Dentists: a luxury for more and more Swiss people

A growing number of people in Switzerland are forgoing dental treatment for financial reasons. Some are turning to trainee dentists to take advantage of discounts. Opinions are divided on the best solution to the broader problem.

“I’ve always avoided the dentist,” says Frédéric*. At the beginning of 2022, however, the 63-year-old pensioner from Geneva had to face the consequences of his “terror of the dentist”.

“My teeth started falling out like autumn leaves,” he says. This time, Frédéric had no choice but to urgently consult a specialist. And the diagnosis was unequivocal: he would have to wear a dental prosthesis.

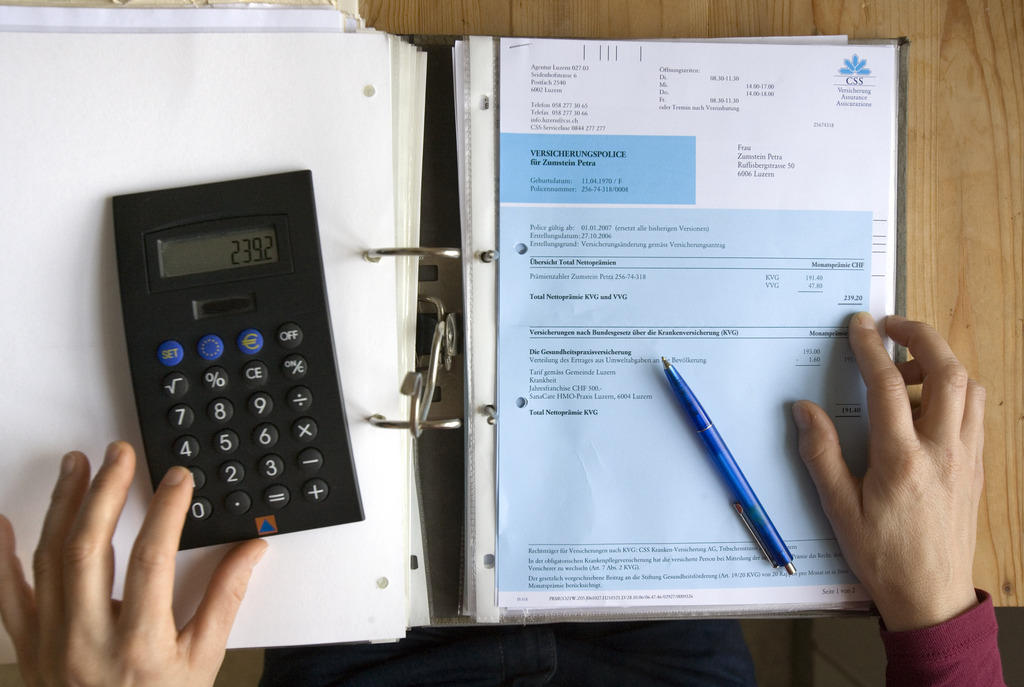

The bill is huge. This type of treatment can cost around CHF10,000 ($11,070), given that the cost of treating one cavity in Switzerland is around CHF1,000. What’s more, dental expenses are not reimbursed by compulsory basic health insurance.

Frédéric couldn’t afford the cost. So he started looking for other solutions. “At first, I thought of going abroad for treatment, but I thought that was too risky in case of complications,” he says.

So he opted for treatment at the dental clinic of the University of Geneva. This institution, which trains the dentists of tomorrow, offers its patients a 70% discount on treatments carried out by students under the supervision of a qualified dentist. “To cover the remainder of the costs, I was helped by a foundation that assists people in need from time to time,” Frédéric says.

He was satisfied with how this worked out – he was able to benefit from high-quality care at a preferential price, while contributing to the training. “Each treatment was carried out by a student overseen by a supervisor,” he says. “Thanks to this double supervision, I felt even safer than in a standard dental practice.”

More people forgoing treatment

While Frédéric has found a way to get dental care, many others are giving up on having their teeth professionally looked after. These people are not on welfare – social security recipients have their dental costs covered by the state – but their income is insufficient to pay for dental treatment.

Estimates for the number affected vary considerably, depending on the indicators used in existing studies. In 2020, 2.4% of the population had to forgo necessary dental care due to a lack of financial resources, according to a survey by the federal statistics office, which notes that this proportion has remained stable since 2015.

