The Alps prepare for a new facelift

Does artificially elevating the summit of the Matterhorn’s little sister or performing cosmetic surgery on another peak compromise the integrity of Switzerland’s mountain landscapes?

The battle lines have been drawn between the mountain transport companies behind the plans and environmentalists who have banded together to keep the peaks from undergoing the scalpel.

Nature protection organisations fear plans by the village council in Zermatt to rezone the area around the Klein (little) Matterhorn will be the green light the local ski lift company needs to alter its appearance by hammering a needle nose 117-metre-high tower into the top.

The tower, which could house a hotel and restaurant, would raise the mountain to the magical height of 4,000m.

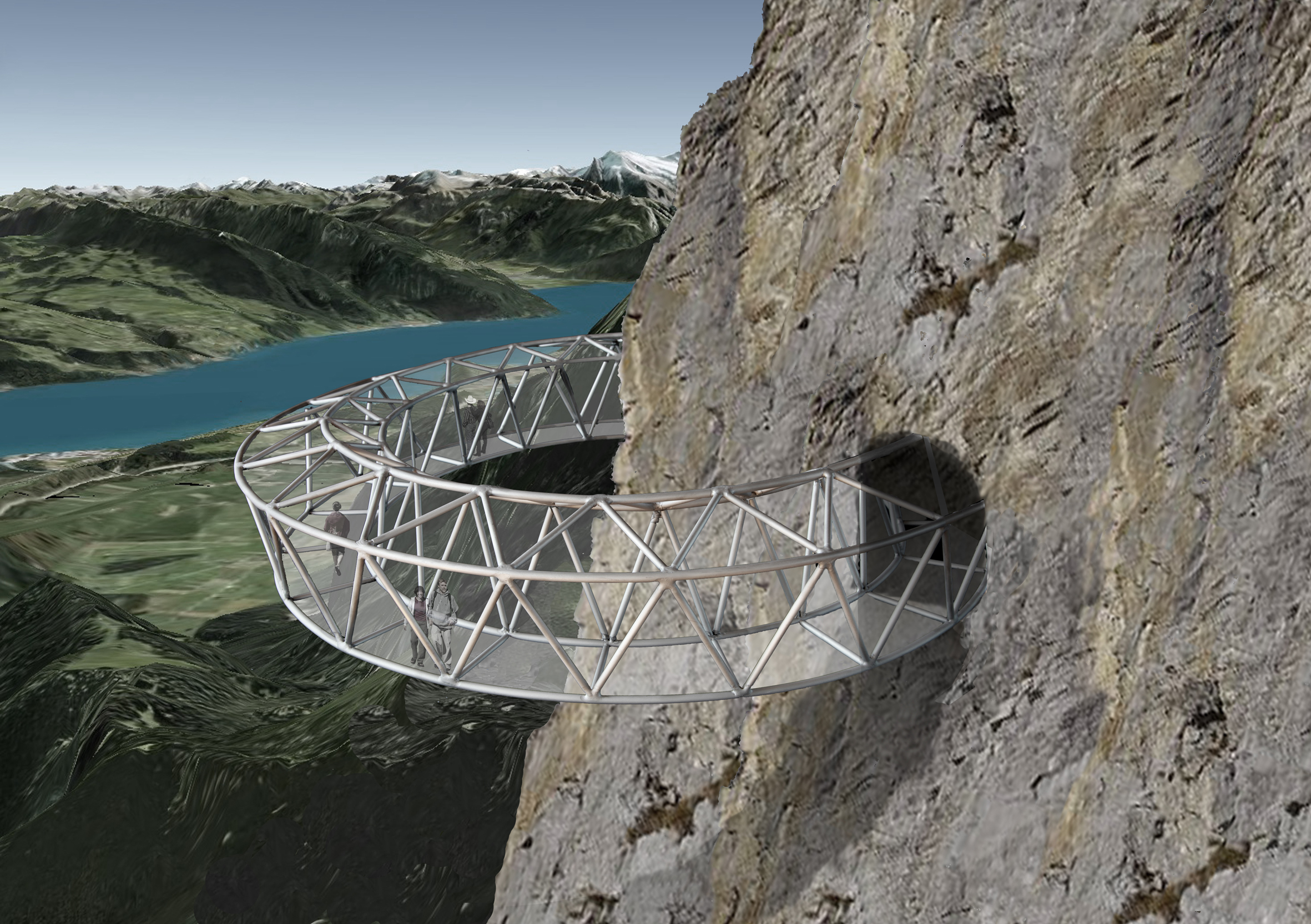

And green groups are also fighting a project to pierce the square rocky face of the Stockhorn mountain with a skeletal observation deck.

