Learning to speak Swiss

People don’t need to speak languages perfectly to be able to communicate with each other – just one of the encouraging conclusions in a study published on Thursday.

The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) issued its final report on language and language competence in Switzerland, the fruit of five years’ work, under the provocative English title “Do You Speak Swiss?”

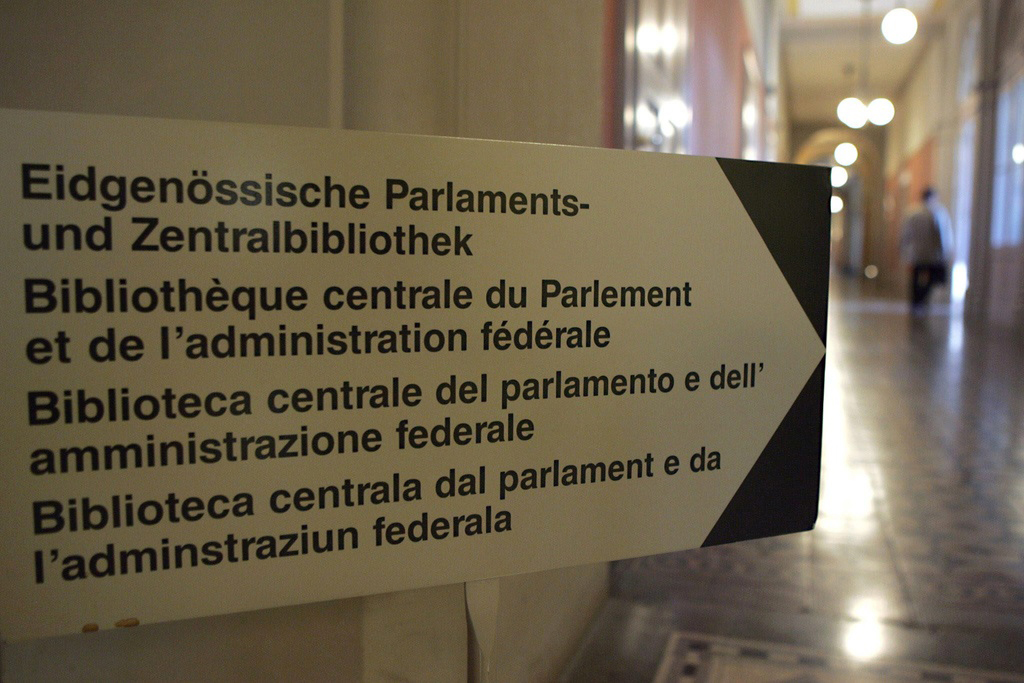

It looks at the complex situation in Switzerland, which has four national languages – German, French, Italian and Romansh – protected by the constitution, and several others spoken by large numbers of more or less recent incomers.

Researchers worked on 26 different projects, covering the areas of language in the law and politics, the linguistic competence of Swiss residents and the promotion of multilingualism in schools.

There is nothing unusual about a country where more than one language is spoken, but the report nevertheless sees Switzerland as a special case.

“What is different about Switzerland is that several languages with very different numbers of speakers are officially recognised as being completely or partially equal,” it says.

“This is still something of an exception and means that multilingualism and the way it deals with minorities are part of Switzerland’s self-image and culture.”

Switzerland is “flexible and pragmatic” in its approach – but times are changing: migration and increasing globalisation pose new challenges. There are more resident speakers of Spanish, Portuguese, English and various Balkan and Turkish languages than there are of Romansh, for example.

Building on multilingualism

“Multilingualism is seen more as a resource than a problem,” Sandro Cattacin of Geneva University told swissinfo.ch. He had conducted research among groups whose members came from different parts of the country: the national U18 football team, the army, and the federal administration.

One of several benefits he cited was the use of different languages to create a group identity.

“Instructors in the military use the different languages to integrate the different parts of Switzerland. For example, one explains something in German. Then he says the same thing more briefly in French – because the French speakers need to understand – and then he will use expressions in Italian for the whole group, like “Forza, ragazzi!” (Go for it, lads!) In that way the whole group is identified with Italian, which is the motivational language.”

“It creates identity by difference, not by behaving as if everyone is the same.”

How to learn a language

The Swiss have a reputation for being good at languages – and indeed, the study found that each speaks on average two foreign languages. But Walter Haas of Fribourg University, who chaired the steering committee of the programme, told swissinfo.ch that there is no such thing as a “gift” for language.

“Everybody can learn a language. The Swiss learn them because they have to,” he said.

