A candle on the coronavirus cake

From January 2020 until today, the world has been in the grips of to a tiny organism, invisible to the naked eye. Raise your hand if you could imagine a year ago how much our lives would change.

About a year ago, on January 20, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the new coronavirus to be “a public health emergency of international concern”External link. At the time, there were less than ten thousand cases worldwide and no deaths outside China. A year later, we are still in the midst of a global pandemic that has taken the lives of more than two million people and infected more than 100 million. The figures certainly do not compare with the terrible Spanish fluExternal link of the early 20th century, which has been dug up over the past year from the dusty drawers of history to remind us that history often repeats itself. At the beginning of the health emergency, well after 30 January, many politicians and experts had underestimated SARS-CoV-2, branding it as a “simple” flu or even a “measly cold”External link . The thinly veiled message was that there was nothing to worry about. Can “a flu” send the world into a tailspin in the 21st century? A year ago it was not thought possible. Now the answer would be a clear “yes”.

My colleague Marc-André Miserez looked back on his experience as a journalist in the midst of a health crisis, recalling how the initial certainties of a year ago have crumbled in the face of the reality of the galloping epidemic. Here’s Marc-André, and the questions I put to him about this moment of self-reflection.

“Is the world right to be afraid of the Wuhan coronavirus?”. By asking the question in early February 2020 – without even saying so – I was sure I had the answer. Arrogance! I should have remembered that you can never be sure of anything.

Marc André, as a journalist, how did you experience those first weeks of February, when the fear of the virus was beginning to mount?

At the time, no cases had yet been registered in Switzerland – the first one will be declared on 25 February – but there were already concerns. In medical circles, as well as in newsrooms.

At swissinfo.ch we were in the midst of the debate. Convey fears to readers? Or rather reassure? Should we wait and see what happens? We are journalists. Our duty is to inform. With a certain bravado, I volunteered to see if I could write something about it.

What did you do then?

I contacted an epidemiologist, who told me honestly what he knew. Which is to say, not much. The new virus was easily transmitted, but its mortality rate was estimated at around 4% – today it’s more like 2%. According to the WHO, the mortality rate was 9.5% for SARS in 2003/2004 and 34% for MERS in 2012. Both of these global coronavirus epidemics caused the death of less than a thousand people each. That is between 300 and 600 times less than influenza, which returns every year.

And these figures reassured you…

Yes, the comparison was reassuring. All the more so because the mortality rate is always lower than the statistics suggest, because there are usually far fewer declared cases than actual ones… But I should have remembered that the comparison is misleading.

So you changed your mind?

Of course, today there is no doubt. Covid-19 is indeed a global scourge. And the comparison with the 50-100 million victims of the so-called Spanish flu of 1918-20 does not work: in a century, health systems have made significant progress globally. Moreover, never before has a virus caused so much damage to the economy and society, depriving millions of people of their livelihood, or even reason to live, as only wars can do.

To err is human, to persevere is diabolical. If you could go back, what would you say to your readers then and, perhaps, now?

I would tell them that yes, the world was right to fear the Wuhan coronavirus! And to the 140,000 or so people who read my article a year ago, I owe a humble apology: I was very wrong.

Personally, I don’t remember taking a clear position at the beginning of the epidemic. As an Italian transplanted abroad (I was living in Paris at the time), I was in a sort of limbo, between the paradox of the rapidly worsening Italian situation and the placid French indifference. In Paris, people began to realise very late that the situation was getting serious. By a strange coincidence, the days were mild and sunny in the City of Light and no one wanted to miss the opportunity for a picnic in Les Tuileries or a coup on the terrace of some café.

Of course, there were those who knew best and predicted the impending catastropheExternal link. The head of Moderna, Stéphane Bancel, had already realised in January that the virus was starting to travel everywhere. On 24 February, Moderna sent the first clinical samples of its vaccine to the US Department of Health.

And you? How did you experience the beginning of the pandemic? If you were to go back, would you do or laugh at the same things? Let’s talk about it! Write me your comments.

