Rolex: how the queen of the watch industry keeps its secrets

How did Rolex conquer the world? It was all primarily down to skilful marketing, says a new book. The author, Swiss historian Pierre-Yves Donzé, says his task of charting this success story was not made any easier by the company’s traditionally tight-lipped policy on its own inner workings.

In 1977, in the middle of a crisis in the watchmaking industry, Rolex bought a building in downtown New York for $15 million (CHF13.7 million). As competitors like Longines and Omega struggled, Rolex held fast to its vision of the future.

In fact, the brand emerged almost unscathed from that crisis. Its survival was due to the Oyster, the legendary automatic watch model on which the Rolex saga was built. This timepiece served to anchor the company in stormy weather. Other producers fared poorly because their ranges were not suited to mass production.

Rolex was also very skilful at launching advertising campaigns that associated the product with personal success. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the economic upturn in those years and the popularity of rags-to-riches stories, this approach found a ready reception. The brand’s path to victory had begun.

Operating outside the time dimension

The Rolex phenomenon aroused the curiosity of Swiss historian Pierre-Yves Donzé. He wanted to know just what it was that helped the company put its competitors in the shade. He is a professor of economic history at the University of Osaka in Japan. His field of specialisation is the watch industry.

The problem right from the start for Donzé was the secretive attitude of Rolex itself. The company keeps its archives closed to outsiders, including researchers. It’s not listed on the stock exchange and it never communicates about its own history. There is no company museum or official accounts of its history. It does not even celebrate anniversaries.

Thus the historian writes in his book, La fabrique de l’excellence (The Factory of Excellence): “Rolex has no history, for the brand itself is timeless. It operates outside the time dimension entirely and exists as a myth with a quasi-religious halo around it.”

Donzé began his research in 2019. Rolex provided him no access to its history, but that did not stop his inquiries. On the contrary, he likes to compare his research to finding out about medieval history. “Sometimes there is only a manuscript or two you can refer to,” he says.

Given this situation, Donzé had to resort to secondary sources. These included old company registers and documents from industry associations or trade unions. He had to dig deep into the archives of companies and cantonal and federal authorities. Getting to these sources took a lot of time and travel. Donzé finds a positive aspect to all of this detailed work. “The process lets things mature,” he says.

History based on a founding myth

The history of Rolex, as told by marketing managers and reproduced by collectors in articles and blogs, is based on a founding myth: it all began with the genius of an entrepreneur who was also an extraordinary inventor. Company founder Hans Wilsdorf (1881–1960) was orphaned at the age of 12 and as a young man sold watches in England. He dreamed of designing a waterproof watch.

The years between the wars were decisive for the acceptance of wrist watches. Unlike traditional pocket watches, these new timepieces were subject to mechanical strain, moisture and dust.

In 1926, Wilsdorf developed the Oyster. It’s an incredible story, but one so brief it seems too good to be true. Donzé too sees it this way. He argues that the idea of a waterproof watch had already been around for decades

The Oyster was also just one model among many, for Rolex had not decided on a particular product. “They later turned Hans Wilsdorf into a kind of Steve Jobs,” says Donzé. The future watch company owner was portrayed as a lone genius who one day stood up and declared: “I’m going to make a waterproof automatic watch.”

In reality, technical advances are always the result of a collective effort, says the author.

The great watch brand used several suppliers in its pioneering days. Rolex also bought up several patents for waterproof cases in the Jura mountain region of western Switzerland. From the outset, advertising played a significant role. “The rise of the Rolex brand is an example of how innovation can develop in the right industrial environment with opportunities for entrepreneurship. This is not about genius emerging out of nowhere,” Donzé points out.

In fact, until the 1950s, Rolex was a mid-sized company that followed the same strategies as its competitors to carve out a place for itself in the Swiss watch industry. The firm focussed primarily on quality and precision.

Saga takes on legendary dimensions

The Rolex saga only took on legendary dimensions in the 1960s under André Heiniger, the successor of Hans Wilsdorf at the helm of the company. He used the services of American advertising agency J. Walter Thompson (JWT). “This was an important link between Geneva and New York,” says Donzé.

Without doubt, Rolex has always produced outstanding watches. But that in itself is not enough to achieve the cachet of excellence. Just like Omega, Longines and Zenith, Rolex took part in chronometry competitions. All these manufacturers were competing to produce the most accurate wrist watch. But this qualification alone could not turn a company into a legend. It was the masterfully orchestrated communication of the JWT agency that brought Rolex closer to the status of icon.

More

Rolex breaks taboo with takeover of Bucherer

Since the 1950s, the identity of the Swiss luxury brand has depended on a three-pronged message: extraordinary watches, created by an extraordinary man for extraordinary people.

