Why voting in Switzerland is difficult for the visually impaired

The Swiss democratic system struggles to include certain groups of citizens. People who are visually impaired can participate in votes and elections in Switzerland, but they need assistance from another person, which compromises the secrecy of the ballot.

Regula Schütz sits at her computer reading a newspaper, or rather listens to the paper being read at high speed. “This is pretty slow for me,” says Schütz, who is visually impaired, with a smile.

She explains that she has actually slowed down the audio for the journalist’s sake and that she is listening to information about an upcoming vote.

While it is easy for her to obtain information on popular votes which take place in Switzerland up to four times a year, the actual act of voting is more difficult.

Swiss ballot papers are designed in such a way that the people who are visually impaired cannot fill them out on their own and therefore require assistance.

Swiss law and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Switzerland ratified in 2014, demand that people with disabilities are able to vote by secret ballot. The Swiss National Association of and for the Blind estimates that about 250,000 Swiss citizens are potentially affected.

When questioned about this, the Federal Chancellery told SWI swissinfo.ch that according to Swiss law a person is allowed to receive assistance if they are unable to vote independently.

People with physical or mental disabilities have to deal with certain discrimination in Switzerland. They are not allowed to vote at all, for example. The UN reprimands Switzerland about this on a regular basis. More than a year ago, Geneva became the first of the country’s 26 cantons to put an end to this form of discrimination.

More

Geneva grants full rights to mentally disabled citizens

Schütz finds it discriminating that she is not able to vote independently. This is despite the fact that she has many trustworthy friends who can help her.

But not everyone is so lucky, says Gianfranco Giudice, who is also blind. He says: “It’s a big problem finding someone I trust enough to tick the right box on the ballot paper. I have missed a few popular votes, as I couldn’t find anyone to help me.”

He highlights another stumbling block. “What if the assisting person makes a mistake that leads to my vote being null and void? I cannot control this.”

Schütz shares Giudice’s concerns. “Mistakes can always happen. I get annoyed if people do my shopping and bring back the wrong type of milk or butter. But mistakes are much more serious when they occur in votes.”

Not unique to Switzerland.

Every country that grants its citizens the right to vote must find ways that allow people with disabilities to participate in political life. Some countries have already found certain solutions.

“In Sweden, visually impaired people can vote for parties and maintain the secrecy of the ballot,” Henrik Götesson of the Swedish Association of the Visually Impaired told SWI swissinfo.ch.

“Ballot papers can be ordered in braille,” he explains. The only flaw is that without assistance, people who are visually impaired are unable to change voting lists or vote for individual candidates.

