As climate changes, so do borders

Confirmation that glaciers between Switzerland and Italy have drifted over the decades has sent both sides to the drawing board to redefine parts of the border.

A line of around 750km, established in 1861 and fixed based on data from 1940, would have to be adjusted on account of rapidly melting snow and ice in the high Alps, including in an area around the famed Matterhorn.

But the issue of redrawing a small section of the divide between the countries – no more than ten per cent – is as much about warmer temperatures and shifting glaciers as how the two countries agreed to define the border almost 150 years ago.

It is a technical exercise, both parties say, and hardly one either side is wrangling over. Rather than negotiating a new border, bureaucrats are looking to see whether particular markers have shifted. And in the case where they have, they redraw the lines.

At lower altitudes, borders are defined at fixed points – literally with cement markers in some places – said Daniel Gutknecht from Switzerland’s topographical service.

Straight lines

“In the middle lands, the border is a straight line between points. In the high mountains, they did not want that and also it was not necessary. Those before us defined the borders in words,” he told swissinfo at the organisation’s headquarters just outside Bern.

“The best way to explain it is to say that there are natural landmarks that the border passes through,” explained Gutknecht, who is responsible for coordinating Switzerland’s border with other countries. “And we just match our border to these natural changes. The same happens in the middle lands with the rivers.”

In the high altitudes it was easier to separate Switzerland from Italy in some places than in others. “If it’s like the edge of a knife, it’s well defined and easy to recognise,” he said.

In other cases officials might have defined the border as the highest point on a particular glacier or the spot at which water would flow to one side or another. Theoretically, as the terrain changed, the borders should have too. But they didn’t.

“If you didn’t do it, you would have borders that are unrealistic,” Gutknecht said.

New map

“Previously this rock face was covered with ice,” he said, pointing to a spot across the Italian border near the Matterhorn. “That was once the glacier. Once. Underneath is rock and that was like that in 1940.”

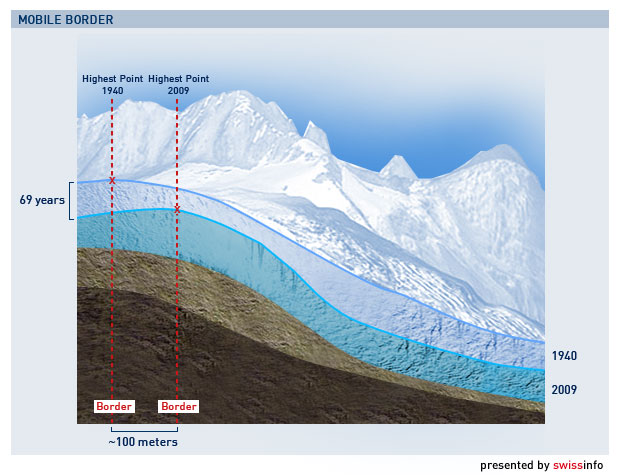

Today the glacier’s highest point holds a spot in what was once its shadow. “Now the highest point is here,” Gutknecht said. “And between here and here is the difference. This can be up to 100 metres.”

Gutknecht has a map of the new border but was unable to release it. Switzerland’s foreign minister has yet to sign off on it and before Italian politicians do the same, the changes remain unofficial.

In Italy it requires a change of law and the concept of a so-called “mobile border” has to be debated in the Italian parliament. There, the decision is made through political channels.

Even so, it is a relatively uncontroversial move for both sides.

“During the regular and routine reconnaissance operations and maintenance of boundaries, experts in both countries have over the past four years noticed a movement of the glaciers,” said Carlo Colella, the director for Florence’s military geography institute.

“No direct consequences”

The situation could be different in other parts of the world, where borders are disputed or where access to natural resources is at play. In this case, Italy and Switzerland say the difference is negligible.

“The new border will have no direct consequences for individuals,” Colella told swissinfo. “Variations of ten metres do not affect either country. Relations between the states are marked by a longstanding collaboration.”

Both sides have agreed to establish a new methodology for examining the Swiss-Italian border. Italy has also formed pacts with neighbouring France and Austria. Switzerland also shares a border with the two countries but the mountains on the country’s eastern and western borders are not high enough to be affected by shifting glaciers.

Switzerland’s topographers also want to make sure data are up-to-date for hikers and climbers. The proliferation of global positioning systems – including those in mobile phones – has had an impact on the pace at which authorities are responding to the latest geographic changes.

Swiss authorities conduct a complete survey of the border with Italy every six years and Gutknecht said that while updates are being made now, there is no schedule for updating the border.

“For us, the border is fixed to the moment of observation and stays fixed,” he said. “Even if things change, it doesn’t matter to us – until the next observation.”

The next observation could be “two years, 100 years, or two months: out of necessity.”

swissinfo, Justin Häne

Around ten per cent of the 750km border between Switzerland and Italy will be affected and will in some places move 100 metres at most, authorities say.

When the border was devised, officials defined it along text descriptions, which now have to be matched to geographic coordinates.

The border should have changed as glaciers moved, but it has not up to now.

Daniel Gutknecht from Switzerland’s topographical service says that as rock faces become exposed, officials will be able to determine more permanent spots to mark the border.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.