Exclusive guiding scene guards a celebrated brand

Zermatt’s proud and closely guarded mountain guiding culture reflects the character of the challenging peaks that have drawn adventurous tourists to the valley since the second half of the 19th century.

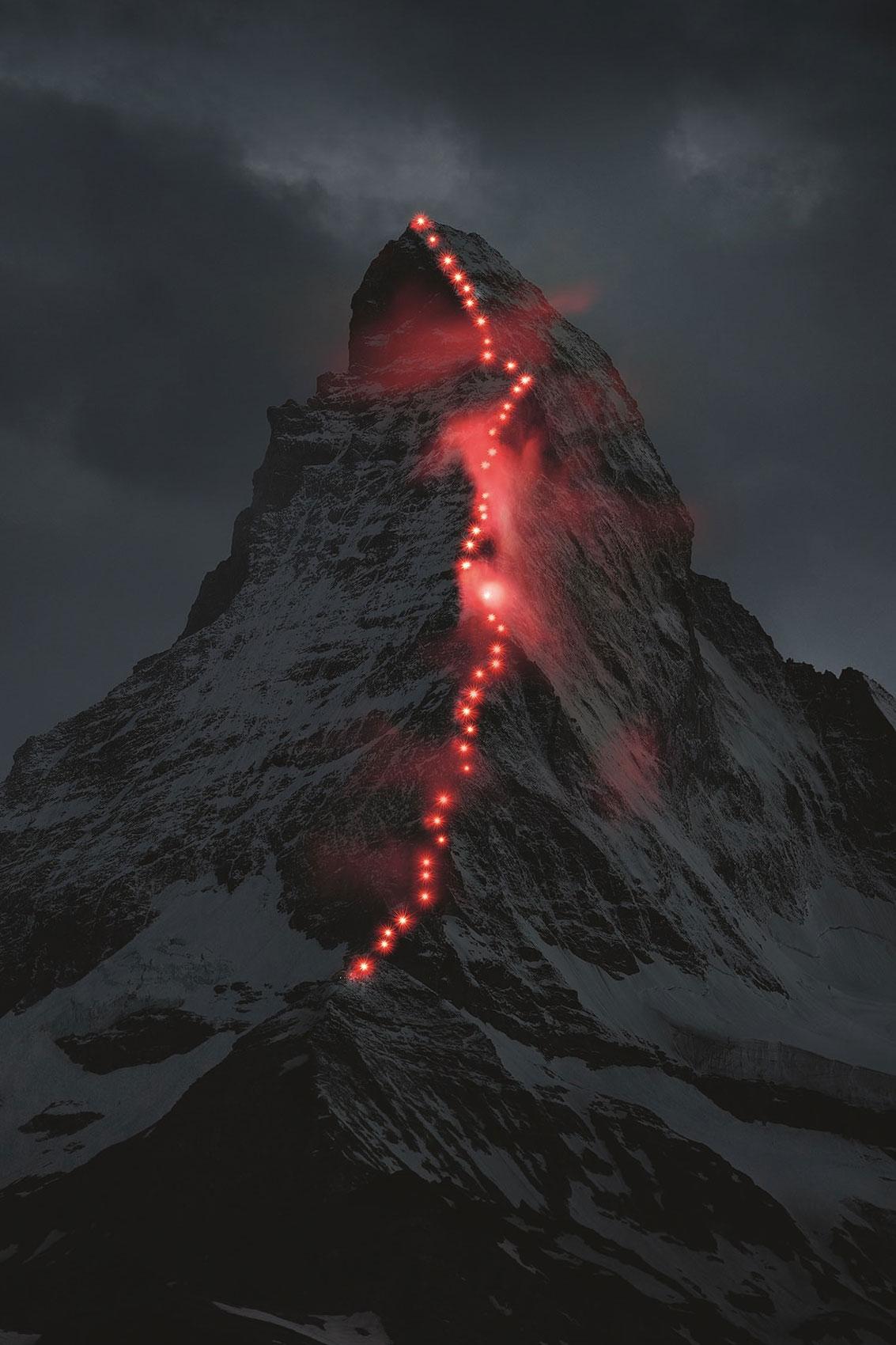

Few mountains achieve the architectural perfection of the MatterhornExternal link, jutting high above Zermatt like a surreal dinosaur’s tooth.

Its iconic shape and dozens of other 4,000-metre peaks in the area are a powerful attraction that helps sustain Zermatt’s tight-knit community of community guides. A local guild-like operation, it has fewer than 100 active members and is famously difficult for outsiders to crack.

