Gold jumps on the green bandwagon

Can a gold bar, the shiny end-product of a complex and polluting process, really be carbon neutral? Yes, according to MKS PAMP, a Geneva-based refiner that wants to help make the gold industry more sustainable and environmentally responsible.

The precious metals group launched two carbon neutral gold bars in late July, the result of a more than one-year effort spearheaded by Tamara Jomaa-Shakarchi, the daughter of MKS PAMP’s CEO who heads the company’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) team. She says there is growing demand for carbon-neutral products.

“We’re trying to see if now people actually are going to walk the walk, they did the talk,” says Jomaa-Shakarchi, an Ivy League graduate who became head of the ESG team in January 2021 and oversees the company’s philanthropy division. “A consumer can now buy MKS PAMP gold, and know exactly where the GHG (greenhouse gas) missions are, like on the nutritional label of a cereal box, and how much carbon emission is related to your product. But then we take it one step further: we purchase carbon credits that offset the emissions related to the gold.”

Climate neutral and carbon-neutral labels have spread like wildfire across goods and services since the 2015 Paris Agreement to combat climate change introduced the world to the concept of carbon neutrality, although there is, as yet, no common agreement on how best to achieve this. One approach is to use carbon offsetting schemes to compensate for emissions that can’t be reduced, but these are not without controversy. Clarifying standards and evaluating the merits of carbon offsets will be a key theme at this year’s UN annual climate change conference, COP27, that kicks off in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, on November 6.

The 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference delivered a landmark agreement to move towards carbon neutrality by the second half of the 21st century to mitigate the effects of climate change.

“Climate neutrality refers to the idea of achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by balancing those emissions so they are equal (or less than) the emissions that get removed through the planet’s natural absorption,” the UN says.

One way to reduce emissions and pursue carbon neutrality is to offset emissions by reducing them somewhere else. This strategy, known as carbon offsetting, has become increasingly popular among individuals, countries and companies to neutralise their emissions by funding an equivalent carbon dioxide saving elsewhere.

But there is disagreement over the merits of carbon offsetting schemes. Advocates say they are environmentally beneficial and necessary, especially when carbon emissions cannot be completely removed at the source in the absence of scalable technological breakthroughs. They provide an opportunity for gradual progress towards “net-zero” goals.

Critics say they remove incentives to address carbon emissions at the source and the lack of global standards on carbon offset markets creates opportunity for greenwashing projects that are not always completed or successful. Rich countries have the resources to pay for such projects creating a dynamic where poor countries are paid to offset while wealthier ones might continue to emit.

In the context of MKS PAMP’s offering, carbon neutrality means the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of each gold bar labelled as carbon-neutral have been measured across the product’s life cycle; a plan is in place to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases produced; and those emissions that can’t be cut are offset by supporting carbon avoidance projects. The process is certified by a third party, in this case the Carbon Trust, which says it has worked to standardise standards and measures for carbon emissions in different types of industries for nearly two decades.

These so-called environmentally conscious gold bars are part of MKS PAMP’s broader efforts to measure and address its carbon footprint across the supply chain – from mining and recycling to the refineries and bank vaults where gold bars are stored.

Sustainability versus profits

But it’s not easy getting efforts to make greener products valued and accepted. At a gathering of top executives at the World Economic Forum in Davos this year, CEO Marwan Shakarchi shared his frustrations. He recounted how the very same day that the CEO of a Swiss bank was telling him how much his financial institution was doing and spending on ESG, a trader at the same bank turned down an MKS product that was carbon neutral, ESG friendly, and a bit more expensive.

“The trader did not want to pay up because it affects his P&L [profit and loss account],” Shakarchi said. “This is one of the biggest frustrations.”

Shakarchi believes that it is not enough to have ESG goals at the top of an organisation, they need to become part of performance reviews processes, a measure he is now introducing at his company. This conviction also prompted him to join an alliance of Swiss CEOs and board members, launched at Davos earlier this year, to give sustainability a higher priority.

It’s little surprise that, like other metal production industries and industrial sectors, sustainability concerns are catching up with gold and, as a result, Switzerland. The Alpine nation is the world’s largest gold importer; it refines more than two-thirds of the world’s gold; it’s a hub for high-end jewellery and watchmaking; and Swiss banks play a crucial role in marketing bullion.

About 2,500 to 3,000 tonnes of the precious metal are mined annually around the world, in many cases with devastating effect on the environment and local communities, including the Amazon rainforest in Brazil and Ghana.

