Why the Swiss are losing interest in cantonal votes

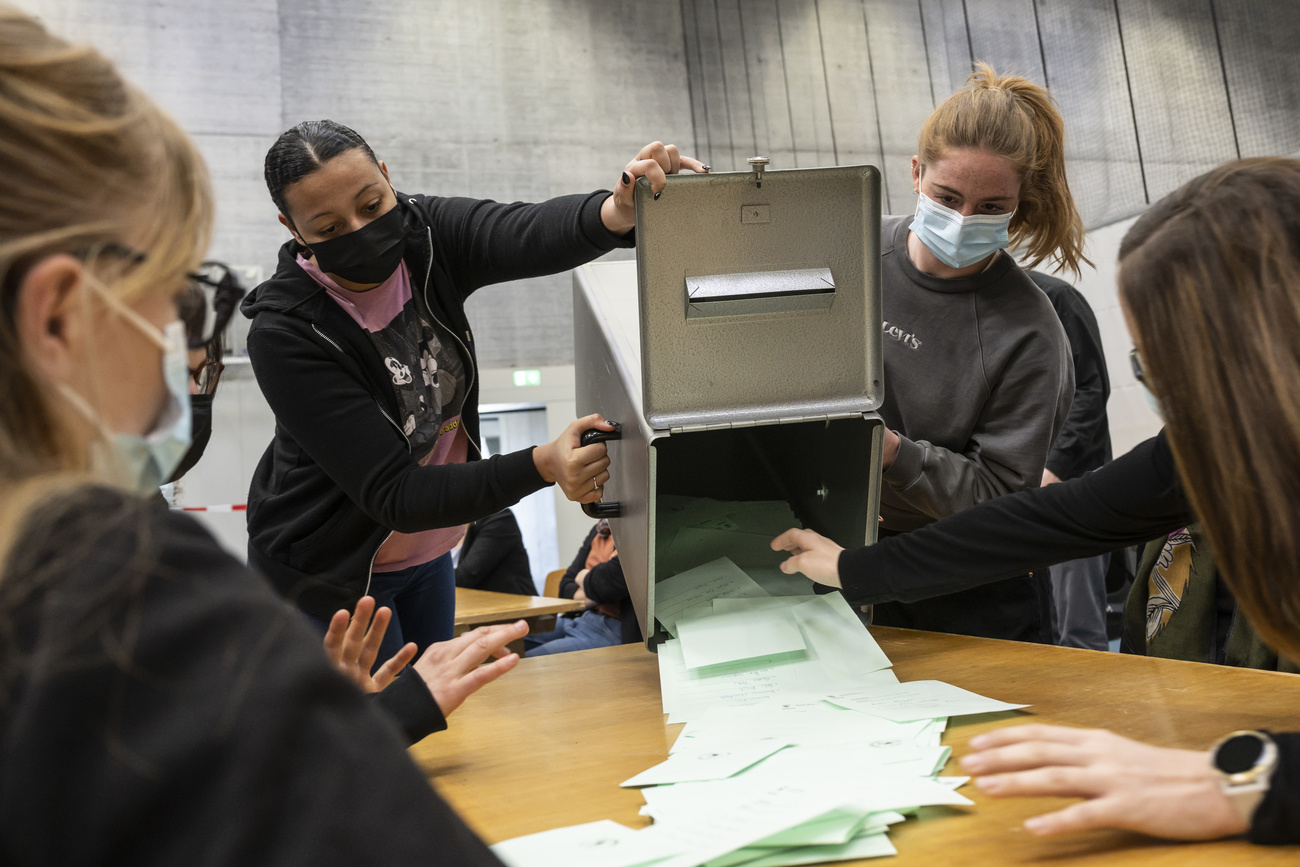

The turnout was dire in the most recent cantonal elections in Switzerland. Only 32% of the electorate dragged themselves to the polling stations in canton Bern this past March. This is an extremely low percentage – but it’s not atypical. What’s the reason for Swiss voter fatigue?

It may seem troubling that less than a third of the electorate in canton Bern bothered to vote in the local government and parliament elections earlier this year. What’s even more concerning is that nobody seemed surprised by the low turnout. It was expected.

Research has shown for some time that the Swiss no longer form an opinion on everything and everyone. It would be impossible to expect them to do so given the sheer number of elections and popular votes held each year at federal, cantonal and municipal levels. The Swiss no longer feel obliged to participate in political life. They see it as a right they can bring to bear when it suits them.

There are three types of voters: those who vote regularly; those who vote occasionally; and those who never vote. Statistically speaking, three out of ten people always participate in popular votes, while five vote occasionally and two never go to the polls. To state the obvious, people will vote if an issue concerns them greatly or interests them, or if they hold a strong opinion about it.

