Why voting by mail is rarely easy

Faced with having to go to crowded polling stations during a pandemic, voters – and political campaigns – are increasingly turning to postal ballots. But the cases of the United States, Poland and Switzerland show that introducing and maintaining this way of voting is full of potential pitfalls.

As an eligible Norwegian citizen taking part in a popular vote, you need a piece of paper, three envelopes and a valid stamp. On the white paper you write down your choice (name of party or candidate, yes or no in a referendum), mark the first envelope as the “voting” envelope, add some personal information (name, date of birth, address) on the second one and finally address the third to the election commission of your registered home municipality. Layer the envelopes, apply the stamp and put it in the post – that’s it.

While the Norwegian way of postal voting is probably the most liberal in the world, it is far from the only one on offer. More than 50 countries allow remote voting in elections and referendums. This was the case even before the Covid-19 pandemic, which made remote voting almost a necessity for a safe procedure.

As a result of the pandemic “at least 70 countries have postponed their scheduled public votes”, says Nana Kalandadze at International IDEA, an intergovernmental democracy support agency which monitors elections and referendums around the world.

In addition to safety concerns over the voting process itself, many of the places that cancelled votes cited the inability to carry out campaigning or public debates as reasons for their decisions. But at least 56 countries did hold votes despite the pandemic – often through hastily arranged postal voting schemes.

“Some countries are now trying to quickly introduce some form of mail-in voting, but such moves are full of obstacles and pitfalls,” Kalandadze says.

United States: presidential attacks

In the United States, postal or absentee voting goes back to the 1880s and is now available to 83% of American voters across all states. Twenty of the 50 US states have made it easier to vote remotely in this year’s presidential election because of the pandemic.

More

Swiss and US democracy: twins separated at birth?

According to ERIC, a non-governmental election watchdog, the rate of possible cases of voter fraud – such as double voting or voting on behalf of a deceased person – has been 0.0025%, or 376 ballots out of 14.6 million ballots cast by post in the US.

But the pandemic has triggered a hyper-partisan debate over postal voting driven by the sitting president, Donald Trump, and the ruling Republican party.

Trump tweeted in July that “The 2020 Election will be totally rigged if Mail-In Voting is allowed to take place, & everyone knows it”. It’s one of more than 70 attacks he has made against voting by mail since March.

With his crusade against mail-in voting, Trump is “complicating Republican turnout efforts in numerous key states like Pennsylvania, Ohio and Iowa,” says Amy Gardner, a national political reporter at the Washington Post. That’s because many older voters, who tend to vote Republican, are unlikely to want to go to the polls in person as the coronavirus continues to spread.

Joe Mathews, a Los Angeles-based democracy correspondent, believes that by questioning postal voting, “the president wants to undercut the electoral process as such by laying the groundwork to claim that the election was rigged if he loses in November”.

Poland: last-minute attempt

Postal voting also became a bitterly partisan issue in Poland, which had no postal-voting rules at all until recently. As the pandemic’s first big wave hit in April, the Polish government was eager to see President Andrzej Duda (from the ruling populist Law and Justice Party) re-elected. It decided to go ahead with its presidential election on May 10, but the lockdown and a ban on large indoor gatherings made in-person voting impossible. So the government tried to fast-track a new electoral law allowing all-postal voting.

“Basically everything was done wrong,” says Magdalena Musial-Karg, professor of political science at Poland’s Adam Mickiewicz University. Eager to secure victory in a contentious election, the government tried to bypass the National Election Commission in launching the postal vote, she adds.

Such a change during an ongoing election process is prohibited by European Union law, and the Polish postal service tasked with delivering the ballot papers lacked the addresses of millions of eligible voters.

In the end, the May 10 ballot was postponed at the last minute through intervention by the National Election Commission. It was rescheduled for two rounds of votes in June and July, when Duda claimed a narrow victory over his challenger, Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski.

Musial-Karg and a colleague recently published an accountExternal link of Poland’s partisan attempt to fast-track postal voting, in which they noted that “it took Switzerland 30 years to test and develop postal voting, whereas Poland tried to do it in just two months”.