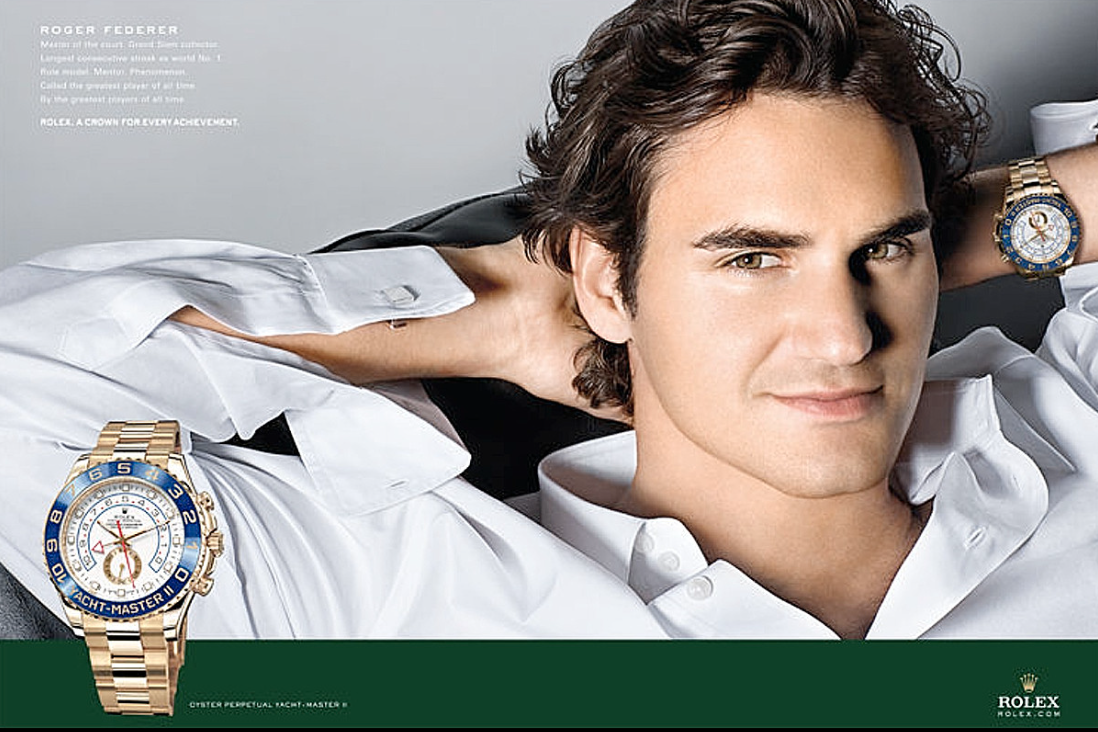

Rolex watches now glinted on the wrists of prominent politicians, athletes and business-people – the heroes of their time. “The brand basically represents masculine values. It reflects the self-perception of the white man of the upper-middle class in the years of economic growth,” Donzé writes in his book.

No need for innovation when you’re number one

Rolex had found the magic recipe for success. The brand no longer needed to be innovative. Why would it be? It maintained its existing collections and elevated them to iconic status.

Rolex has stayed one step ahead of its customer base and the competition. It could be sure of its place in the sun for years to come. Other manufacturers have fought it for a piece of the cake. They had a go at mass-producing quartz watches. The Swatch struck a chord with buyers. Others have successfully revived once-famous brands. But Rolex just stayed the course as the undisputed number one in the industry.

“To be able to say that you no longer need innovation, because you have found the philosopher’s stone, doesn’t come without some amount of cheek,” says the historian.

Rolex, the inscrutable label, has not always kept a low profile, adds Donzé. Fifty years ago, no one was interested in corporate history. It was only in the 1980s and 1990s that companies began to look into their own past. This resulted in the first corporate collections and museums – but not at Rolex.

‘The hero of the story is always Rolex’

Donzé is all too aware of how historical research can take the air of enchantment out from a story. This is true of the Rolex empire. “Anyone studying a success story brings to light processes that can demystify a myth,” he writes.

His four-year research project changed his own view of Rolex. “Now I have a better understanding of what seems thoroughly inscrutable to outsiders,” he says, adding the company is “a very instructive case study for a business-school seminar”.

He is impressed by the way successive company bosses were content to stand in the shadow of the brand itself, obeying the maxim that “the hero of the story is always Rolex.” Previous books on the company have been too much like watch catalogues, says Donzé. The people and their work behind the scenes got little attention.

Donzé would like to lift the veil even more, because Rolex is “not just an industrial empire but a financial one”. This dimension is not open to study. The company is said to have considerable investments in real estate, banking and finance. “They may be making more from this than from the watches themselves,” says Donzé.

What happens at Rolex stays at Rolex

Donzé’s book also has a chapter on the dark days of the war. In 1941 the British government suspected founder Wilsdorf of collaborating with the Nazis. An investigation by the canton of Geneva came to the conclusion that Wilsdorf was “an ardent admirer of Hitler’s regime”.

“This discovery was a surprise to me,” says Donzé. He would have liked to know more about it, but found no documents in the Geneva police archives covering this period. This tranche of files seems not to have been retained. There may have been just too many prominent people in Geneva who had contacts with the Nazi regime and Vichy France.

The brand image of Rolex remained unscathed despite Wilsdorf’s ties. But there were economic consequences for the boss himself: the British government would not allow him to export his watches to Britain.

Today about 3,000 people work at the Rolex factory in Biel, a city in western Switzerland. If Rolex itself tends to be uncommunicative, its staff are the same. “The company offers great working conditions. It would be foolish for employees to reveal company secrets with a careless statement,” says Donzé.

Those who join the staff of Rolex tend to stay with the company their whole working lives. They are proud to work there. Trade union sources confirm that in the company’s history there have been only two labour conflicts – in the years 1916-1922 and during the 1930s.

This article first appeared in the newspaper Bieler TagblattExternal link and is reproduced here with permission.

Adapted from German by Terence MacNamee/gw

Did you like this article and would you like to receive our best content directly in your mailbox? Subscribe to our newsletter.

More

Can Swiss watchmakers survive another century of disruption?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.