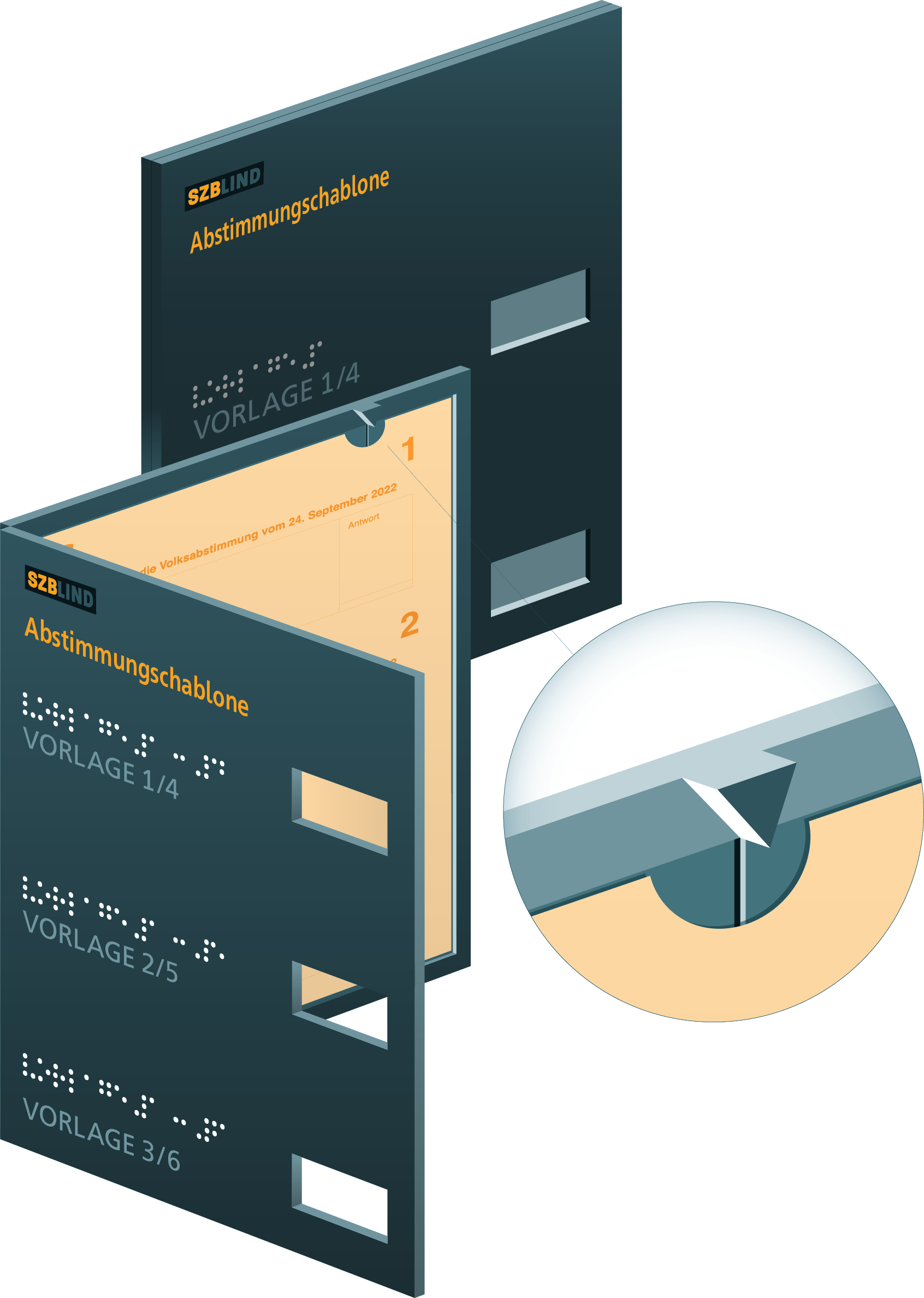

In his quest to give people who are visually impaired the same voting possibilities as everyone else, Götesson wants to introduce special templates. A ballot paper can be inserted and help voters find the space where they may write their response. See graphic below.

Such templates are already used in other countries such as Germany, Austria, South Africa and Canada.

Switzerland’s National Association of and for the Blind wants to follow this example, at least for national votes; it has developed a template for people who are visually impaired to vote without assistance. The association has contacted government officials and politicians to discuss a nationwide introduction.

The process is rather complicated. “Popular votes and elections are regulated by the cantonal authorities. For national votes, some of the cantons have designed their own ballot sheets which are adapted to their counting systems,” the Federal Chancellery explained in an emailed reply.

This means that a nationwide introduction of such a template is only possible if ballot papers are standardised across the country. However, this would need the cooperation of the largely autonomous cantons.

What do people who are visually impaired think about such a generic model?

“The templates are good for popular votes but too complicated for parliamentary elections,” says Schütz. Voters have great liberties in Swiss parliamentary elections. They can either keep the party list as stated on the ballot sheet, change the order, vote for a candidate twice, delete a candidate or merge candidates of different parties into one list.

“It’s better than nothing as a temporary solution. But I still wouldn’t know for sure if I inserted the right ballot paper into the right template and ticked the right box,” adds Giudice.

