The miracle of Picasso in Basel

The greatest artist of the 20th century, a grassroots hippie movement, super-rich chemical industrialists, direct democracy: all the ingredients of a fairy-tale story in which, 50 years ago, Basel voters said “yes” to the purchase of two Picassos.

The story has a magical ending but a dramatic beginning – with an aeroplane crash in torrential rain. In April 1967, a Globe Air plane smashed into the ground while landing in Cyprus. Some 117 passengers and nine crew members were killed, and the catastrophe prompted the small airline to slide into bankruptcy soon after.

The main shareholder of the company was forced to take on the bulk of the high liability payments. He was Peter G. Staechelin of Basel, whose family was known for its large collection of artistic treasures, including paintings by Van Gogh, Monet, Cézanne, Picasso, and Monet. The most important of these works hung in the Basel Kunstmuseum – assets on canvas that Staechelin now had to convert into cash.

‘Of great value to art history’

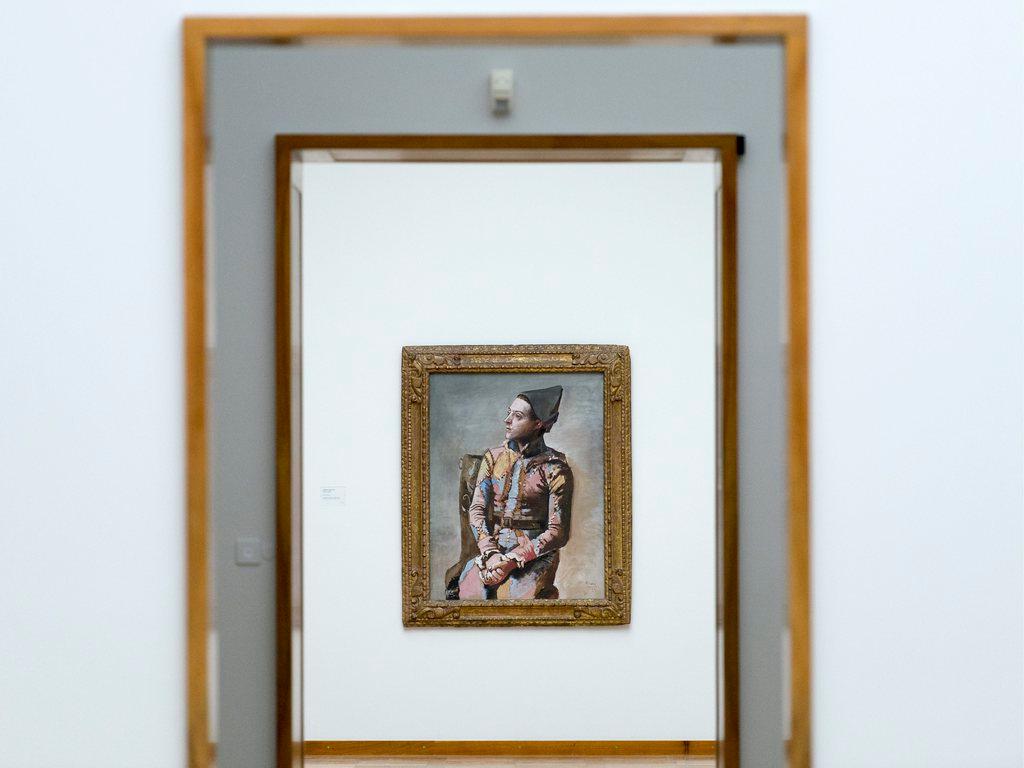

He first sold a Van Gogh for CHF3.2 million ($3.3 million). Then news trickled through that the next to go would be “Les deux frères” and “Arlequin assis” by Pablo Picasso.

“These pictures are of great value to art history,” said Eva Reifert, curator of 19th-century and classical modernist art at the Basel Kunstmuseum. “Les deux frères,” painted in 1905, and “Arlequin assis,” from 1923, mark the beginning and end of Picasso’s Cubism phase – a movement the Spanish artist founded. For Reifert, it was inconceivable that they could disappear from the museum’s collection.

So, before the paintings were auctioned to the highest bidder, the Kunstmuseum’s board hit the emergency brakes. It called a meeting with the Staechlin Foundation and the cantonal government, which resulted in a decision that would only have been possible in the art hub of Basel at that time: the foundation offered the city the two artworks for the price of CHF8.4 million.

The government was willing to pay CHF6 million from its own coffers; the remaining CHF2.4 million had to come from private donors. And, lo and behold, the cantonal parliament went along with the idea. The credit was approved with just four votes against.

A challenge is mounted

Local artists and citizens were generally caught up in a wave of euphoria. They set up a campaign to raise the missing amount of CHF2.4 million.

