The Japanese ‘watch doctor’ who restores historic Swiss timepieces

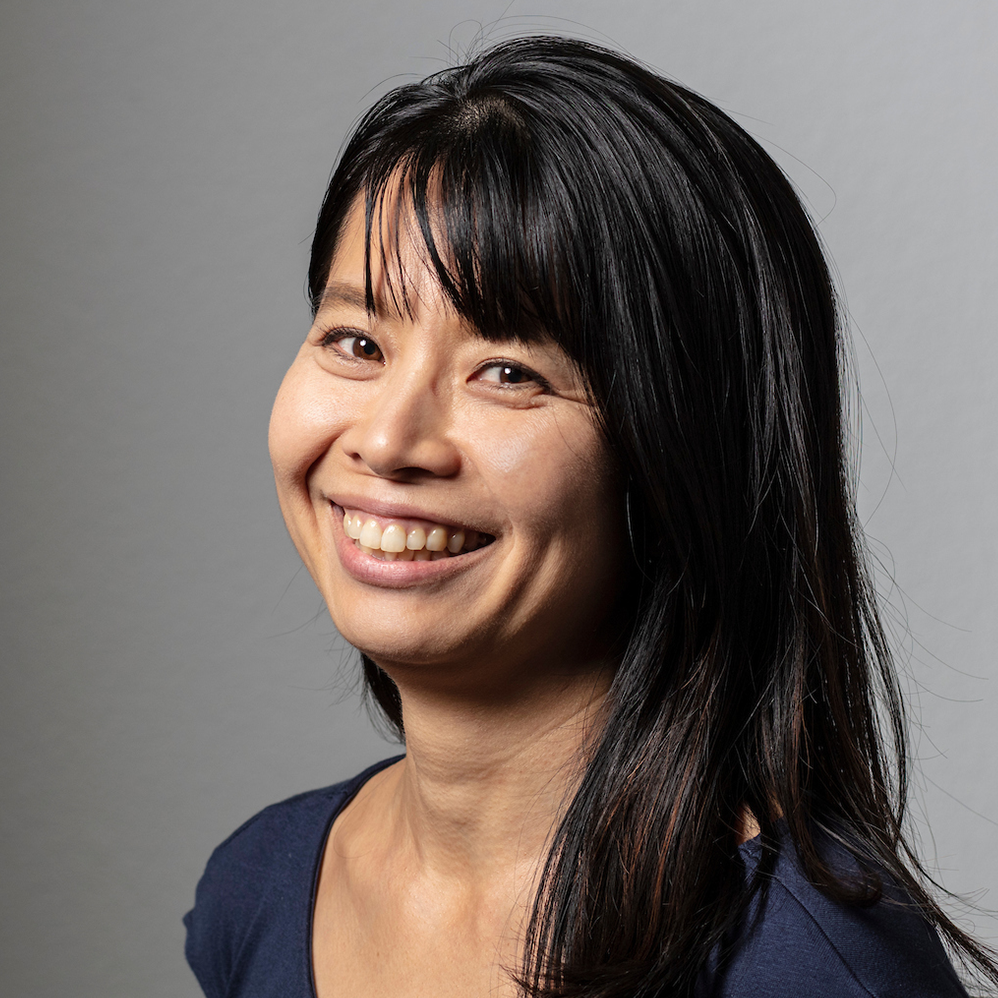

There is hardly a more 'Swiss' industry than the watch industry, but it is not only the Swiss who are masters of the craft. Masaki Kanazawa from Japan, for example, is forging a remarkable career in Western Switzerland's ‘Watch Valley’.

A documentary about Swiss watchmaking fascinated the then 17-year-old Kanazawa so much that he promptly decided to become a watchmaker himself. Today, 26 years later, he is a watch restorer at the Musée international d’horlogerie (MIH), or international clock-making museum, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a small town near the Swiss-French border which has been recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site for its watchmaking industry.

“I’m by no means the most talented person,” Kanazawa tells SWI swissinfo.ch. “But I think I’m the right person for the job of restorer. As a member of the museum team, I understand the vision of this museum very well, and I am committed to deciphering the timepieces and the techniques of the past that have disappeared and preserving them for future generations.”

The MIH’s collection includes numerous rare and coveted timepieces, including old water clocks, pocket watches from the 16th century, large wall clocks and mechanical watches. They vary greatly in size, type and date of manufacture.