Gold’s carbon footprint

In 2021, the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) produced an in-depth report on sustainability in the gold supply chain and Switzerland’s role as a global hub. Drawing on a 2014 cradle-to-gate study assessing the environmental impact of 63 metals from extraction to the factory gate, the report estimates that producing 1kg of gold creates 12,500kg of CO2 emissions. That adds up to roughly 41.25 million tonnes for global gold production in 2019, almost three times higher than all transport-related emissions in Switzerland that year, including domestic flights, according to calculations based on 2021 data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

Gold mining and purification is also energy intensive relative to other metals, according to the WWF report. When all stages and processes are combined, producing 1kg of gold requires 208,000 megajoules of energy, compared to 3,280 for silver of 53.7 megajoules for copper, according to a study cited by WWF.

Using a cradle-to-grave approach, which covers a product’s entire life cycle, MKS PAMP calculates that a 1kg gold bar creates about 2,731kg CO2e (a unit used to bundle and compare the global warming potential of different greenhouse gases). It is currently developing a carbon-neutral minted gold bar, an ingot featuring the company’s signature Lady Fortuna. To offset the carbon emissions, it is supporting carbon avoidance projects in countries that are key to the company. These include an Indian Solar Photovoltaic project, a renewable energy project in Brazil; and a hydropower project in the Ivory Coast. The projects are certified by Verra, one of the many players offering quality assurance in the booming voluntary carbon offsets markets.

But MKS PAMP isn’t stopping there. It recently became the world’s first precious metals company to have carbon emission reduction targets that are approved by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), in other words in line with the Paris Agreement which targets a cut in emissions to keep the rise in the earth’s temperature within 1.5 °C. Jomaa-Shakarchi says conversations are now underway with suppliers – particularly gold mining companies – to actively encourage them to measure and disclose their carbon footprint.

“Some of them are more forward thinking and forward looking than others,” she says. “If we have a client that has no intention to reduce, has no desire to actually change its practices, to meet the environmental standards that we put for ourselves by 2030, we’ll have to reconsider the business relationship.”

