Black Spider: horror made in Switzerland

Jeremias Gotthelf’s 1842 novella The Black Spider is a classic of Swiss literature – and a rare example of horror made in Switzerland. Cinema and literary critic Alan Mattli questions whether a new cinematic adaptation can help it break through internationally.

Did you know that Switzerland is the birthplace of the horror genre as we know it today? It may have come by this honour somewhat passively, in part through climatological happenstance, but it is a story worth telling. It was here, on the shores of Lake Geneva, that a young MaryExternal link and Percy ShelleyExternal link spent the summer months of 1816, hosted by the poet Lord ByronExternal link and his friend John Polidori.

Kept from outdoor activities by bad weather – the result of a volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora the year before – the quartet took to telling ghost stories: Mary Shelley presented the rudiments of her seminal science-fiction novel Frankenstein, while Byron’s musings about vampires would later serve as inspiration for Polidori’s 1819 story The Vampyre, itself a future touchstone of 19th-century vampire lore, including Bram Stoker’s 1897 masterpiece Dracula.

Much of Switzerland’s place in the annals of horror, then, is owed to the fact that both Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster are Swiss-born, so to speak. Horrific writing, meanwhile, was done elsewhere, at least in the popular consciousness – by Shelley and Ann RadcliffeExternal link in England, by Edgar Allan PoeExternal link in the United States, by E. T. A. HoffmannExternal link in the German lands, by the Marquis de SadeExternal link in France, among other 19th-century so-called gothic and horror writers.

Swiss literature in the 19th century, by contrast, was dominated by the more sober realist mode; by the slice-of-life tales of Gottfried KellerExternal link and the historical narratives of Conrad Ferdinand MeyerExternal link. But just as Switzerland seems an unlikely place of origin for two staples of Halloween iconography, there is a Gothic underbelly to that supposedly quaint Swiss-German realism – one that is rarely appreciated beyond the borders of German-speaking Europe.

A warning against evil

Enter author and Protestant pastor Albert Bitzius, better known under his pseudonym as Jeremias Gotthelf. Born in 1797, he is generally considered, along with his juniors Keller and Meyer, to be Switzerland’s major literary figure in the 1800s, specialising in realist accounts of rural life in his native Bernese Emmental, written in a playful mélange of German grammar and vocabulary borrowed from the regional dialect.

And it is maybe his most enduring work, the 1842 novella Die schwarze Spinne (The Black Spider), which provides us with a rare example of Gothic horror made in Switzerland.

However, much like calling Switzerland the birthplace of modern horror comes with a few qualifiers, so does calling The Black Spider a horror story.

For one, it’s debatable whether Gotthelf himself would agree with this assessment. Framed by a comical bit of rural realism, detailing the logistical challenges of an 1840s baptism in the Emmental town of Sumiswald, the novella has the didactical structure and the stern moralism of an allegorical Christian sermon: it is, in essence, pastoral propaganda – a warning against evil temptation and an illustration of the transcendental power of godly devotion.

Yet the methods of Gotthelf’s religious instruction are steeped in Gothic sensibilities, with the main story, set 600 years earlier, featuring unnerving medieval architecture, demonic apparitions, a Faustian pact, and an infernal supernatural infestation.

Ordered by their liege lord, a capricious knight of the Teutonic Order, to construct a shaded avenue leading to his castle, the people of 13th-century Sumiswald are accosted by the devil, who promises to do the gruelling, near-impossible work for them, if they yield unto him an unbaptised child.

While the village men are too afraid to agree to the bargain, Christine, a German immigrant, takes it upon herself to keep Sumiswald safe from the knight’s wrath, sealing the deal with a kiss. The devil keeps his word, but the villagers promptly attempt to double-cross him, resolving to henceforth baptise every new-born child instantaneously.

As Satanic punishment, a mark on Christine’s face begins to gradually take the shape of a spider. After another successful baptism, the mark, in a masterful moment of grisly body horror, finally breaks open and gushes forth a mass of spiders, which kill all of Sumiswald’s livestock – and which are merely a harbinger of the black spider of the novella’s title and the plague-like devastation it wreaks.

Adaptation pains

The Black Spider finds its horror in its blend of folk memory – the eerie cultural afterglow of past epidemics – and fervently Christian cautionary tale, reminding readers of the hell that is conjured up when a community experiences even the slightest lapse in religious commitment.

As such, it has, perhaps understandably, proven somewhat immune to broadly accessible adaptation over the years, which might be why the text has hitherto struggled to transcend the language border.

Whereas Gotthelf’s two-part bildungsroman Uli the Farmhand (1841) and Uli the Tenant (1849) was adapted by director Franz Schnyder into two classics of Swiss cinema in the 1950s, The Black Spider’s journey across different media has been a more uneven one.