Restoring historic timepieces

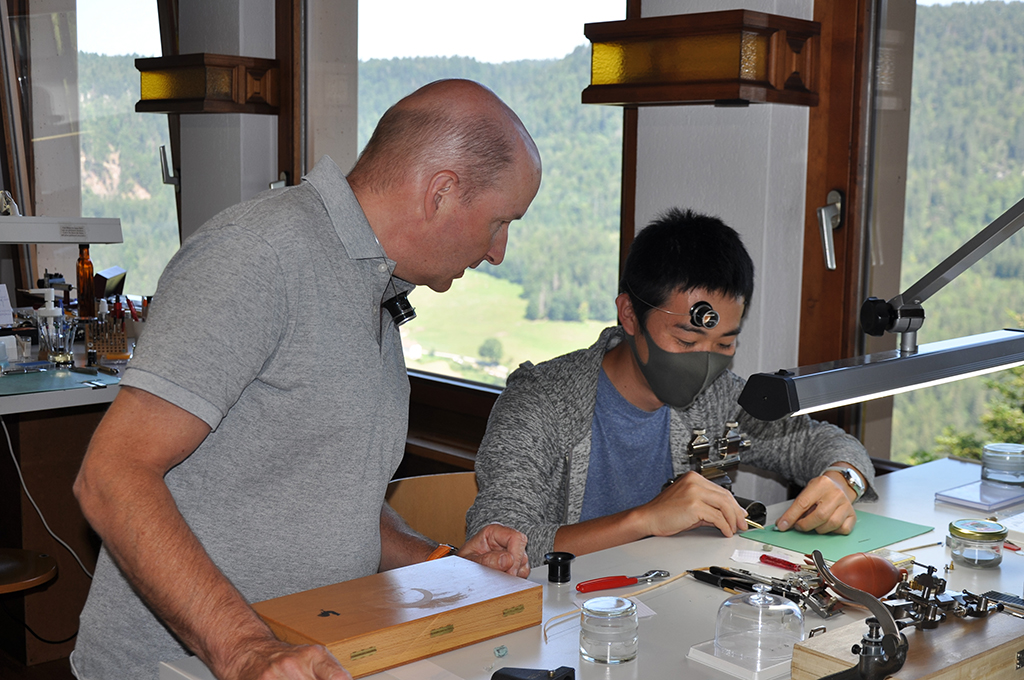

Restoration is a time-consuming process – in the last 11 years, Kanazawa has not even been able to restore 100 timepieces – but he is proud that timepieces with such rich histories have landed on his desk.

One of the most memorable items for him was a complex Ami Lecoultre pocket watch, which he worked on shortly after taking up his post as museum restorer. The watch was exhibited at the 1878 Paris World Fair, and despite its complexity and rarity, the museum director at the time entrusted it to him for restoration.

Kanazawa learnt his watchmaking trade in Switzerland. After graduating from high school in Japan, he moved to France in 1999 to learn French. He then enrolled at the watchmaking school in Le Locle, north-west Switzerland, where he graduated in 2004 as a watchmaker specialising in restoration.

He continued his training, earning the title of technician in restoration and watch finishing. This was followed by practical experience with independent watchmakers Vincent Bérard and Kari Voutilainen, after which he was appointed watch restorer at the Musée international d’horlogerie (MIH) in 2013.

‘Restore, but don’t improve’

An important guiding principle for Kanazawa is the motto, “restore, but don’t improve”. The focus of the work is on restoring the original function so that the timepiece can be passed on to the next generation without any problems, he explains.

“It would be strange if a watch from the 17th or 18th century worked like a modern watch. If the watch is in a terrible condition, it must be restored such that its condition does not deteriorate any further.”

This has sometimes been frustrating for him. “A badly made watch will still be badly made after 200 years. I have always been a bit annoyed seeing watches like that. I thought I could have made them better if I had used modern technology,” he says.

As a rule, he doesn’t restore a watch back to mint condition, he says. “It would also be strange if a 90-year-old grandmother looked 40 years younger after treatment in hospital,” he points out. He sees himself more as a “watch doctor” than a cosmetic surgeon.

But there are grey areas. For example, a watch that was worn by a soldier in a war cannot be left in a dirty, rusty condition – but you can’t make it look like new, either. “Every scratch has its own story. This is where the skills of the restorer come into play,” he says.

Professional secrets lost to time

Another challenge for restoration work is that the watch industry has traditionally been very secretive, and there are some techniques that watchmakers have taken to their graves instead of passing them on to the next generation. “If there is no information available for restoration, the only option is to look closely at the watch and try to decipher it,” Kanazawa explains.

When it comes to rare but not unique watches, he sometimes contacts other workshops that have restored similar watches. This not only expands his knowledge, but also allows him to take a systematic approach to things, says the restorer.

“Especially when it comes to decorative aspects, you can’t always recognise the original just by looking at the model,” he says.

“By gathering information on similar pieces, we can carry out restoration work that not only matches the function, but also the style of the maker.”

Originally, Kanazawa wanted to return to Japan after a few years in Switzerland to open his own establishment. It has now been more than two decades, and there is no sign of him returning to Japan any time soon.

In La Chaux-de-Fonds, in the north-west of Switzerland, many buildings are four or five storeys high and face south. This is to make the most of sunlight to provide optimum working conditions for the watchmakers, who must perform a lot of delicate tasks.

After being destroyed by a major fire in 1794, La Chaux-de-Fonds was rebuilt around the watchmaking industry that had existed since the 17th century. In 2009, La Chaux-de-Fonds, together with the neighbouring town of Le Locle, was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage Site List for its ‘watchmaking town planning’.

Edited by Reto Gysi von Wartburg

Translated from German by Katherine Price/ac

More

Business stories by SWI swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.