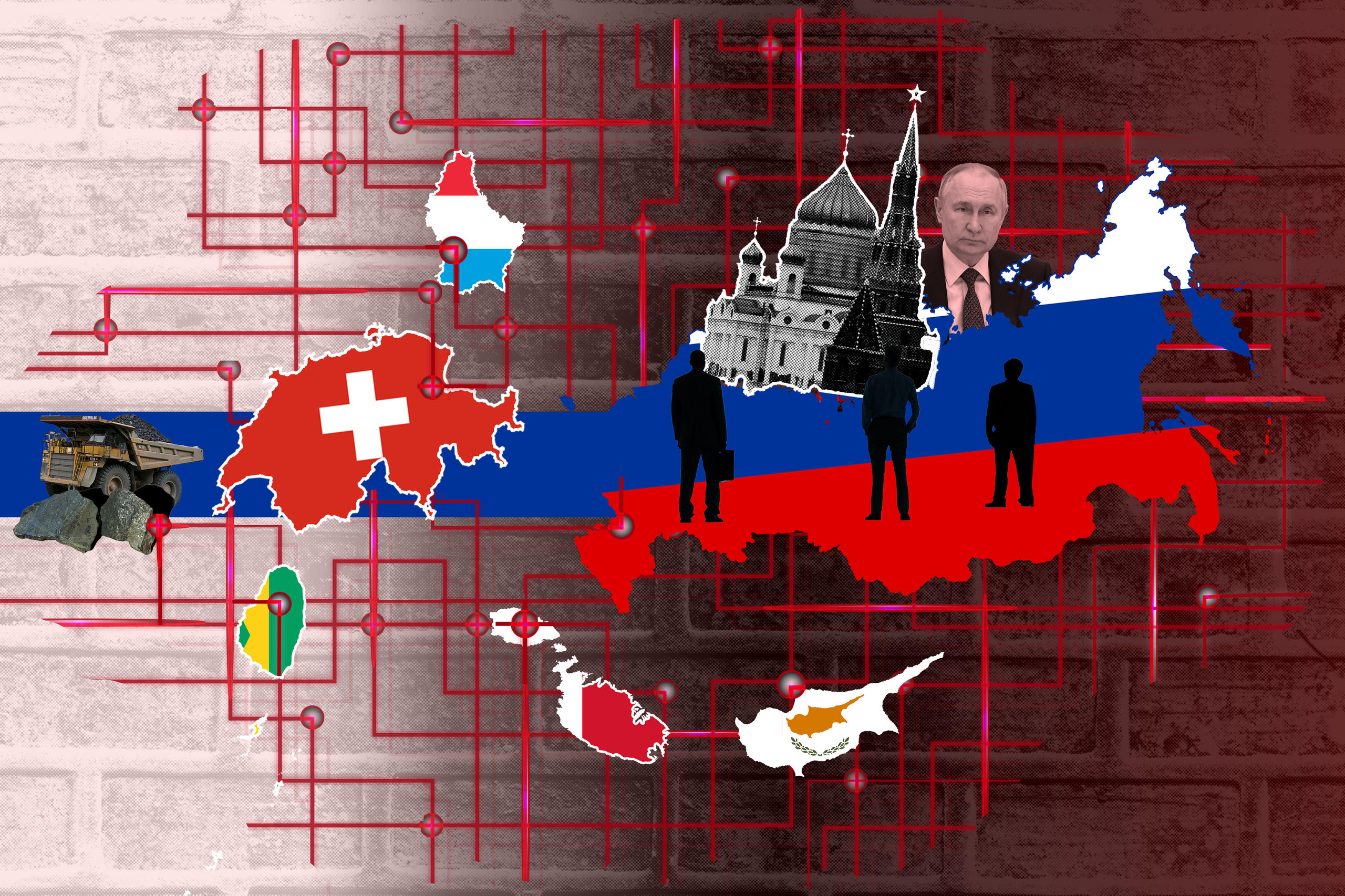

Mark Pieth: ‘Switzerland muddles on with sanctions’

Trade in Russian oil and gas is shifting from commodity trading hub Geneva to Dubai and Singapore, says anti-corruption expert Mark Pieth. But this is not the outcome of greater efforts to implement sanctions against Russia by Swiss supervisory authorities. Pieth explains why the economic fight against Moscow is fizzling out.