The International Health Policy Survey, a study carried out by the Commonwealth Fund, an American foundation, arrives at a much higher figure based on a broader definition. It estimates that in 2020, 26.4% of the population opted out of dental treatment or a check-up (not necessarily essential) for cost reasons. This figure has risen by 5.7 percentage points in four years. In an international comparison, the number of people who go without treatment is higher in Switzerland than in France (18.5%) or Germany, but lower than in the United States (36.2%).

Teaching comes first

“We don’t have a social mandate,” say Chiara di Antonio, the administrator at the University of Geneva dental clinic, and Serge Borgis, director of operations. “Our primary goal is to have enough patients to meet our teaching needs.” Each year the clinic sees about 10,000 patients – some of them receive treatment from the 60 or so undergraduates.

“Each student treats several dozen people during their course,” Borgis says.

In 2022, the clinic changed its pricing system to attract more patients. Previously, discounts of 25% were offered for all treatments without prostheses, and 40% for prosthetic treatments. They are now set according to the level of training: 70% for treatments carried out by undergraduates and 25% for treatments by dentists in specialised training.

“These preferential rates have enabled us to attract patients who are prepared to go further in their treatment,” says Borgis.

On the consultation floor, more than 90 glass-fronted rooms are available to future dentists. The adjoining corridors are bustling with activity. Supervisors and assistants move from one practice to another to check on the work.

In the room where fourth-year student Hanza Shabana is working, concentration reigns. Only the sound of dental instruments in use breaks the silence. The young man is treating José Haeberli, who is also a pensioner from Geneva. The student is performing an onlay, which involves preparing a tooth before fitting a prosthesis.

Treatment at the university clinic can take three to four times longer than in a private dental practice. It begins with a scheduling consultation with a professional dentist, to assess needs and define a treatment plan. Haeberli, who has already been treated by several trainee dentists, values this process: “As I’m retired, I have plenty of time, and the discount means I can go further with the treatment”.

“We have all kinds of patient profiles, but the discount isn’t the only motivation,” Di Antonio says. “Some people are happy to be able to contribute to the training of dentists, while at the same time benefiting from top-quality care.” Over the course of the treatment, Di Antonio observes a bond developing between student and patient.

Focus on prevention

In the clinic’s Social Action Unit, the atmosphere is different. Two handcuffed prisoners accompanied by a police officer are waiting for their appointment. The unit’s main task is to treat welfare recipients, but it also treats prisoners. Here, it’s not students who provide the care, but experienced dentists.

For these people, basic dental care is covered by the state, provided that it is necessary, simple, economical and appropriate. These constraints do not make prisoners good candidates for teaching. “We’re talking about basic dentistry, whereas we’re required to teach ideal medical procedures under the best possible conditions,” says Borgis.

This is also why Borgis opposes the inclusion of dental care in basic health insurance. “It would reduce the quality of dentistry, because we would have to opt for the most economical solutions, as we have to do with people on social welfare,” he says. He draws a comparison with the situation in France. “Although dental costs are reimbursed by the social security system, the quality suffers,” he says. “So people who can afford it turn to private practices”.

So how can people who are forced to forgo dental treatment get the help they need? Borgis is banking on prevention, which he says should be improved.

“Oral hygiene needs to be taught at a very early age,” he says. “With a minimum of effort, you can eliminate 80% of dental problems.” This view is shared not only by the Swiss Dental Association, but also by a majority of the Swiss people. Referendums on introducing a cantonal dental insurance plan have already been held in the French-speaking cantons of Vaud, Neuchâtel and Geneva, but so far these proposals have all been rejected.

Dental vouchers instead of insurance

Baptiste Hurni, a Social Democrat member of parliament and the president of the Swiss Patients’ Federation, believes that including dental care under basic health insurance would be the best way of guaranteeing access to dental care for all. However, he admits that this idea currently has no chance of gaining a political or popular majority.

“A campaign on this issue would be a disaster,” he says. “Basic insurance premiums are already too expensive and everyone would be afraid of having to pay even more.”

Hurni believes that the dentists’ arguments against compulsory insurance do not hold water. “Good dental hygiene is not enough to avoid all problems,” he says, pointing out that dental health has an influence on people’s overall health. In his view, dentists are primarily worried that a national fee structure would be introduced, similar to the current fee structure for outpatient medical services.

“The profession does not want costs to be controlled by the state, which would put pressure on prices,” says Hurni.

An alternative solution is emerging in Geneva. The cantonal chapter of the Social Democrats has tabled an initiative that would distribute dental vouchers worth CHF300 to people on low incomes. “This proposal may have a better chance of getting passed and could be emulated elsewhere in Switzerland,” says Hurni.

*name known to the editors

Translated from the French by Catherine Hickley/gw.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.