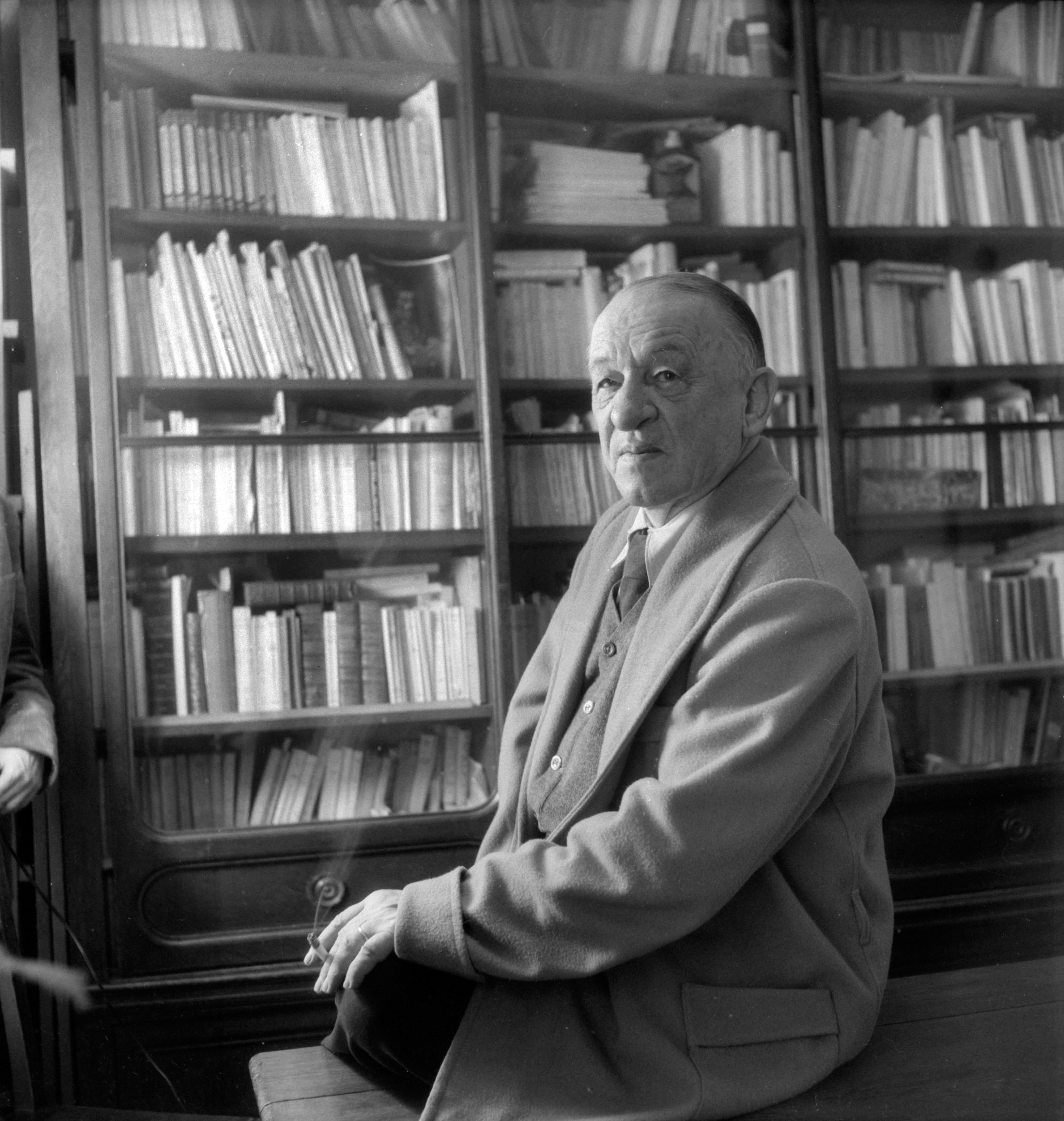

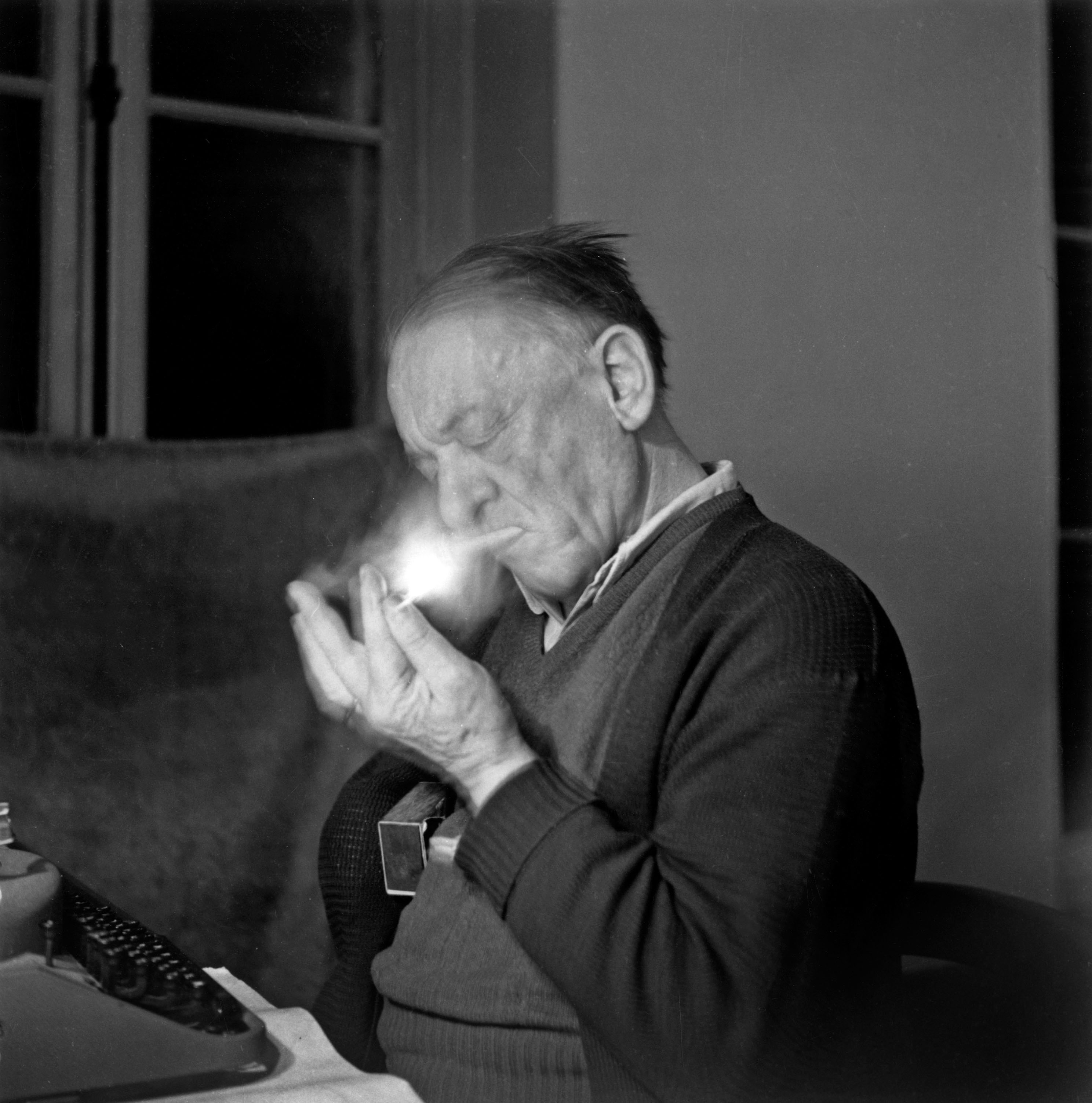

Writer Cendrars joins French hall of fame

Little known in the English-speaking world, Swiss author, anarchist and war correspondent Blaise Cendrars has been confirmed as a pillar of French literature with the inclusion of his autobiographical works in the prestigious Pléiade collection.

Cendrars is not the first Swiss writer to join the celebrated collection curated by Gallimard, one of France’s most influential publishing houses. Before him came Benjamin Constant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and, more recently, Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz.