SWI swissinfo.ch: The sanctions against Russia have not yielded lasting results. That’s not an anomaly, but you also consider it a political failure on the part of the West. Why is that?

Mark Pieth: There are only a few cases in history where sanctions have worked. The sanctions against [former dictator of Iraq] Saddam Hussein are one example. But here, too, an exception had to be made and oil had to be exchanged for food because they didn’t want to harm the Iraqi population.

By comparison, a country the size of Russia has a multitude of workarounds. And the West has made mistakes. It underestimated how dependent it was on Russian oil and gas. Germany could break away, Hungary and Austria could not.

People thought they could bring the Russian economy to its knees. There were people who argued that the Russian economy was about the same size as the Italian economy. But Russia’s strengths lie in its trade of raw materials – and our dependencies on it.

SWI: Quite a few countries, including India and China, continue to cooperate with Russia. Doesn’t this limit the effectiveness of Western sanctions anyway?

M.P.: It is indeed difficult to achieve anything without greater unity. India buys cheap oil from Russia. The Chinese trade for political reasons.

But the trading hubs are also key. Now that Geneva has become less favourable, Dubai is reaping the benefits. Many commodity traders have a branch there and the trade in Russian oil simply continues. Dubai is a prime place because you can count on the tolerance of the government, which has long been trying to wrest leadership in the global commodities market away from Geneva.

SWI: Is this shift, if seen from a positive perspective, a compliment to the Swiss authorities?

M.P.: No, I tend to believe that the decisive role is played by banks. Commodity finance, i.e., the business of lending for raw materials, is crucial to the industry. The fact that the Swiss banks are no longer involved is not due to the Swiss authorities, but to fear of the US. Trading in oil and gas in Geneva has become less attractive, other commodities are not affected.

SWI: How does the commodities business work in Dubai?

M.P.: They are the same traders as in Geneva. But the state plays a different role. Regulation and trade promotion are combined in a single location, the Dubai Commodities Centre DMCC, a tower where the commodities traders are also based.

SWI: Where does the money come from?

M.P.: BNP Paribas is the major commodity financier in our country. The bank started developing Geneva as a commodities hub with Marc Rich. There are also others in the business in Switzerland, such as the Vaud Cantonal Bank. These banks must be replaced in Dubai.

BNP Paribas could continue to operate outside Switzerland if France tolerates it. But I think that US banks are also involved in Dubai. US authorities are a threat to the Swiss banks, but I don’t think the big American banks have anything to fear. That’s just a guess. There are also banks from the Arab world that operate in Dubai, such as Arab Bank. But I have my doubts as to whether they are sufficiently well capitalised for this business.

More

How Dubai became ‘the new Geneva’ for Russian oil trade

SWI: How can the West improve the impact of sanctions?

M.P.: The sanctions system is not well thought out. Each sanctions list has its own logic. Certain people are protected, others are not. Let me give you an example. There is a Dutch oil trader in Switzerland who is on the UK sanctions list but not on the EU list. Because we implement the EU list and not the UK list, he is protected here.

SWI: Should there be better coordination of the sanctions lists?

M.P.: The way forward would be to coordinate via the G7 task force, and therefore Switzerland should have joined this group. Legally, nothing would have stood in the way of this. The Embargo Act does not force us to adopt the EU sanctions alone. It says that the UN, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and important trading partners must be considered. In addition to the EU, this can also include the US and the UK.

The case of the Dutch oil trader shows that Switzerland is still looking out for its own national interests first. It is unacceptable to be able to trade in Russian oil from Switzerland while sanctions are in place. In my opinion, a joint task force makes sense and it is a mistake not to have a seat on it.

More

The newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) recently aptly described this policy as “muddling through”. I don’t understand Switzerland’s behaviour on this. It would have been an easy win. This way we are acting suspiciously.

SWI: Switzerland has many shipping companies and commodity traders that have their own fleets. What role do these play in the logistics for Russian goods, especially in oil transport?

M.P.: There are many more shipowners in Switzerland than you would think. The oil price cap allows Russian oil to still be traded legally at a reduced price, and this means Switzerland stays in business.

There is one shipowner in Geneva which operates about 30 tankers for Russia. This is a very shady business because the price cap can even be circumvented. As part of the shadow fleet [see infobox below], these ships travel across the oceans uninsured and if something happens, it can lead to enormous problems.