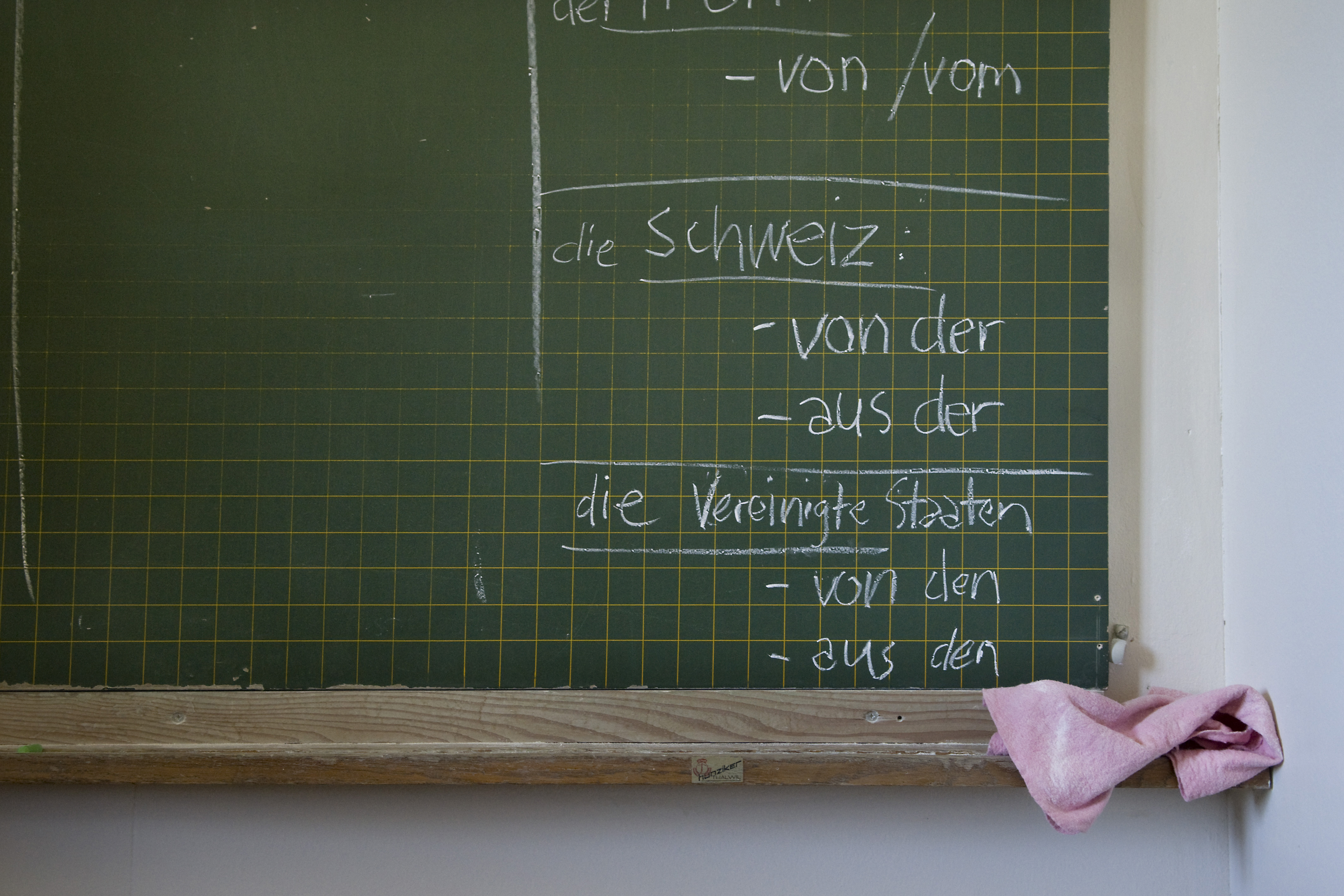

There is good news for those who spent their school language lessons drilling grammar, and ended up unable to produce a single sentence when faced with a real live speaker. The report highlights a significant shift in teaching methods.

“We have learned that people can communicate together without speaking perfectly,” said Haas. “Of course schools have a duty to teach pupils to speak correctly, but it’s all a question of measure.”

A project developed by Bruno Moretti of Bern University takes the bull by the horns. Italian is being edged out as a foreign language, as English becomes more popular and more important.

Italian in a hurry

The thinking is that it’s better for a lot of Swiss to have some grasp of the language, than for just a few to know it well.

He has developed an intensive programme for children aged 12-13, which gives them the ability to communicate in Italian in the space of just a week. Never mind that they will make mistakes: they will be able to express themselves in basic situations.

The standard will be about the same that primary school children have in English after 18 months, he told swissinfo.

By not insisting on total correctness, pilot projects found that many “weaker” students were also able to communicate in Italian at the end of the programme. And as Moretti points out, the mere fact of being able to say something meaningful after a week is motivating in itself.

Although the method was developed in response to the loss of status of Italian in Switzerland, it could be used for other languages as well. Ways of adapting it to teach Switzerland’s fourth language, Romansh, are already being considered.

Seeing the point

Not everyone – even among the Swiss – wants to learn another language.

“If people don’t want to learn, they don’t learn,” said Cattacin. “It’s completely stupid to have policies that say you have to know these languages. What we have to do in Switzerland is to bring people together in projects and give them the possibility to learn together by doing something together.”

While the numerous research projects will help form a basis on which new policies can be developed, no-one pretends that they have reached definitive conclusions.

“The linguistic needs and ideologies of society are constantly changing, and with them so is language itself,” said Haas in his presentation of the final report.

“Investigating language and linguistic relationships is a long term project, and its results are provisional.”

National Research Programmes (NRP) are carried out under the auspices of the Swiss National Science Foundation.

The topics are selected by the Swiss government.

Their purpose ist o provide scientifically substantiated solutions to problems of national importance.

They are usually the fruit of interdisciplinary research.

NRP Language Diversity and Language Skills in Switzerland was commissioned in 2005.

It had a budget of SFr8 million ($8 million).

About 200 researchers worked on 26 projects grouped into three main topics.

The topics were:

Legal requirements and general conditions

Language skills

Language and identity

Percentages of language speakers from the last federal census conducted in 2000

National languages:

German 63.7%

French 20.4%

Italian 6.5%

Romansh 0.5%

Non-national languages:

Serbian and Croatian 1.4%

Albanian 1.3%

Portuguese 1.2%

Spanish 1.1%

English 1.0%

Turkish 0.6%

Tamil 0.3%

Arabic 0.2%

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.