More

The legacy of the Matterhorn

External linkAsk some of the most renowned Swiss climbers and they’ll tell you the Matterhorn has an archetypal beauty that makes it simply irresistible. The local guiding guild profits from the many who want to ascend to the summit each year. “When you see the mountain, you want to go to the top,” says Roger SchäliExternal link, a professional alpinist and guide who has put up new lines around the globe.

Not wanted: outsiders

Schäli – who is not from Zermatt – believes it’s a tough place for outsiders to work in. “If you are not part of the Zermatt family, than it gets pretty hard,” he says. He calls the Zermatt guides “superheroes at home” because they are revered on their own turf and know climbs like the Matterhorn inside out, which is extremely important to ensure their clients’ safety.

Over the years some 500 people have died on the Swiss side; another 200 on the Italian side. But Schäli says there aren’t many accidents with mountain guides on the Matterhorn; more often they occur among unguided climbing parties.

“The Zermatt guiding culture has a long and storied and magnificent history, but it’s also a very insular place and it’s a difficult place for anyone who’s not a Zermatt guide to guide. And they’re very protective. It’s healthy in some ways because they have this resource they care for deeply,” says Matt CulbersonExternal link, a US educator and veteran mountain guide on four continents who has served as president of the American Mountain Guides Association.

Cash cow

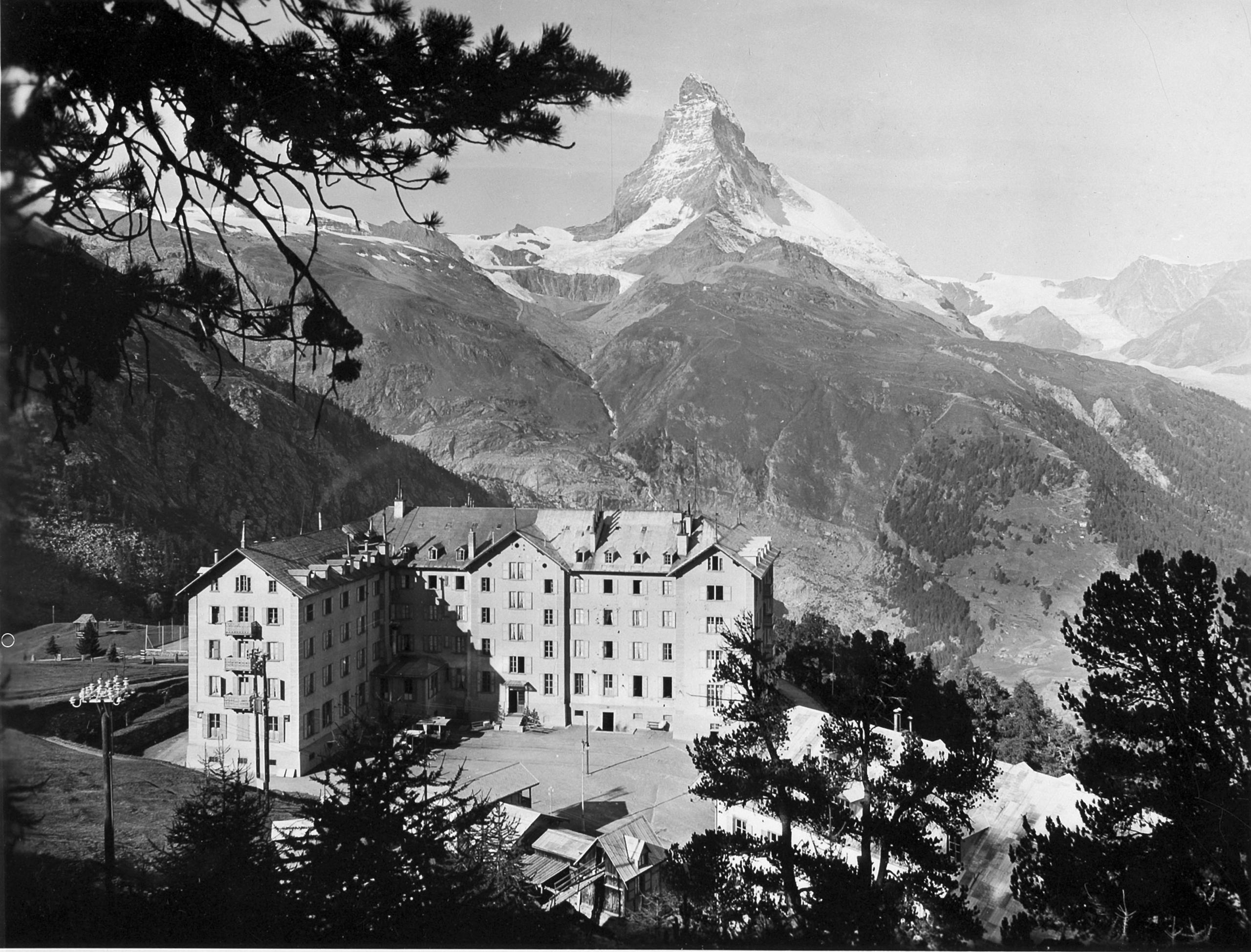

Swiss farmers had already begun cashing in on the Alps as a growing tourist attraction for climbers and walkers before the father-son Zermatt mountain guides Peter Taugwalder Snr. and Jnr. and British alpinist Edward WhymperExternal link became the sole survivors of the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865.

Before the first ascent, it was widely thought that the Matterhorn might be unclimbable or the abode of evil spirits, and some among the Zermatt mountain guiding community scrupulously avoided it. Not all.

More

150 years on, Matterhorn guides’ family stake claim in history

A few adventurous souls, like Taugwalder Snr., a Swiss farmer and mountain guide, saw the possibility of climbing the iconic peak straddling the Swiss-Italian border. Increasingly, it became a highly coveted prize in the golden age of mountaineering. The elder Taugwalder pushed the route up the Hörnli Ridge from the Swiss side that is now the modern-day classic.

Enter Edward

Jean-Antoine Carrel, an Italian stone mason and mountain guide, worked it from the Italian side. Neither succeeded until British enthusiasts like Whymper and John Tyndall entered the picture with the financial and logistical support of the Alpine Club of LondonExternal link, the world’s first mountaineering club.