There is also a shipowner from Geneva who is transporting wheat that was stolen [from Ukraine] by the Russians. As far as I know, the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland is conducting proceedings for war crimes. In such serious cases concerning suspected war crimes and money laundering, SECO [State Secretariat for Economic Affairs] has started to pass on cases to the Office of the Attorney General of Switzerland.

The use of shadow tankers is a negative consequence of economic sanctions. They are ships that operate in secret or under false premises. As a rule, the owners are hidden behind a network of companies, there is a serious lack of insurance, and the ships’ routes cannot be tracked because they switch off their transponders and can only be located by radar. The ships typically sail under flags of convenience, meaning they are not registered according to their country of origin, but a country which provides more lenient regulations or lower taxes. Some ships sail under flags that have no controls at all.

The ships are an important factor in the circumvention of economic sanctions. At the same time, they pose a threat to maritime transport and the environment. The tanker Pablo, which exploded and burned out off the coast of Malaysia, made headlines last year. Three crew members died and an oil slick spread across the sea reaching east to the Indonesian island of Batam. The question of who owns the ship is unclear. The Pablo had changed hands three times in the previous three years and was reflagged four times. Most recently, the ship was registered in Gabon

Experts agree that this shadow fleet has expanded dramatically in the wake of the Russian sanctions. Conservative estimates put the number of ships at 600. Pieth, who has written a book about the dark side of shipping and Switzerland’s role in it, cites significantly higher figures. He estimates that 1,000 ships carry Russian oil only, and an additional 500 carry oil from Venezuela.

SWI: Are the authorities in Switzerland better equipped now to recognise violations of sanctions? Is there a recognisable political will to do so?

M.P.: We have to be fair. In the beginning, SECO was caught off guard and had few people who could implement the sanctions. Others who could have helped, such as the canton of Zug, the cantonal commercial register offices and land registries, did not co-operate.

It took time for SECO to set itself up. Of course, the Federal Councillor who was responsible at the time, Guy Parmelin, and his directorate could have more quickly reallocated resources. But the political aspect played a role. Parmelin cannot deny that his party, the Swiss People’s Party, is also close to people who have no interest in enforcing sanctions.

More

Swiss prosecutors reportedly probing Russia sanctions breaches

SWI: Where does SECO stand today?

M.P.: SECO is now positioned reasonably well. But if the sanctions continue, and if the trading hub is also sanctioned, then things will become difficult again.

SWI: Doesn’t this also raise the question of the benefits of such interventions? As you said, the raw materials sector is very agile and is shifting its activities to the Middle East and Asia.

M.P.: What is happening today is that the big commodity companies have offices everywhere. Trafigura, for example, has its headquarters in Singapore but still has a large office in Geneva. Like Dubai, Singapore is about to overtake Geneva in oil and gas, while coffee and cocoa trading remain in Switzerland. In Singapore, you can see and feel what is happening. The shift is almost more noticeable than in Dubai because there is a lot of labour in the region.

SWI: Is this a repeat of what we have already seen with the banks?

M.P.: Something interesting has happened in the financial sector. Singapore has been quick to implement money laundering rules and has done so vigorously. One example is the 1MBD case, one of the biggest corruption cases in the world. Singapore immediately froze suspicious funds and closed down banks, while the financial market supervisory authority in Switzerland procrastinated.

More

Explainer: Why Switzerland remains a ‘big buyer’ of Russian gold

SWI: Is such a turning point in commodity regulation also possible?

M.P.: It is quite possible that Singapore will introduce controls. The state wants to know what’s going on. In Switzerland, the modus operandi for commodities is still laisser faire, with only indirect regulation via the banks.

The question today is which types of business are conducted from where. Perhaps the market will become even more diversified. To put it bluntly, you could say that in Dubai there is a dualistic practice of promotion with supervision. Singapore wants business but also, at some point, information, and in Hong Kong you are bugged. Switzerland more or less lets you do what you want.

SWI: Given their limited impact, are sanctions just moral posturing?

M.P.: I’m reluctant to say that they won’t ultimately work. The effect is limited and the possibilities for circumvention are considerable. That’s also the reason why the Russian economy hasn’t collapsed.

But circumventing the sanctions still costs something. In the long term, they will be very damaging to Russia. Over the next ten years, this will really be felt, for example in the healthcare system and education. And the question will arise as to whether pensions can still be paid.

Edited by Balz Rigendinger/ds

More

Our weekly newsletter on foreign affairs

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.