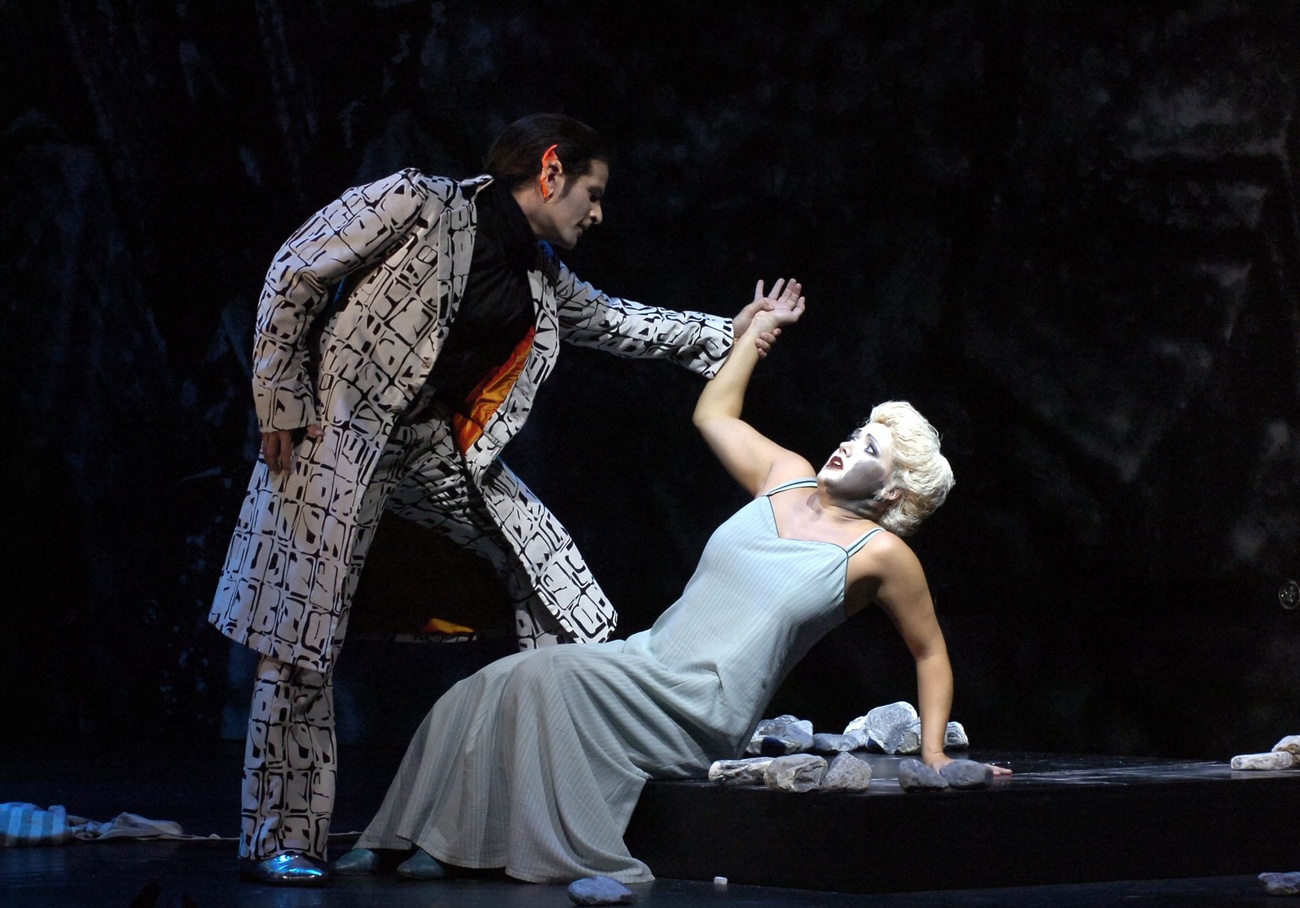

There exist a handful of stage versions – most recently a Frank Castorf-directed mash-up with Mikhail BulgakovExternal link’s Master and Margarita – as well as several radio plays, a 1983 film, and a 2022 film that is set entirely in 1250s Sumiswald, and which is currently playing in Swiss cinemas.

From theological to psychological

According to Barbara Sommer, who co-penned the 2022 version, Gotthelf’s worldview is in many ways antithetical to modern tastes. “You can’t tell that story the way it was written down. There is something reactionary about the source material,” she says, referring to the original text’s casting of Christine as a weak-willed Satanic accomplice, a suspicious foreign woman who, like Eve, gives in to temptation out of godless short-sightedness.

The challenge Sommer and co-writer Plinio Bachmann set themselves was “to leave the tale in its historical situation, but also to adapt it in such a way that its message becomes more appropriate, more legible, more interesting for us today.”

So unlike Mark Rissi’s wildly successful 1983 film – a mostly unsophisticated retelling that is remarkable only for replacing Gotthelf’s pastoral frame narrative with a short film about four youths looking to score some heroin – 2022’s The Black Spider seeks to complicate the role of Christine. In Sommer and Bachmann’s telling, her pact with the devil is framed as an act of moral courage; and the horrors that befall Sumiswald as a result come to resemble a purge of the village’s misogynist bigotry.

“I think we’re actually pretty close to Gotthelf. We’re just stressing different elements of his story,” says Bachmann, reflecting on these rewrites. “We’ve shifted the treatment of good and evil from the theological to the psychological.” As director Markus Fischer puts it by way of summary: “Gotthelf is in there, but it’s a new Gotthelf.”

Yet even though Fischer’s Black Spider is a Swiss-Hungarian co-production shot in High German and featuring a cast of notable actors from both Switzerland and Germany, it remains questionable whether it can alert the wider world to the Gothic delights of Gotthelf’s novella.

For not only does this version de-emphasise the book’s more striking supernatural elements, folding them into a more conventionally told historical drama. It also does not display an explicit interest in fostering curiosity about its source material, having been made by and, maybe inadvertently, for people to whom Gotthelf is an instinctively familiar name. Whatever the reason, it would seem that Switzerland’s role in the popular understanding of the history of horror remains, for now at least, a passive one.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.