Killer robots: ‘do something’ or ‘do nothing’?

Countries are split over whether to agree strict rules on killer robots – lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs) – and campaigners have serious doubts that the United Nations in Geneva is the best place to deal with the issue.

Human Rights Watch’s Mary WarehamExternal link is fuming after week-long talks at the UN in Geneva on what to do about killer robots.

“We’re pretty appalled,” says the coordinator of the Campaign to Stop Killer RobotsExternal link. “Where is the diplomacy, responsibility and leadership from the big states?” she told swissinfo.ch on Friday.

The result, she says, is extremely frustrating.

“The UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW)External link was a way of placating NGOs into thinking that governments were taking meaningful action on LAWs. Now all they’re talking about is possible non-binding principles that I can foresee government delegates will negotiate for another year or two.”

Since 2014, diplomats, disarmament experts and campaigners have met six times in Geneva within the multilateral CCW framework to discuss the multiple ethical, legal, operational, security and technical challenges of killer robots.

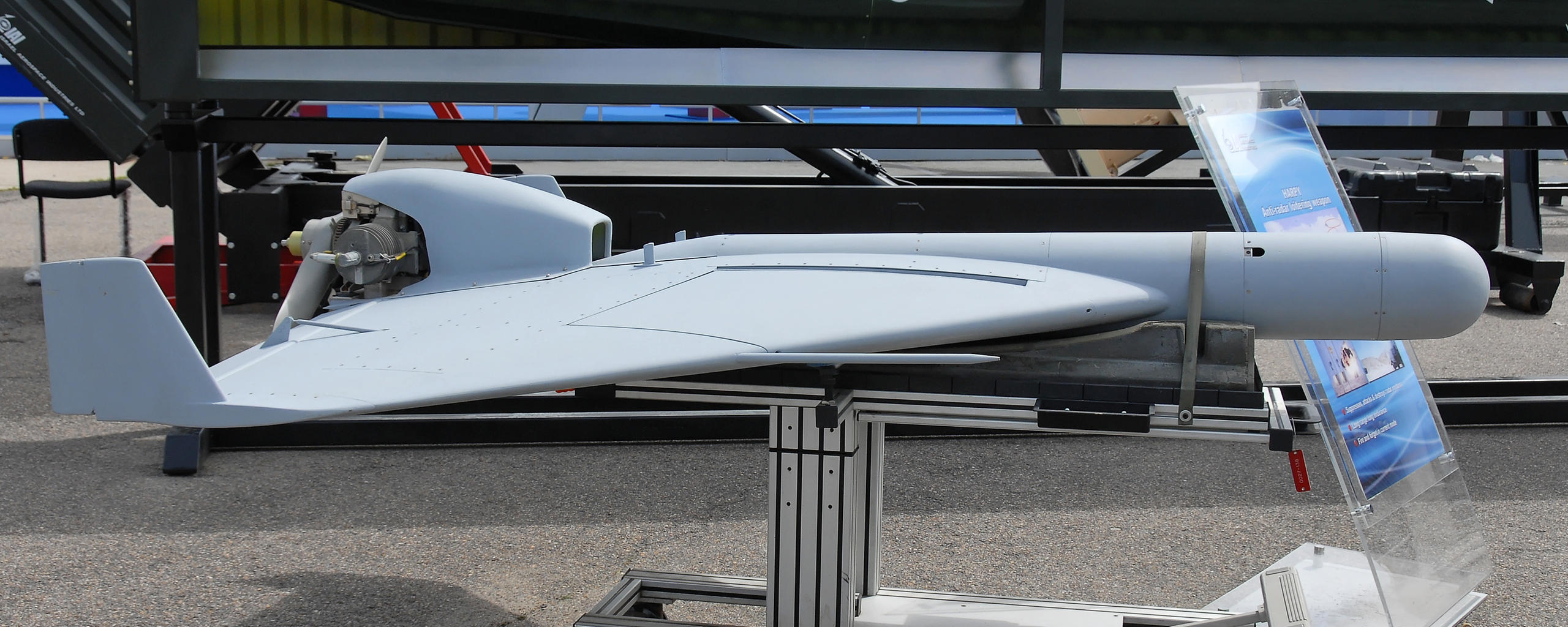

Fully autonomous weapons do not yet exist, but campaigners say they could be deployed in battle in just a few years given rapid advances and spending on artificial intelligence and other technologies.

Over 380 partly autonomous weapon and military robotics systems – such as AI-powered tanks, planes and ships – have reportedly been deployed or are under development in 12 states, including China, France, Israel, Britain, Russia and the United States.

On the arms control front, several countries, like Japan this week, have committed to not acquiring or developing LAWs. And a majority of states have expressed support for some kind of new international law containing prohibitions and regulations of LAWs.

Twenty-eight countries – and the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots – want a pre-emptive global ban treaty on the development, possession and use of such future weapons. Others advocate strict regulation to affirm the principle of “meaningful human control” over critical functions.

Critics say LAWS raise huge ethical questions on delegating lethal decisions to machines and on accountability. They fear that the increasingly autonomous drones, missile defence systems and tanks could turn rogue in a cyber-attack or malfunction.

But there is strong opposition to a treaty from a handful of countries, including the US, Russia, Israel and South Korea. Supporters argue that LAWS will make war more humane. They will be more accurate in choosing and eliminating targets, not give way to human emotions such as fear or vengeance, and will limit civilian deaths, say those in favour.

“There’s a real divide here between the ‘do-something’ states and the ‘do-nothings’,” says Wareham. “I don’t think the public will be satisfied if the end result here at the CCW is to form a committee or to draft a weak declaration with no legal impact.”

A recent Ipsos public survey published in January found that 61% of respondents in 26 countries opposed the use of LAWs.

For campaigners, the endless talk and obstruction in the CCW by a small group of “militarily significant states” has gone on long enough. The coalition of 100 NGOs from 54 countries plans to take their fight to the UN General Assembly in New York in September, with support from UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

The campaigners intend to push for countries to agree by November to a mandate for negotiations on a global ban treaty, rather than a non-binding declaration. If this fails, other paths could be explored, they say, such as an independent process outside the UN similar to the Ottawa Process on landmines or the Oslo Process on cluster munitions.

Swiss position on killer robots

Switzerland is sceptical about a preventive ban at this stage, but it backs practical, and if necessary, regulatory measures to prevent any use of LAWS that would violate international law. In 2017, it tabled a working paper entitled a “Compliance-based approach to Autonomous Weapons SystemExternal link” that reaffirms the importance of international law.

In 2017, the Swiss Federal Council (executive body) rejectedExternal link calls for an international ban on LAWs. It said it had “reservations” and that clarification was first needed regarding “desirable”, “acceptable” and “unacceptable” autonomy of weapons systems.

Swiss ambassador to the Conference on Disarmament, Sabrina Dallafior, told the Le Temps newspaper on Thursday: “The strict prohibition of all autonomous lethal weapon systems can be an attractive prospect at first glance. But right now, we do not know exactly what should be prohibited. There is a danger that we could also ban systems that could be useful, which help prevent collateral damage, for example.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.