Reframing the Swiss immigration debate

Discussions about immigration, in Switzerland and elsewhere, are often plagued by the prejudices and presumptions of both sides. A new book attempts to go beyond ‘pro’ vs ‘anti’.

“In Western Europe, most citizens prefer less immigration,” says Philipp Lutz, PhD candidate at the University of Bern and editor of the book Neuland (NZZ libro, in German). These days, this statement might come as less of a surprise than some years ago. But it nevertheless raises the paradox at the heart of migration policy in this part of the world: lots of people want less, but politicians are loath to stop it, both for economic and normative reasons.

It also seems a strange statement to make for a researcher who is, above all, interested in the benefits of migration. But for Lutz, and for the academics and contributors who fed into the book, subtitled ‘Swiss Migration Policy in the 21st century’, black-and-white visions of ‘for or against’ migration need to be shelved. “Immigration is often seen as genuinely good or bad, but this is not helpful,” he says. “It is first and foremost an evident social reality, whether one likes it or not.”

Indeed, the first of twenty ‘theses’ which the book presents, aimed at providing a visionary platform for redefining the migration debate, is precisely that: “migration of people is the historical norm.” Movement is something which has never stopped and will never stop, they say, and Switzerland is a paradigmatic case. Hence Thesis 3: “Switzerland is a classic migration country with high levels of inward and outward mobility.”

Re-framing the debate

The whole confusion, for Lutz, starts with the assumption that migration is a disruption to some imagined state of homogenous normality. The persistence of this idea is what spurred him and the think-tank foraus to launch a series of national discussions last year, leading to the book. What they wanted to do, he says, was to redefine some of the fundamental starting points of the migration debate, taking into account the expected growth in the importance of migration for Switzerland in the future (Thesis 4), as globalization continues to make the world more economically interdependent.

More

Vote on fresh ideas to tackle immigration policy

So, what other assumptions are they trying to counter? For one, that the social fact of migration can be completely influenced by political actions. Thesis 5 asserts that the causes of migration (economic disparities, personal aspirations) are structural and unstoppable, and escape policy prescription. Theses 6 and 7 go a step further, claiming that political attempts to overcome these structural realities will inevitably lead to circumventions, and that the chimeric appearance of fences and walls actually imply a loss of control.

Similarly, when it comes to one of the biggest bugbears of immigration opponents, the loss or dilution of a sense of national identity, the book again claims that this need not be the case. Things will always change, but not necessarily for the worse. Theses 17-19 laud the economic and creative value of diversity in a country, and even claim that “the Swiss identity as a Willensnation (a country founded not on ethnic homogeneity but on a ‘will’ to cooperate for civic and political ends) can be strengthened by migrants.”

Lutz explains: “immigrants are often expected to adapt to a national culture perceived as homogenous”. But the social reality is different: even without immigration, societies are increasingly diverse in terms of values, lifestyles and cultural orientations. A nation is not set in stone. It is a constantly evolving entity, a “project”: one which he would prefer to see based on “a more civic-political rather than ethnic cultural understanding, which could better embrace the reality of migration.”

One way to begin working on this is to somehow facilitate the process of citizenship granting, which is one of the slowest and most cumbersome in Europe. “In Switzerland, one-quarter of the population still has no voting rights,” he says. As this figure grows, various risks can arise, such as “an ever-growing democratic deficit, social marginalisation, and a sense of exclusion.” Including more immigrant voices in political and community debates, he claims, could increase their “sense of belonging” and “strengthen social cohesion.”

Reality check

Debates about migration in Switzerland, as elsewhere, also frequently (and perhaps understandably) fall into a mode of comparing numbers. How many people are arriving? How many are leaving? How do they correlate with current GDP figures? To such an extent that the numbers become politicized, as happened recently when a batch of SECO figures about the economic benefits of free movement came under fire from the conservative right, who accused the government of propagating “fake news.”

More

Opposition to immigration remains strong in Switzerland

What does Lutz think about these debates? Again, the arguments are misplaced: too much focus around numbers rather than policy outcomes, he says. Just as GDP figures cannot capture the mood of a nation, migration numbers are not enough to fully show the bigger picture. As for the linkages between migration and economic development, this is implicit in Thesis 9: “migration is the consequence and catalyst of economic development.” But to overly ‘economise’ the argument again risks “falling into the trap of tolerating migration as a necessary evil for economic gain,” rather than “managing it as a reality that affects the whole of society.”

If all this might sound like futile academic theorizing rather than clear political prescription, it’s worth noting how discourse can mobilize and drive policy. Witness the recent uproar when, on July 31, the eve of Swiss National Day, socialist politician Ada Marra posted on Facebook that “ONE Switzerland does not exist.” “The people who live there exist,” she wrote. “With different ideas and opinions. With different passions and orientations. With different priorities and preoccupations.”

Within a few hours, the message – which sounds strikingly similar to the type of open reappraisal Lutz suggests – was assailed by expletives, and Marra considered closing her page to comments. The next day, she was speaking to Swiss public broadcaster RTS, defending her statement against conservative right politician Michaël Buffat, whose opinion is indicative of many: “Switzerland is not a pile of individuals, it is the sharing of unique common values: independence, neutrality, direct democracy, work.” We have a “common destiny,” he said.

Newland

More

Anti-migration initiatives have long tradition

For Lutz’s Neuland project, such debates are welcome. What foraus wants to do, he says, is contribute to the much-needed debate around how Switzerland can reconcile its self-image with the reality of being a country of migration. This debate should involve as many people as possible, and from both sides of the “divide”: those who see migration as a threat and those who see it as an enrichment.