The unconventional Cendrars doesn’t quite fit in with these writers. His reputation is first and foremost as a poet, who made a name for himself internationally with his lengthy poem Trans-Siberian, about a journey he made across Russia in 1905.

The poem itself was not published until 1913, along with almost abstract illustrations by Sonia Delaunay. The book is considered by some experts to be a modernist icon, while Cendrars himself referred to it as “a sad poem printed on sunlight.”

But he was also a novelist, an extravagant writer who took breaks of several years between the beginning and end of a novel. He began writing Lice, the second volume of his Memoirs, in 1917, only to finish it in 1946.

More

Blaise Cendrars – a restless travel writer

Difficult subject

“Cendrars needs time, it [his work] is something to ruminate over, making it a difficult subject for critics, thrown by the lack of continuity in his literary output. It took specialists a long time to recognise in him as having produced a great body of work,” said Pléiade editor Claude Leroy.

“Twenty years ago, having this writer in the Pléiade collection would have been unimaginable. Today it seems obvious because his work has since revealed its coherence.”

The opening of the Cendrars archives in the Swiss capital Bern in the early 1980s allowed researchers to show how the author was received different countries.

Cendrars had varying degrees of impact in different places, his success depending not only the country but also on the translations of his work.

“French-speaking sub-Saharan Africa discovered him thanks to his African Folktales, published in 1921. The book may seem antiquated today, but at the time of its publication it was as important as the discovery of black art by cubist painters,” Leroy explained.

Moderately appreciated

The translation of Cendrars’ texts in the United States is on the other hand only partial.

“Thanks to a literary agent in North America, Cendrars was able to publish his first novel, Sutter’s Gold, in English,” Christine Le Quellec Cottier, director of the Blaise Cendrars study centre in Lausanne and Bern said.

“The difficulties came with his Memoirs and especially with Moravagine, a work in which Americans saw violence, a certain form of anarchy and a nihilism linked to the Russian Revolution. It took many years before he was appreciated in the United States.”

“Moderately appreciated,” Leroy adds, who is of the opinion that Cendrars has still not found the place he deserves in America.

“Over there, he is always seen as a marginal figure, with the exception of the underground circles where he has his readers and admirers. Patti Smith, for example speaks highly of him,” he said.

Cendrars would not be considered politically correct either today.

“His hatred of the Germans, repeated in his Memoirs (Lice, I Have Killed) has not contributed to any success in Germany although it has to be said most of his writings have been translated there,” Leroy pointed out.

1887 : Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds.

1894-1896 : The family moves to Naples.

1897 : Returns to Switzerland where he attends the Untere Realschule in Basel.

1902 : Business college of Neuchâtel.

1904-1907 : Moves to Saint-Petersburg where he works for the Swiss watchmaker Leuba.

1911 : Travels to New York where he struggles to adapt to the American way of life.

1914-15 : Joins the French army and loses his arm in action.

1916 : Becomes a French citizen.

1924-1927 : Three long trips to Brazil.

1939-1940 : War correspondent with the British army. He spent the rest of the war, listed as Jewish, in Nazi-occupied Paris.

1943-1949 : Writes his Memoirs

1950 : Returns to live in Paris.

1960 : Commander of the (French) Legion of Honour

1961 : Death

Homeland rejection

Cendrars’ reception in French-speaking Europe was quite different. “In Belgium, in the early 1920s, he was everywhere, helped by Robert Guiette, a young Brussels intellectual who admired him, inviting him several times and introducing him to the Belgian literary circles as an avant-garde poet,” said Le Quellec Cottier.

And in France? Cendrars felt so much at home there that he went as far as joining the French Foreign Legion during the First World War.

That decision cost him his right arm and saw him rejected by the neutral Swiss. It took until the centenary of his birth in 1987 to see a reappraisal of Cendrars by the country he had always loved. Although he had travelled extensively, he believed Switzerland encapsulated all the beauty of the world.

Pierre Lazareff, a major French editor, asked him one day to write a reportage about Switzerland.

“You will see, I will show you a country stranger than the Windward Islands, the Amazon or central Africa,” Cendrars responded.

How strange remains a mystery. Cendrars suffered a stroke in 1957 and the assignment was never carried out.

(Translated from French by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.