Diplomacy and science working hand in hand

Switzerland is a strong advocate of “science diplomacy”, which it considers essential to meet global challenges such as the coronavirus pandemic. Alexandre Fasel, Switzerland's first special representative for science diplomacy in Geneva, explains.

When scientists discover something, they don’t always know what its practical use is going to be, nor do they know the consequences that their discovery might have on society. The same goes for engineers who develop the associated technology. For example, when Otto Hann and Lise Meitner discovered nuclear fission in Berlin in 1938, they had no idea that it would lead to the atomic bomb a few years later.

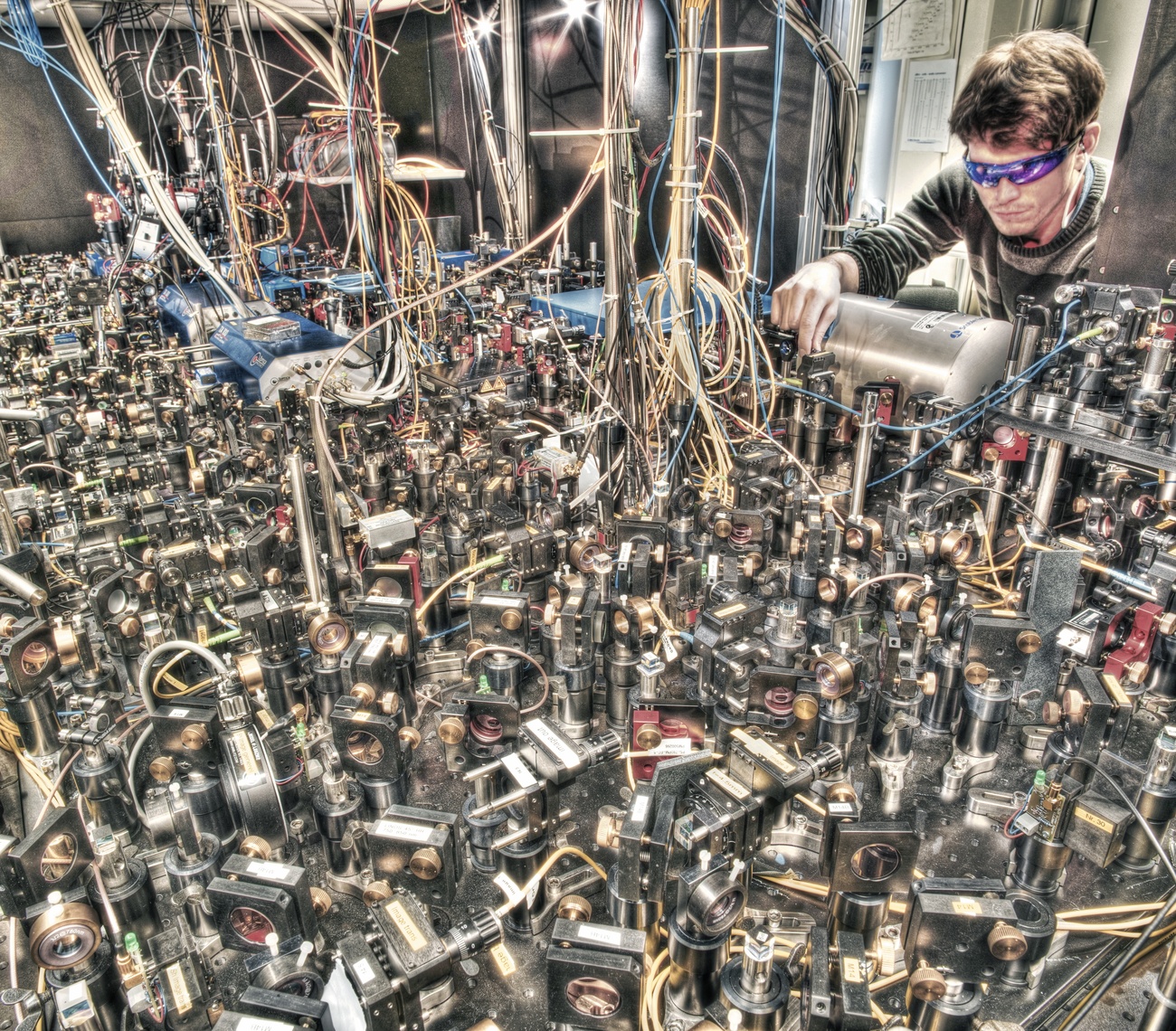

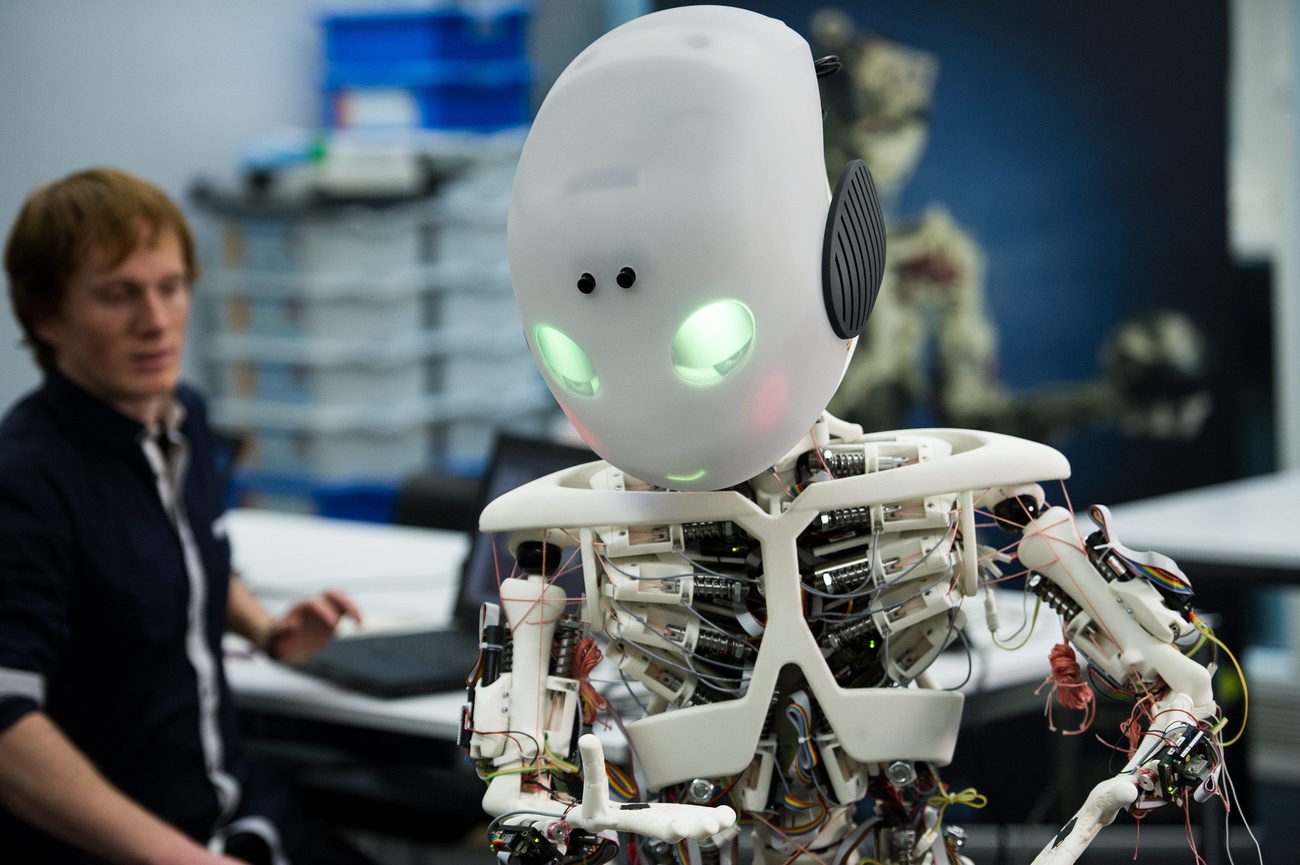

For their part, diplomats who must solve the world’s problems do not always know what important developments they should bet on to solve the challenges of tomorrow. Technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and nanoscience are evolving more quickly than ever. Given this fact, Switzerland is backing an innovative approach to tackle the challenges of the world: it is supporting a new platform, the Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA – see box below), which is holding its first summit in Geneva from October 7 to 9.