The virus wastes no time

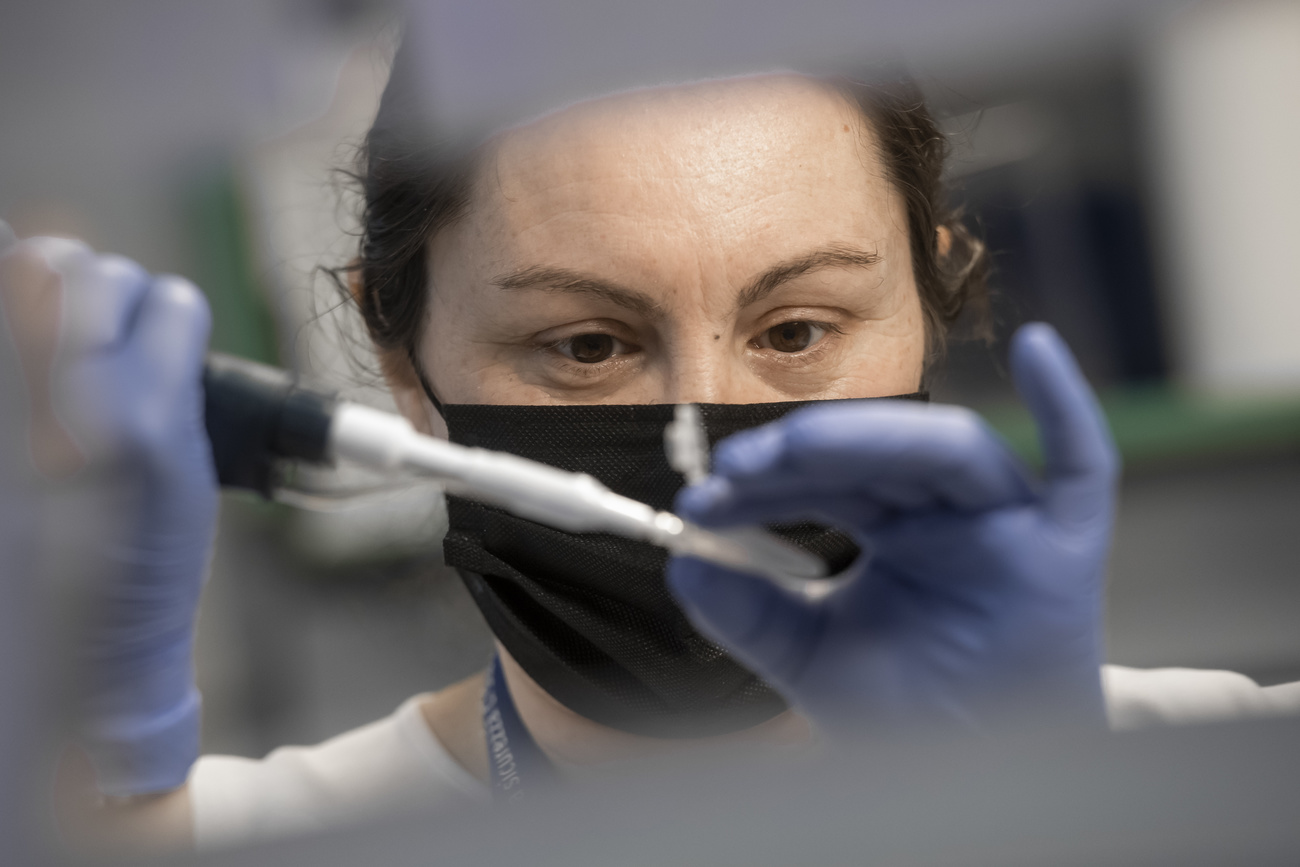

While the world agreed on the seriousness of the situation and the measures to be taken, the virus wasted no time. From one contagion to the next, it was modifying small parts of its genetic code to continue reproducing and infecting new (or even old) victims. Genomic epidemiologist Emma Hodcroft, who works at the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine in Bern, has been following the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, and tells us in an interview how the virus has mutated and become more and more contagious: from a scientific point of view, the evolution of the virus is completely normal. But every time the virus replicates, there is a chance that an error will occur, and that this will generate a mutation. The longer we play this game, with a high number of cases and a high concentration of the virus in circulation, the greater the chance that the next mutation will be one we don’t want to see. That’s why, according to Emma Hodcroft, it’s very important to keep infections low and not give the virus space.

More

‘The virus is always evolving’

British epidemiologist Adam Kucharski also confirmed in an article in the Financial TimesExternal link that an accumulation of mutations has the potential to dramatically change the face of the pandemic and the threat it faces. For the worse.

Vaccine race and digitisation

Vaccines could be a real game-changer in curbing the virus, but the vaccination campaign is proceeding slowly in Switzerland, due to delays in delivering doses. But this is not the case for everyone. Israel, similar to Switzerland in terms of population, is the first countryExternal link in terms of the number of vaccines administered per capita. Why? One of the determining factors is certainly the efficiency of its digitised healthcare systemExternal link. In Switzerland, however, the digitisation of healthcare is far from being a reality. And this could cost the population dearly. I will talk about this in a forthcoming article, which you’ll find on swissinfo.ch.

Stay tuned!

Do you have an opinion? Let’s talk about it over a (virtual) coffee.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!