But one man was utterly disgusted at the enthusiasm for the two Picassos. Alfred Lauper, a garage owner, had lost a lot of money through the bankruptcy of Globe Air as a small shareholder, and saw no need for the public authorities to invest in high art. Lauper initiated a petition against the parliamentary decision and quickly gathered enough signatures for a referendum.

The people were divided. Kurt Wyss, a news photographer who is now 81 and who worked at the time for the Basler Nationalzeitung newspaper, remembers the rift that opened between old and young. “We young journalists were absolutely convinced that the city had to buy the paintings. Our older colleagues told us we were crazy. We could build two old people’s homes with that money.”

‘All you need is Pablo’

Readers’ letters filled columns of the newspaper. Advocates and opponents were finely balanced. Pasted across the city were slogans proclaiming “I like Pablo” and “All You Need Is Pablo”; a reference to the Beatles hit “All You Need Is Love,” which became the soundtrack for the hippie movement that same year.

The fiery debate on the Rhine spread across the rest of German-speaking Switzerland. The canton of St Gallen promised a donation, the neighbouring canton of Basel Country shelled out CHF80,000 without even being asked, even the Basel municipality of Binningen found CHF2,000 for the cause.

Once large donations from the local pharmaceutical industry and the super-rich upper classes of Basel came through, a total of CHF2.5 million was tallied – CHF100,000 more than necessary.

Whisky with Picasso

More

Facelifts for Swiss museums

But nothing was signed nor sealed. The colourful alliance awaited the looming referendum with trepidation. In the end, their fears were unfounded: on December 17, 1967, Basel voters approved the credit for the Picassos with a large majority. There was jubilation in the streets. Young people, artists, and many other citizens came out to celebrate.

“In the flush of victory, we suggested meeting Pablo Picasso for an interview in southern France,” recalls Kurt Wyss. The culture editor waved them aside. Picasso hadn’t agreed to give an interview for ten years. But Wyss and his colleague Bernhard Scherz flew that very day to southern France, where the artist, originally from Spain, had been living for several years. In their luggage, they carried documents chronicling the events in their city and a glowing letter of recommendation.

That same evening, Wyss and Scherz knocked on Picasso’s door and handed over their recommendation letter and some of their documents to a domestic employee. The next day, the two men were walking again to the home of the artist when a giant limousine approached from the opposite direction. A window slid down and Jacqueline Picasso (Pablo Picasso’s wife) looked out.

“Are you the gentlemen from Basel?” she asked. “Come around 5 p.m. There’s a big surprise waiting for you.”

How one picture became two

The two journalists arrived long before the appointed time and were brought into Picasso’s studio. There they found not the artist, but a man whose jaw dropped when he saw the visitors: it was Franz Meyer, the director of the Basel Kunstmuseum. Meyer announced proudly that Picasso had promised him a new painting, a present for Basel. He could choose one then and there.

“Meyer was cunning,” says Kurt Wyss. “He took a long time deliberating over two paintings, saying that they somehow belonged together. Jacqueline Picasso agreed.” In the end, Picasso gave both paintings to Basel. And there was more. The artist had already decided to donate a 1906 painting from his Rose Period to the Kunstmuseum. And to add to the trove, he even presented a sketch for “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” – an iconic piece of art history that ushered in the Cubist movement.

The spontaneous and generous reaction showed just how moved the 86-year-old Picasso was by the Basel referendum. “He was on top form,” says Wyss. After Meyer had snared his two paintings, Picasso led them into the salon because he wanted some tea. “But he gave us whisky,” says Wyss. The men chatted. “It was wonderful.”

A gift for the young people of Basel

When the subject of the pictures came up in conversation, Picasso said: “I am not giving these pictures to the public official” (meaning Franz Meyer). “I am giving them to the young people of Basel.” And with these words, he put his arms around the young journalists. “That was a very moving moment,” Wyss says, adding with a sparkle in his eye: “I haven’t washed since.”

The Picasso miracle of Basel was not just a victory for art. It was also an advertisement for direct democracy, something made clear by later reporting in big international publications like the New York Times and the German magazine Der Spiegel.

Leonhard Burckhardt, a Social Democratic member of the Basel cantonal parliament and a professor of history at Basel University, was 14 at the time. “This event was a milestone for me and for many of my generation,” he says. “We experienced in a very immediate way how a referendum can function as a cornerstone of democracy.”

Burckhardt has no clear answer as to whether something similar would be possible today. “That is pure speculation. But the fact is that even today a large part of the population of Basel can identify with the Kunstmuseum. And the people here still love art.”

The Kunstmuseum is celebrating the 50th anniversary of this success in appropriate style. From January 2018, the museum is holding a special exhibition to commemorate the unusual circumstances that made this “Basel miracle” possible.

Translated from German

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.