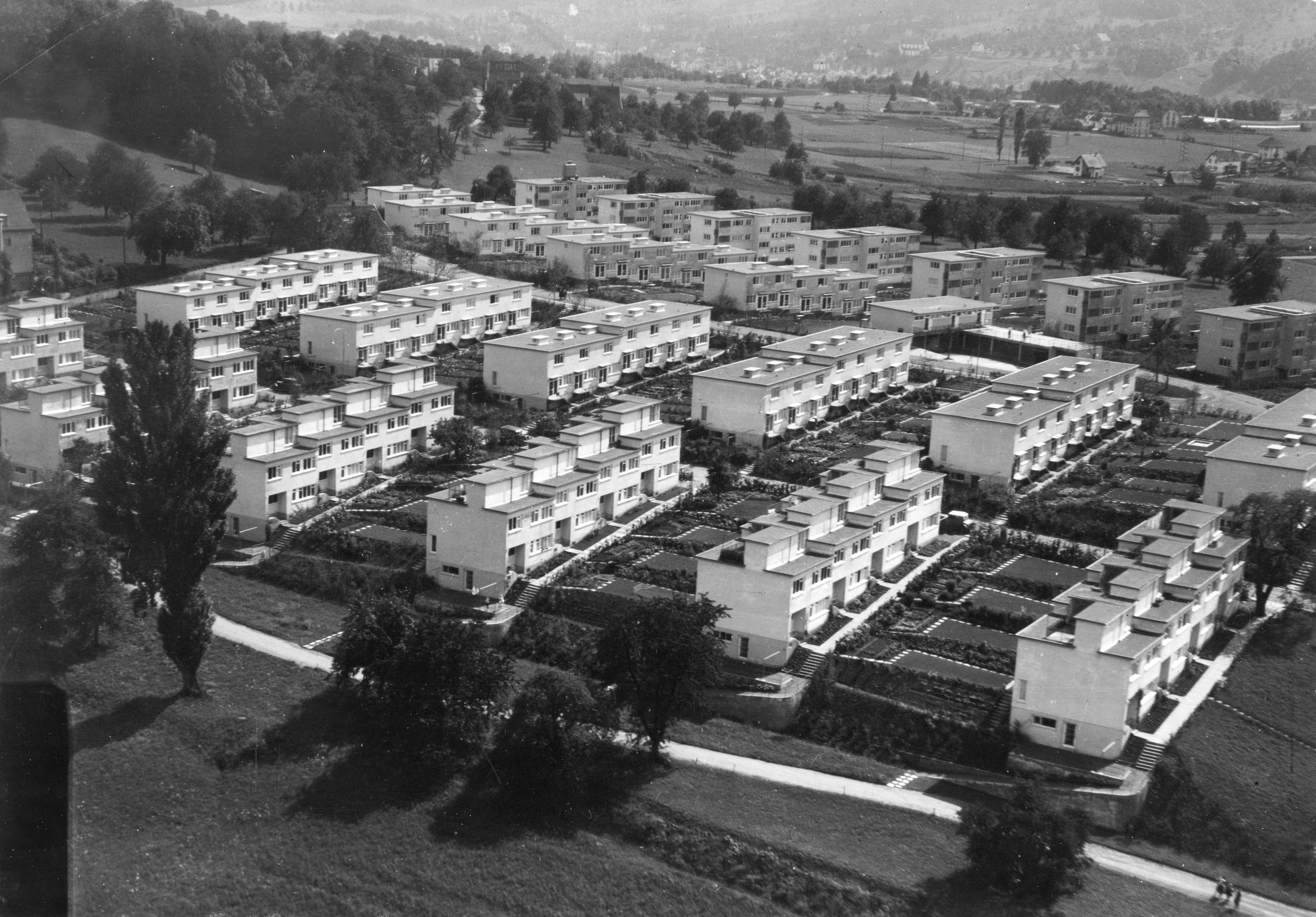

They designed small houses with flat roofs and no cellar to save on materials and building costs (land prices were not as much an issue as today.) The architects “industrialised” the construction process by using prefabricated parts and standardised prototypes for mass production. Some houses only had windows on one side, to save on long-term heating and repair costs.

In 1930, the Neues Bauen architects presented their ideas at the first Swiss Housing Exhibition (WOBA) in Basel, an exhibition that included a real residential estate.

“The Neues Bauen residential estates were conceived as a kind of outdoor exhibition,” says Martino Stierli, chief curator for architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York and a specialist in architecture and town-planning history. “To a degree, they served as a marketing instrument for the architects’ ideas.”

Each house offered a living space of 45 square metres and had its own garden. A low-income family could live there cheaply but comfortably. Every house had its own bathroom and kitchen – in those days, not a given.

‘Construction Bolshevism’

The style met with opposition in Switzerland. “Many Neues Bauen proponents combined utopian visions of society and socio-political questions with their architecture,” Stierli says. “Because these ideas were associated with the political left, they met hostility from the right.”

Rhea Rieben, a historian at Basel University, studied the reactions in newspapers of the time for her doctorate. “Right-wingers linked Neues Bauen to Communism. They said everything looked uniform and offered no scope for individuality. It was, they said, opening the gates to the Communists,” Rieben says. “Even the public subsidies were a gripe for the bourgeoisie because they thought these undercut the housing market.”

Newspapers of the day bandied about terms like “Marxist living culture” and “breeding grounds for Communists.” Some Neues Bauen architects were indeed socialists who later emigrated to the Soviet Union, Rieben says. “But the debate was politically loaded and only indirectly related to architecture.”

What remains of Neues Bauen?

Neues Bauen was not a success story; at the end of the 1930s, the method was phased out. Tiny terraced houses with gardens used up more space than apartment blocks. And the construction method was not as cheap as hoped.

However, Stierli says, “Neues Bauen never disappeared from memory”. Political developments in the 1930s led to a split, then the economic progress after the Second World War sparked an unprecedented construction boom. “Although the focus shifted from those living on the breadline, the architecture from the postwar era to the present can be viewed as a victory for Neues Bauen, which established itself as a paradigm in Switzerland,” he says.

Stierli cites housing cooperatives, which aim to create affordable accommodation for everyone, as an example. But other Neues Bauen concepts are still put into practice today; prefabricated building parts and housing and system and modular design increase efficiency and save costs. The idea of saving space has also to some extent been reborn in the so-called Tiny House movement.

The spirit of Neues Bauen also lives on in concrete form: an association in Basel plans to renovate one house in the residential estate according to the original design, including furniture and décor, then rent it to students and make it accessible to the public via tours.

Other Neues Bauen housing estates are still inhabited and are almost unchanged, such as the Neubühl estate or the Bernoulli houses in Zurich. In contrast, the Weissenhof estate in Stuttgart was part destroyed in the war, part demolished and part altered; one remaining house accommodates a museum.

An era of recession, housing shortages and homelessness followed the First World War. Defeated Germany, forced to pay reparations, was particularly hard hit. Inflation added to its woes. There was little money for building.

It was not until the roaring 1920s, between 1924 and 1929, that the economy was stabilised. This was the heyday of big Neues Bauen experiments, particularly in German-speaking countries.

The Wall Street crash in 1929, and the subsequent Great Depression enabled the rise of the Nazis, who launched investment initiatives and subsidised housing, but stifled architectural experiments. This political climate also affected Switzerland.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.