Climbing the Matterhorn

On the way to the summit of Switzerland’s iconic Matterhorn, the site where the rope broke in one of mountaineering’s most famous accidents is quickly followed by an eerie statue of St Bernard, patron saint of alpinists. It’s a reminder that climbing the peak is more than a physical challenge; a climber also has to grapple with history and myth.

Earlier this year I became a swissinfo.ch reporter in Bern and soon after was given the assignment to write about the 150th anniversary of the Matterhorn’s first ascent and to hopefully climb it, too. I jumped at the chance.

The assignment became a personal journey, combining my family past, climbing and work experience. It provided an opportunity to peel back the layers of image-making and get to know the 4,478-metre peak itself. It also helped rekindle an essential part of myself that had been constrained for too long.

More

The legacy of the Matterhorn

External linkGrowing up in the United States, summers were for hiking in the mountains. Then came rock climbing and mountaineering, and my ambitions grew. My mother’s most treasured photo frame from her youth held three of family and one she took of the Matterhorn. My father, who spent part of his childhood in Switzerland, introduced me to one of his favourite books, “Banner in the Sky”External link, by James Ramsey Ullman.

It’s a fictional account of a boy who grows up to be a mountain guide in a village just like Zermatt and helps make the first ascent of a mountain (just like the Matterhorn) that killed his father. It wasn’t just my favourite book; I wanted to be that boy, Rudi Matt. A film version was shot in Zermatt in 1958.

Looking up

For several years I worked as a mountaineering and backcountry skiing instructor. Over the decades I climbed at Chamonix, Nepal’s Everest region, the North Ridge of K2 and Denali in Alaska. I went on honeymoon in Zermatt. I joined the board of directors of the American Alpine ClubExternal link. But when I moved to Bern in 2010 with my Swiss wife and two young Swiss-American boys, I had a job in Geneva that kept me from getting out much.

The assignment meant getting to know direct descendants of the father-son Zermatt mountain guides Peter Taugwalder Snr. and Jnr., who, along with British climber Edward Whymper, led and survived the first ascent.

For training and reporting, I went up the Riffelhorn, Wiwannihorn and Rimpfischhorn with Zermatt mountain guide Gianni MazzoneExternal link and his cousin, photographer Matthias TaugwalderExternal link. I wasn’t used to being guided but I immediately liked Gianni. A good thing, too, as he would be my guide on the Matterhorn.

We set off on July 12, on what turned out to be an unusually perfect day for it. A very experienced guide, Mazzone knows the route inside out and has led hundreds of people up it including even Miss Switzerland of 2009.

Below us the village was overrun with hordes of snap-happy tourists, there for the July 14 festivities to mark the first ascent. Countless merchandise reflected the mountain, village and Alpine nation.