All about production

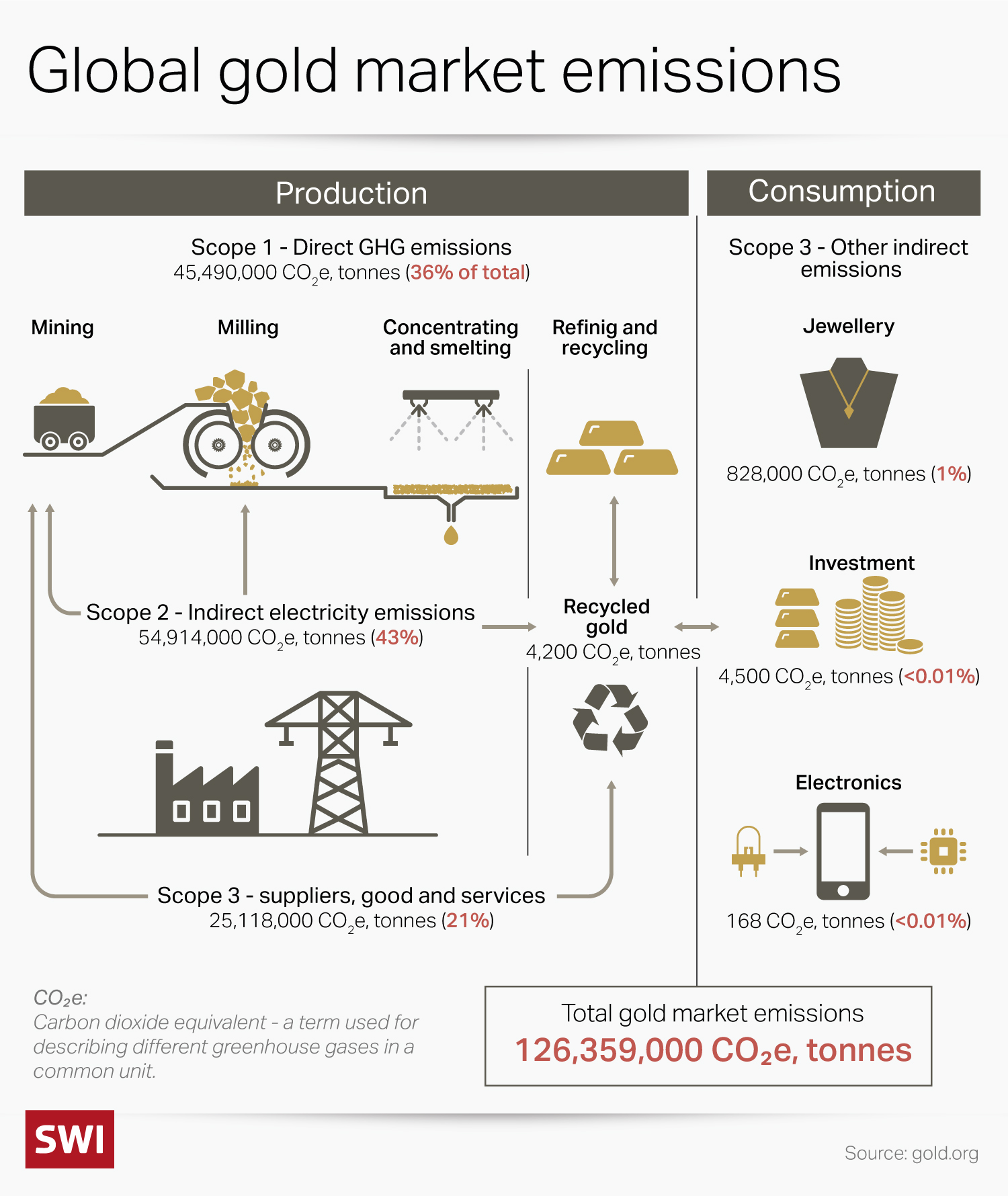

The World Gold Council (WGC) has been building a picture of the industry’s carbon footprint since 2018, when it realised how little data was available. The bulk of emissions are linked to the production process – on average about 80% of carbon emissions come from energy generated to support mining processes, which until very recently has depended on fossil fuels. Emissions relate to electricity bought from the grid (scope 2 emissions) or generated on site (scope 1 emissions) to power mining operations, machines and the milling process. Measurements are typically made in line with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the most common environmental data accounting tool.

When it comes to downstream activities – refining, product fabrication, jewellery-making, and even distribution and retail – carbon emissions are negligible relative to mining. “Once you’ve got a handle on the carbon footprint, and we spent years doing that, then you can start looking at what might be done about decarbonization,” says John Mulligan, the WGC’s climate change lead. “It’s all about the production process.”

The council estimates the annual carbon footprint of the entire gold supply chain to be 126 million tonnes of CO2, with most of the carbon relating to emissions from the production process. On October 19 gold industry representatives including the Swiss Association of Precious Metals Producers and Traders, which counts MKS PAMP and other major Swiss refineries among its members, signed on to a sustainability charter developed by WGC and the London Bullion Market Association. It includes a commitment to slash the gold industry’s emissions in line with the Paris Agreement and report on progress.

WGC members – primarily gold producing companies – had already agreed to participate in a task force on climate-related financial disclosures. That means they are obliged to understand both their own carbon footprint and agree to concrete plans to cut their emissions. Mulligan points to such developments as evidence that the greenhouse-gas-emitting segment of the industry is becoming more aware of its carbon implications and the need to formulate and disclose its climate action strategies.

“It means that the public or any stakeholder can view what the sector is doing in terms of its current carbon footprint, but also its future plans for emissions reduction,” he says.

In the meantime, the jury is out on whether green gold will do much to save the planet.

An ‘unnecessary’ resource?

Damien Oettli, head of markets at the WWF, is one of the sceptics. He questions the premise that gold could ever become environmentally sound. The way the precious metal is mined and traded today takes a heavy toll on nature and the environment, he says. Extraction takes place in areas with very high biodiversity, and the process pollutes water resources and the air. The processing stages that follow take place across the world. When forests are destroyed for mining, this has a negative impact on the climate as well as biodiversity. Artisanal mining brings the added burden of mercury pollution.

“All this is combined with the fact that gold is not a resource that is actually needed or used by humanity for survival,” he laments. “Compared to food production, it’s not an essential commodity that we depend on. So the damage that it causes has really no relation to the value it actually creates.”

Jomaa-Shakarchi is frustrated that efforts to make the gold industry more sustainable are often directly viewed as greenwashing – be it by environmental NGOs or customers who range from individual collectors and jewellers to banks. This limits the momentum for change.

“It’s true,” she says. “Gold is very impactful on the environment, but it doesn’t mean that we can’t try to help improve it.”

Nonetheless, she considers momentum for change to be growing. “I definitely think that people are now more willing to pay the premium, but it’s going to be an extremely long process.”

Edited by Nerys Avery

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.