More

Courses should be ‘more accessible’ for visually impaired people

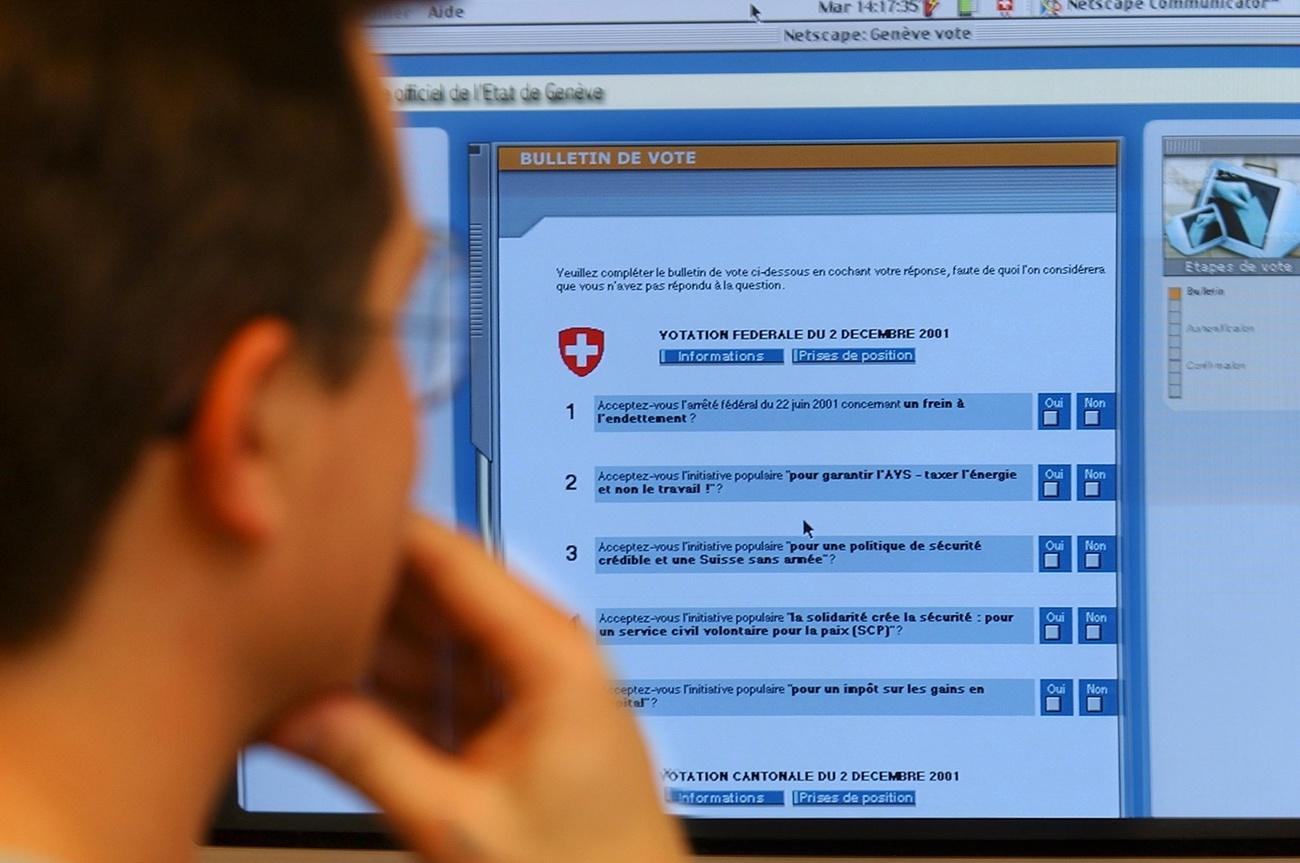

E-voting

In his opinion, e-voting would be the best solution. He notes: “E-voting could be offered to everyone, also to people without disabilities. This means it would not be a solution just for the blind.” Schütz agrees, saying that she doesn’t understand why this is not possible.

“E-voting could offer a holistic solution for popular votes as well as for parliamentary elections,” says Martin Abele of the Swiss National Association of and for the Blind. “As long as it is accessible to everyone, e-voting is the best fix.”

In 2019, the Swiss government came out against introducing e-voting due to security concerns.

Giudice disagrees with the decision. “We always talk about security and data protection but that’s absurd and contradictory. Postal votes are a lot less secure and compromise the secrecy of ballot for visually impaired people,” he says.

More

These are the arguments that sank e-voting in Switzerland

So far, most countries have been hesitant when it comes to e-voting.

“For the visually impaired, e-voting would be a good option, but from a political perspective it is unlikely to succeed due to security concerns,” says Götesson. “So far, I haven’t come across a perfect voting system for the visually impaired.”

But at least the Swiss Federal Chancellery has acknowledged the problem. “E-voting gives visually impaired people more autonomy when voting,” it stated. Pilot projects for e-voting should soon be possible again in the cantons.

Social awareness needed

But people with disabilities face much more serious problems. “I don’t feel represented in politics,” says Giudice.

“There is not only a lack of inclusion when it comes to votes. People with disabilities are underrepresented in our political life too,” says Chris Heer of the Organisation for People with Disabilities, Agile.ch.

“It should be obvious that people with disabilities are integrated into our society.”

Heer has a long list of measures he would like to see introduced in Switzerland: political parties should make their websites accessible for visually impaired people; sign language interpreters should be available at events for people with hearing problems; and ramps should be installed for people in a wheelchair.

Trying to find a way of including people with disabilities is often seen as a “form of social welfare”, according to Heer. But it’s easy to forget what it’s all about, liberal human rights, he adds.

More

Swiss disabled groups launch initiative for greater inclusion

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!