Switzerland: accusations and increased turnout

Indeed, Switzerland offers the most extensive record of postal voting in the world, because its citizens vote multiple times a year in regular referendums. But the Swiss tradition of voting by mail is much younger than that of the US: it dates to the years following the introduction of universal voting rights for women in the 1970s.

“At first only sick people were allowed by law to mail in their votes,” recalls Hans-Urs Wili, who led the political rights section at the Federal Chancellery for many decades. But in the 1990s a parliamentary initiative opened the door to a much more liberalised postal voting operation. Today, more than 80% of all ballots in elections and referendums are sent by mail, according to the Swiss Post.

During his tenure as justice minister, right-wing icon and former Swiss People’s Party leader Christoph Blocher repeatedly claimed to the Chancellery that postal voting was “wildly faked”. In 2006, he ordered the government to send out a federal circular to all cantons mandating a series of precautionary measures. For example, all postal vote envelopes had to have the disclaimer: “Anyone who does not want to exercise their voting rights must tear up their voting card before disposing of it!”.

However, the cantons were ultimately able to show that the allegations of fraud were unfounded, and the federal order became non-binding a year later. But its withdrawal was never officially communicated to the public.

Wili says the introduction of postal voting has contributed to an increased average voter turnout of 15% nationwide and has doubled turnout in canton Geneva.

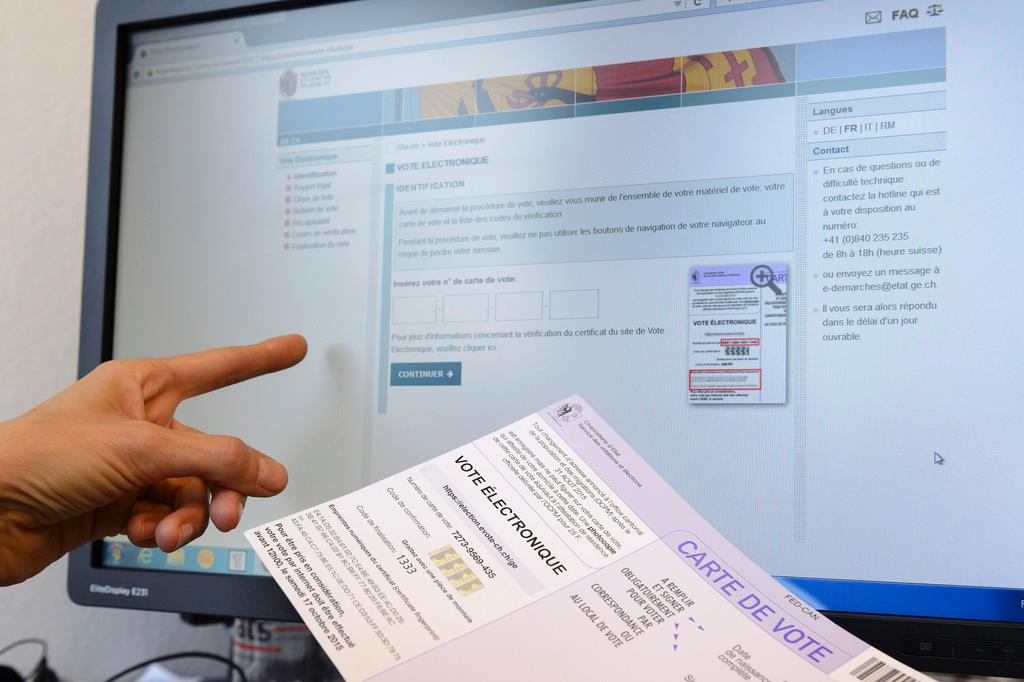

As in the United States, voter fraud is extremely rare in Switzerland: in more than 40 years of regular ballots, officials have registered just five attempts to manipulate the vote on a local level. And as in the US and many places around the world, the conversation about the best way to vote continues – most recently over the issue of electronic voting, a new frontier in the quest to cast ballots in safety, in secret and without manipulation.

More

The battle for the future of electronic voting

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!