US “u-turn” on detainees wins guarded welcome

The decision to grant detainees in US military custody some protection under the Geneva Conventions is a breakthrough, an international law expert tells swissinfo.

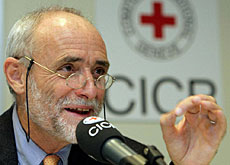

But Andrew Clapham, a professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, warns that other issues regarding their legal situation remain unresolved.

On Tuesday the Pentagon announced that all detainees in US military custody around the world were entitled to protection under Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

The article prohibits violence against detainees, including cruel treatment and torture, and “outrages upon personal dignity” including humiliating and degrading treatment. It also outlaws sentencing or executing prisoners without a fair trial.

For its part, the Swiss foreign ministry said on Wednesday it had “noted with interest” the move and welcomed “this rapid reaction”.

It said in a statement that the development “underlines the primacy of international humanitarian law and, in a difficult context, the universality of human rights”.

The Swiss-run International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) gave a guarded response to the US announcement. Spokeswoman Antonella Notari described it as “an important step taken by the US towards respecting international humanitarian law”.

The move follows a Supreme Court ruling last month that the military tribunals set up by President Bush to try prisoners at Guantanamo Bay were illegal.

The American administration had previously insisted that certain terrorist suspects were not entitled to protection under the Geneva Conventions, which govern treatment of prisoners of war.

swissinfo: How significant a step is this?

Andrew Clapham: I think it sends an important message to all US service people and agents that the United States is bound by the Geneva Conventions and that everybody has to be treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. That was not the message that was being sent out before, and we know that some of the mistreatment took place against that background.

Hopefully people will now think twice before mistreating someone. After a little research they will also discover that violating Common Article 3 gives rise to personal responsibility for a war crime.

swissinfo: Does this “u-turn” represent a victory for the ICRC or has the Bush administration merely bowed to the Supreme Court?

A.C.: I think it’s a bit of both. The ICRC, Mary Robinson [former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights] and various non-governmental organisations have all been arguing that the Geneva Conventions apply in this context.

Of course, it’s been precipitated by the Supreme Court decision, but it wasn’t such a big step to take in the sense that everybody had been arguing that the Geneva Conventions apply.

swissinfo: But the Pentagon ruling only covers those held by the military and not by the CIA.

A.C.: The rule is that the “party to the conflict” is bound by Common Article 3, not just the US Defense Department. And the “party to the conflict” means the United States. So the idea that CIA-held prisoners are not covered by this doesn’t hold much water.

swissinfo: The Pentagon denies that this is a policy reversal, saying that detainees have always been treated “humanely”. Are we likely to see any concrete changes in the treatment of detainees? And how can this be monitored?

A.C.: The ICRC visits detainees, so they are being monitored. Also from time to time people are released and then they tell their stories as to how they were treated. But it’s very difficult to say what will happen immediately.

A lot of this is psychological. But it does send a strong message, and there won’t be this argument anymore that [the US] is not bound to treat these people humanely because they’re not covered by the Geneva Conventions. Now it’s clear that they are.

swissinfo: The door seems to have been left open for special military tribunals to try detainees. Are these likely to comply with Common Article 3?

A.C.: The problem we have is that Common Article 3 refers to “all the judicial guarantees recognised as indispensable by civilised peoples”, and it’s never really been tested as to what that means.

But the real issue is not necessarily the military tribunals, it’s the 90 per cent of people who are not going to be tried by them. I think this will be the new legal battleground. When are they going to be released and when are they going to have their day in court to determine whether they should be released or detained indefinitely? That issue hasn’t been resolved either by the application of Common Article 3 or by the Supreme Court.

swissinfo-interview: Adam Beaumont in Geneva

The Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols, of which Switzerland is the depositary state, form the backbone of international humanitarian law.

The conventions define the treatment of civilians and combatants in times of war and occupation.

Henry Dunant, founder of the Swiss-run International Committee of the Red Cross, initiated the first convention in 1864.

The four conventions were revised and extended in 1949 to cover armed forces on land and sea, prisoners of war and civilians.

Andrew Clapham is a professor of public international law at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva.

He is also director designate of the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, which is due to open in October 2007.

Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions prohibits violence against detainees, including cruel treatment and torture, and “outrages upon personal dignity” including humiliating and degrading treatment. It also outlaws sentencing or executing prisoners without a fair trial.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.