SWI swissinfo.ch: How is science used in diplomatic negotiations?

Alexandre Fasel: Scientific diplomacy encompasses extremely varied activities which we can divide into three key areas: diplomacy for science; science for diplomacy; and science in diplomacy.

Diplomacy for science is when diplomacy is needed so that science can be carried out – so that international scientific collaboration can take place. One example is the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). A lot of diplomatic work was necessary to bring countries together around this idea, to establish a convention or to find funding.

Then there is science for diplomacy. The Transnational Red Sea Center is a research project focusing on the unique corals of the Red Sea, and via which we undertake diplomacy through science. The ten states bordering the Red Sea, which do not always have excellent diplomatic relations, have a common interest in this scientific project. It creates the conditions for countries which normally do not favour cooperation to work together and build mutual trust. This then facilitates discussion of other questions, of a less scientific and more diplomatic nature.

More

Swiss scientific diplomacy sets sail to save corals

Finally, science in diplomacy is when science becomes entirely instrumental in diplomacy. A good example is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Pooling existing scientific knowledge of climate change makes it possible to offer a vision based on data and which is therefore accepted by the international community. This vision is scientifically stable and solid, which helps to define the object of the discussion and the challenges that diplomacy must face. Without the IPCC, the Paris Climate Agreement would not have seen the light of day.

SWI: Why is this so important for Switzerland?

A.F.: Because as the host state of International Geneva we have an increased responsibility: we must commit ourselves relentlessly so that the global governance system is effective, strong and solid. This adds to our scientific weight. Switzerland, in this context, is a great nation, with substantial resources and networks all over the world allowing us to contribute to this anticipatory effort. It is therefore a double motivation that drives us to invest in science diplomacy. The foundation of GESDA, requested by the Federal Council and the Geneva authorities, is a major, concrete achievement of this policy.

>> Alexandre Fasel explains how rapidly evolving scientific discoveries will change the face of the world:

SWI: One of the hottest topics in international diplomacy is the Covid-19 pandemic. How is science diplomacy used to solve this challenge?

A.F.: In the context of the pandemic, the vaccine is an incredible victory for science. No one believed that it would be possible to develop effective and safe vaccines in such a short time. Science diplomacy contributed to this success, by facilitating collaboration between researchers, producers and distributors. Conversely, the Covax programme, the international instrument aimed at making vaccines available to the greatest number of people, has not yet borne the fruits that we hoped for. This highlights the difficulty of making scientific breakthroughs available to the people who need them.

SWI: Can diplomacy really be based on science?

A.F.: This is the whole debate around evidence-based policy. Science, and the strength of scientific knowledge, must be the basis of the debate. But then, this dimension has to be integrated into the diplomatic discussions between the actors of world governance. These actors have national interests, geopolitical positions and other motivations that condition state conduct. It is a question of ensuring that the basis of their conduct and their decisions are firmly anchored, in order to rally the various actors around a consensus.

The Geneva Science and Diplomacy Anticipator (GESDA), a relatively new start-up backed by the Swiss government and Geneva authorities, will hold its first summit on October 7-9. Its line-up of speakers is impressive, as are the issues to be discussed. These include: de-carbonising the planet, negotiating the boundaries of genetic science, artificial intelligence and learning from Covid-19.

Diplomats and scientists often live in different worlds and don’t have open access to each other’s community. GESDA says it wants to break down these silos, get them talking and thinking together, along with academics, civil society and business. Through these consultations, it aims to “anticipate” important scientific breakthroughs in the next five, 10 and 25 years, then identify what might be needed to go with them in terms of governance, such as, for example, an ethical framework. The third phase will be raising funding to implement “solutions”.

“The idea is to come out of this summit with very concrete views on some of the topics and what to do next in order to address the issues that we’ve identified,” says GESDA’s Science Communication and Outreach director Olivier Dessibourg.

GESDA was officially launched in September 2019External link. Its founders are the Swiss government and the canton and city of Geneva, which together provided CHF3.6 million ($3,9 million) for the three-year pilot phase to the end of August 2022 (CHF3 million from the Swiss federal government and CHF300,000 each from the canton and city of Geneva). GESDA has also raised CHF6.4 million from private donations.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!