And so, the next step is to kick off another national tour, he says, to promote and debate the ideas in the book and use them to continue discussions of how policies can focus more on making migration beneficial for society. The “town-hall style” discussion groups and crowdsourced platforms which led to the book will also be recycled for use in other policy areas.

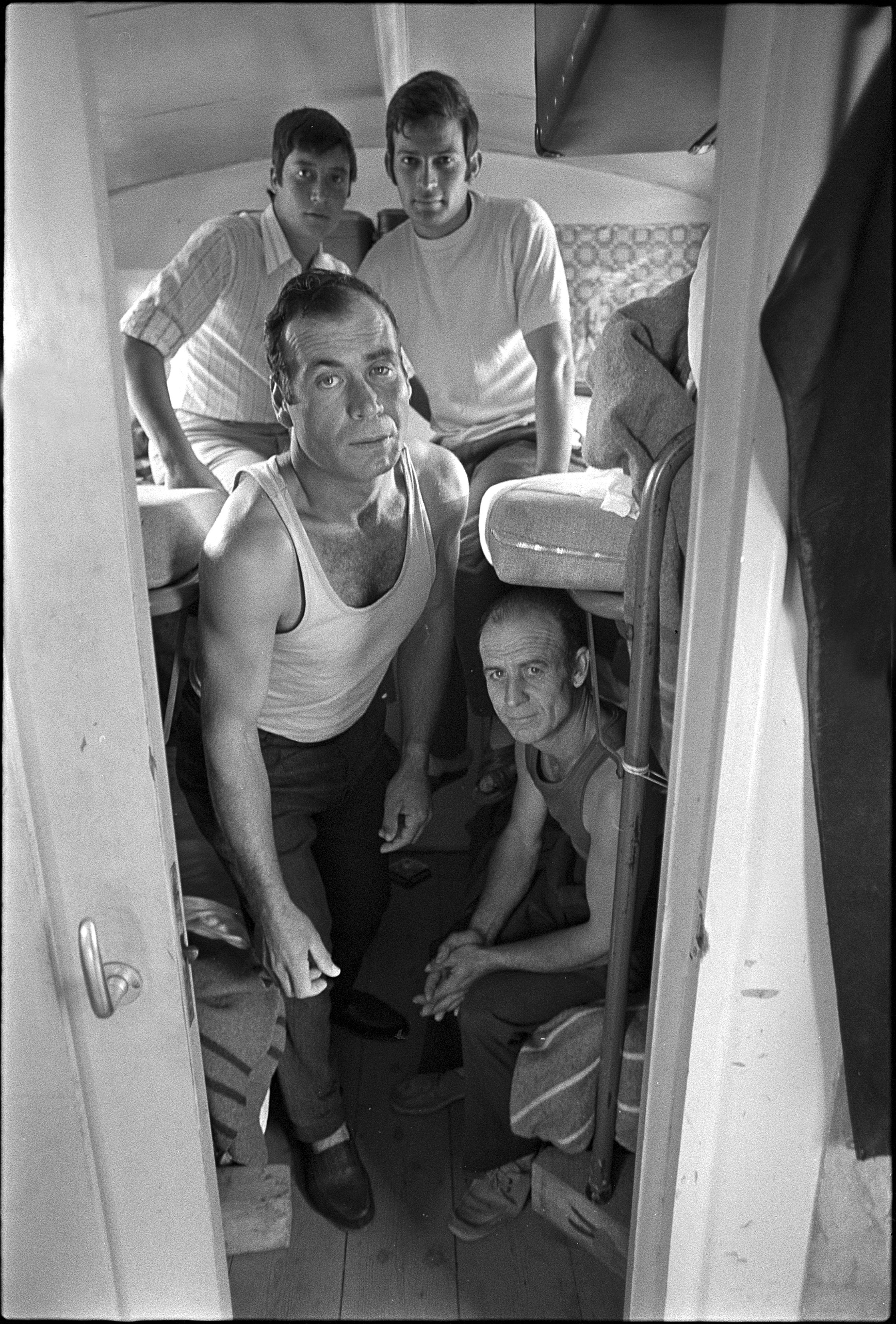

And for the future of migration in Switzerland? He is “optimistic,” despite the current ranklings, which in any case “are not new”. And while in the 1970’s the so-called Schwarzenbach initiative that aimed to expel hundreds of thousands of Italian ‘guest workers’ was only narrowly defeated, the more recent decision to implement a ‘light’ version of the approved initiative against mass immigration in 2014 (see embedded story) did not cause much political uproar: “Swiss people are more and more willing to accept migration as part of the country’s make-up,” he said.

The 20 Theses

1. Migration is a historical normality

2. Migration is a liberal value and therefore politically worthy of protection

3. Switzerland is a classic country of migration with high mobility in all directions

4. The importance of migration for Switzerland will continue to increase in the future

5. The causes of migration are structural and largely escape policy prescriptions

6. Political attempts to prevent migration lead systematically to circumvention strategies

7. Fences and walls are a symptom and cause of a political loss of control

8. Porous barriers act as revolving doors and facilitate mobility in all directions.

9. Migration is the consequence and catalyst of economic development

10. Countries of origin benefit from migration through the valuable flow of money, knowledge, and ideas

11. Migration is an effective way to improve personal life opportunities

12. Migration drives Switzerland’s prosperity and favours investment in the future.

13. Safe escape routes are necessary to protect persecuted people

14. The causes of conflicts are complex and multidimensional

15. Refugees are seeking new life perspectives

16. Granting asylum to persecuted people contributes to a freer and more secure world

17. The equitable participation of the migrant population strengthens social cohesion

18. Cultural diversity creates values for society and business

19. The Swiss civic identity can be strengthened by migrants

20. With a self-image as a country of migration, Switzerland can be ready for the future

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.