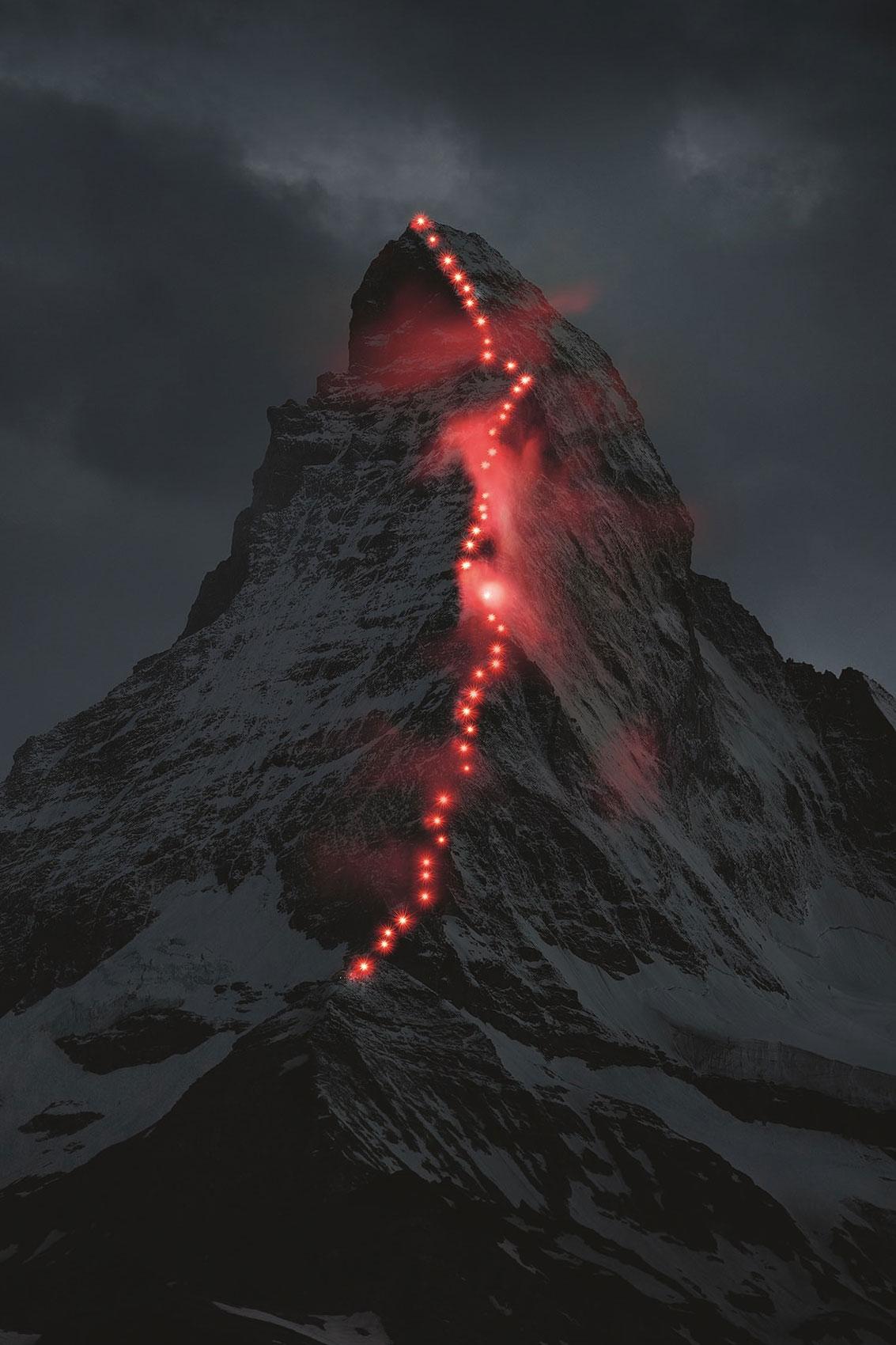

The classic route up the Hörnli ridge offers a dizzying view straight down the north face where three English climbers and a French guide plunged to their deaths during the first ascent, as this interactive image from Matthias Taugwalder shows.

Its popularity gives rise to a mistaken notion that it is safe and easy, the same way people think anyone with $65,000 (CHF62,000) to spare can climb Mount Everest these days.

Experience, fitness and always the weather come into play. Intricate route finding and the long, technical descent also help explain why some 500 people have been killed on the Swiss side alone, according to figures from Zermatt’s tourism office. About 3,000 try it every year.

Forgetting the myth

Hiking up to the newly renovated Hörnli hut – which reopened in July after a two-year construction projection costing CHF8 million ($8.4 million) – my head was still spinning with details about the triumph and catastrophe of the first ascent. It scarred families, sparked an international media frenzy that fuelled a fledgling sport and transformed Zermatt into a world renowned tourist destination.

The mountain’s stunning architecture provided a shot of adrenaline from any vantage point. It was easy to imagine how people in the 1800s could view it as possibly unclimbable. But as I got closer, and higher up, the cultural images gave way to the sheer enjoyment of an elegant natural wonder. Then I stared up at it the evening before, wondering if I was really going to make it up.

There were unusually few climbers or guides at the hut and on the mountain, owing to the upcoming anniversary when the mountain was closed to honour the past. Gianni went over my equipment carefully, helping me pack. The hut was thoroughly modern, with charging outlets for the ubiquitous smartphones. The food was delicious.

The ascent

I had trouble getting to sleep, tossing and turning most of the night.

After about an hour’s sleep, I got up at 3:20am and joined Gianni for a quick breakfast. I worried I might be too tired. Partly owing to his seniority as a guide, Gianni and I were first in line to get on the route. We climbed with headlamps attached to our helmets.

The darkness was a comfort because it obscured the growing void below me, helping me focus only on following Gianni’s boot heels. “Slowly and surely. Left foot here. Right hand there”, Gianni would say, part of his constant stream of guidance. “Always look to your feet and to the rhythm.”

Within a couple hours we reached the Solvay refuge, a tiny emergency hut at 4,000 metres, two-thirds of the way up the route. Our time was fast. I began to think I was really going to pull this off after all. The climbing felt great. I was loving it. Higher up, we attached our crampons to navigate the ice, snow and rock.

Until we reached the narrow summit ridge, I had been thinking that would be the scariest part. I’d watched GoPro videos and worried about having to walk the equivalent of a balance beam of rock and snow above a drop of thousands of metres on both sides. But by then I’d gotten my groove back. I had my own GoPro helmet camera, first time for me, and I had been more or less precisely following Gianni’s boot heels for hours. He also had me on a tight leash of rope.

We were first to reach the summit that day. We got there in 3 hours 45 minutes and had the summit to ourselves for at least a quarter hour. That was unusual, and made it all the more special. Gianni dedicated his 287th summit to his ancestors who made the first ascent.

More

Reaching the summit

The big surprise was going down. It was by far the most difficult part. Gianni had me climbing down “monkey style”, which requires facing outward with one hand on the rock and leaning into the fall line, like a skier must do on a steep slope. It’s hard on the leg muscles, and, after a few hours, mine were burning. With the altitude and dehydration, I felt a little dizzy at times. The last hour was gruelling. I dug deep.

There were a couple of moments when I felt a little bit off-balance. Instantaneously, I felt a tug behind me. It was hard to admit it to myself, but in those moments I knew I needed a guide like Gianni. He kept asking me how I was doing, and I kept telling him I was fine. Nearly all the time I meant it; just a few times I think he knew I was reassuring myself.

By 12:30pm we were back at the Hörnli hut, and his wife and son were waiting for us. I had to drink several ice teas and soup to recover. Then it was time to head back down to the valley. I felt incredibly happy, and relieved. I had completed my assignment. And now I had my own sense of the Matterhorn.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.