A pygmy of a peak in comparison to the Klein Matterhorn, the Stockhorn measures a mere 2,190m above sea level, but it’s iconic since it’s the first prominent summit seen rising above the plains as you journey south from the capital Bern towards the Alps.

The coalition of opponents include the Swiss branch of WWF, Pro Natura, the Swiss Foundation for Landscape Protection (SL) and the Swiss Alpine Club (SAC).

Arms race

The groups claim the tourist companies behind the plans are showing no regard for the natural mountain landscapes in their bid to keep one step ahead of the competition by erecting spectacular high altitude structures.

In their formal objections, the environmentalists claim the projects are part of an “arms race” among the companies across the Swiss Alps that operate ski lifts and other mountain infrastructure, which includes cable cars, hotels and restaurants.

And there is some truth in the argument. There are more than 500 companies that own mountain transportation systems. In total, they maintain nearly 1,800 ski lifts, cable cars and mountain railways and to stay in business must win over increasingly spoiled tourists who demand more than a view from the top.

Alfred Schwarz, manager of the Stockhornbahn company whose cable car whisks people to the summit with its spacious mountaintop restaurant, confirmed this to swissinfo.ch, arguing that the only way to guarantee the long-term survival of the enterprise was to go ahead with the building of the controversial observation deck.

Schwarz said the unique structure would give visitors the chance to stand outside the mountain and feel like a “mountain climber” clinging to the near vertical face.

It would cost around half a million Swiss francs and the investment would be recouped in a few years thanks to the income generated by additional visitors (estimate +8-10 per cent) attracted to the new platform.

Hypocritical

While the manager says he expected objections from environmentalists like the WWF or SL, he sees the stance of the SAC – which represents alpinists and mountain hikers, and maintains a large network of mountain huts – as hypocritical.

“The mountain huts they build are quite enormous; just think of the recently completed Monte Rosa hut, which has been a disaster regarding its claims of using renewable energy,” Schwarz told swissinfo.ch, referring to the finding that propane gas or rapeseed oil used to provide the electricity in the high-tech building’s kitchen has to be flown in by helicopter.

Schwarz insists the ring-shaped platform will not disfigure the Stockhorn’s face, extending a mere eight metres from the rocky wall and measuring only 2.5 metres high. He is hopeful the authorities will approve the project and it can be completed during the 2011/12 winter season.

However, due to the Swiss system of checks and balances, groups like the coalition opposing the Stockhorn and Klein Matterhorn structures have the right to appeal against projects that may impact on a protected area or require a parcel of land to be rezoned. They are often successful when cases are taken to court.

The Klein Matterhorn is a zoning issue, while the environmentalists claim the Stockhorn is part of a protected landscape.

Case by case

Courts take decisions on a case by case basis, says Lukas Bühlmann of the Swiss Association for National Spatial Planning.

“If a mountain already has a cable car on it or other infrastructure, it’s normally easier [to win approval]. But if it’s a mountain still untouched then it’s a different question – or if it’s in a protected area,” Bühlmann told swissinfo.ch.

“If a case goes to the federal court, an evaluation would be based on how large the new structure is going to be and how great the influence would be on the landscape.”

Raimund Rodewald, who heads SL, says the latest plans are yet another expression of turning natural environments into money-making playgrounds which are as accessible as shopping centres or cinemas.

“Mountain access by cable car is already a negative part of the history of tourism in Switzerland, and we believe it’s become an ethical discussion,” Rodewald said.

“Not only is nature at high altitude being destroyed, but our attitude towards nature as well.”

The first hotels were constructed on mountaintops in the 1830s, and the initial building boom culminated during the period at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century known as the Belle Epoque.

The first hotels were only accessible by foot or mule but the paths would eventually be replaced by mountain railways, either cog or funicular systems, the most spectacular being the Jungfrau Railway completed in 1912. This railway’s trains take tourists to the saddle – or Joch – of the Jungfrau at 3,454m via tunnels blasted through the adjacent mountains, Eiger and Mönch.

The second building boom started in the 1960s as tourism took off thanks to Europe’s post-war economic recovery. Cable cars and gondolas and chairlifts became the mechanical transport means of choice.

According to the Swiss association representing the interests of the country’s 500 mountain transport companies, there are 1,796 cable cars, ski lifts, funiculars and cog railways servicing Switzerland’s mountains. The highest takes tourists to a 3,820 metre-high station just below the summit of the Klein Matterhorn. Switzerland also boasts a rotating cable car, the world’s first double-decker gondola and plans have been drawn up for the first split-level gondola that has an open upper deck.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.