De-politicisation vs re-politicisation

Looking at how turnout in popular votes and elections has developed over the past 30 years, we can identify two significant but opposing trends: de-politicisation and re-politicisation.

The big, overarching issues have re-politicised the electorate. In the 1980s, the Swiss voted on preserving forests. More recently their main concern was the pandemic. Other past popular votes that stirred the electorate were EU membership, immigration and climate change.

The common denominator is that none of the traditional political parties gave these issues the attention they deserved when they first emerged. By the time an issue made it to the polls, people were already staging street protests. The parties that had recognised and addressed these challenges fared best at the ballot box, as was the case for the right-wing Swiss People’s Party and the Green Party.

In 1995, national turnout hit rock bottom, when only 42% of eligible voters participated in federal elections. Ten years later, this number stood at 49%. In contrast, the average turnout for all elections across Switzerland has seen a continuous rise since the 1980s – from around 40% to today’s average of 49%.

In exceptional times such as the pandemic, participation in national votes has been 57%, rivalling what it was after the Second World War. But what about cantonal elections? No comparative figures were available until Sean Müller, assistant professor of Swiss and comparative federalism at University of Lausanne, researched the matter.

Müller’s data shows that the average turnout in cantonal votes is also affected by re-politicisation. As in federal elections, turnout has steadily increased since the 1980s, when it was 35% – it now stands at 42%.

But when it comes to cantonal elections, it’s a very different story. Forty years ago, the average turnout was 55%; today it is a mere 40%. The trend continues downward, which is a clear indication that the Swiss are indifferent to who governs and shapes their cantons.

A country of commuters

Recent surveys show that the Swiss no longer strongly identify with their cantons. That’s in large part due to their increased mobility and the fact that many Swiss commute to the bigger towns for work. Some live in places that are not especially familiar to them.

Something called “glocalisation” (a combination of globalisation and localisation) has popped up, particularly in central Switzerland. It means people are either interested in global or national issues or, at best, what’s happening right at their doorstep – in their neighbourhood or community – but but not in their canton.

Everything that falls between global and local seems to have lost its importance, and that’s especially true for cantonal politics. Many Swiss no longer believe that a canton alone can make a difference, which is partly why only loyal, regular voters participate in cantonal elections.

Higher turnout in homogeneous communities

Remarkably, in peripheral areas or alpine regions where people speak their own language, cantonal elections remain a significant part of people’s regional identities. This is reflected in high voter turnouts in local elections in Italian-speaking Ticino and Valais. But in central Switzerland, canton Lucerne has seen a drop in turnout, driven by voters from the Lucerne agglomeration.

Political scientists have concluded that turnout is usually higher in closed homogenous communities. In regions where these kinds of communities no longer exist, it mainly boils down to competition among political parties or media attention motivating people to go to the polls.

Often cantonal elections do not set the political course. They are merely democratic rituals or simply a confirmation of the Swiss people’s right to vote. As a rule, incumbent politicians are re-elected, and vacant seats in parliament go to members of the incumbent parties. This does not make a catchy media story or provide the general public with enough reasons to cast their votes.

The media are an important driving force in election campaigns. They often run better advertising campaigns for candidates and parties than the parties themselves. But due to the tough times local media outlets are experiencing, their advertising budgets have been cut. Studies conducted by political and media scientists have shown that research, election leaflets and critical journalism have become scarce. And once the media cuts its political reporting, public participation suffers, especially in elections.

Swiss Super Sunday?

One solution, however, holds some promise – and that’s to hold cantonal elections nationwide on the same Sunday. Every four or five years, regional media could make a concerted effort on “Super Sunday” and parties could run their election campaigns across the regions. Such coordinated cantonal elections would benefit people who work in canton A and live in canton B, as they are affected by the election results in both places.

But let’s go back to our initial question. What happened in canton Bern during the elections in March? The people of Bern cherish their democratic rights even though they are not showing up at the polls. They offer an extreme example, but it is not a one-off. It is happening elsewhere too.

The distribution of seats in the cantonal council hardly changed. “Everything remains the same” was the motto of the elections, which could have been one of the reasons why the turnout was so low. The second reason could be that most journalists who cover canton Bern live in Zurich, which dilutes their interest in Bern elections. The third reason could be that most residents of canton Bern live in the centre, where mobility is high and regional attachment is low.

Taking all of these facts into account, a turnout of 31 or 32% is actually not that bad.

Translated from German by Billi Bierling, gw, ds.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.