Whymper’s triumph overshadowed Carrel, who led the second ascent three days later. The die was cast for mountaineering to be viewed as glorious and morbidly fascinating. The tragedy during Whymper’s descent led Queen Victoria to consider a ban on climbing for all British citizens. From a crass public relations standpoint, however, their epic climb provided a perfect storm of sensational controversy that put the Matter Valley and its upper village of Zermatt on the global map.

It was an adventure story with all the elements of a thriller: triumph and tragedy; passion and betrayal; and national ambition versus international cooperation. Measured by overnight hotel stays, the mountain village of Zermatt now comes in third in all of Switzerland behind only the much-bigger international cities of Zurich and Geneva, both centres for finance and business.

Edith Zweifel of Zermatt TourismExternal link notes that the first ascent of the Matterhorn helped popularise the sport of mountaineering in the Swiss Alps, and since then Zermatt and the Matterhorn, which now draws 3,000 climbers every summer, have become global brands.

Guiding lights

The Swiss mountain guiding industry took off, as part of the boom in summer and winter tourism. But Whymper’s accounts of the climb deeply scarred the mountain guiding community. “Still alpinism is the main thing for Zermatt,” says Zweifel.

Younger guides who have families sometimes try to stick to daylong climbs to minimise time spent away from their children, but they also may feel pressure to earn money because so much of the business depends on the weather that’s beyond anyone’s control.

“If you have a family, it’s not so easy to be a guide. You’re not going to get rich,” says Gianni MazzoneExternal link – a direct descendant of the Taugwalders – though he also is aware of how much more difficult things were for previous generations of his family who worked as mountain guides.

“In general, working now as a guide is much, much easier than before. The equipment – can you imagine – they didn’t have crampons. They had axes, but heavy, long ones. They had heavy clothes. It was definitely more difficult. It was difficult for them to get clients. The train stopped further down the valley, so guides had to walk down [to them], stay overnight, try to advertise to get clients, mostly British clients. Mostly they had cows, or other animals, sometimes sheep, so somebody had to look after the animals while the father went up to the peak.”

Often times, other family members worried each day if a guide might not come back – though the risk of being a guide has not necessarily diminished. With more access to the mountains, guides can get out with clients seven days a week in good weather. That means guides can get tired and are more often exposed to danger. “It’s like Murphy’s law,” Mazzone says, only half-joking.

“I’m still really motivated to do the work. But at the end I have to bring my client back safe from the mountain, and that’s the point, the priority, and not that I have a huge bank account.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.